The sports industry has been resilient in the face of broader economic uncertainty that’s dampening the overall M&A market, something experts attribute to the sector’s unique stability, an influx of private capital, consistent revenue streams, and fan loyalty.

Experts expected a surge in M&A activity this year under President Donald Trump, thanks in part to the perception that he would be more business-friendly than the Biden Administration, which took an aggressive approach to regulation.

But through the first quarter of 2025, dealmaking was down. There were roughly 7,551 global M&A deals announced through the end of March, significantly less than the 10,176 during the same time period last year, according to data from Dealogic. In fact, there were at least 10,000 M&A deals announced in the first quarter in each of the prior 10 years, Dealogic data shows.

The unexpected M&A slowdown can be attributed to multiple factors, including Trump’s fluctuating tariff policies, which have disrupted the global markets and worried business owners, including small sports retailers that fear they won’t be able to foot potentially massive tariff bills. Trump’s 90-day pause on tariffs, except those levied against China, isn’t exactly quelling fears. Companies have no idea how to project what might happen three months from now, when those 90 days are up.

“Uncertainty is the enemy of M&A,” Alex Michael, a managing director at investment and merchant bank LionTree, tells Front Office Sports. “People want strong footing before they jump at things.”

Sports investors are not showing the same hesitancy to do deals—from pro franchise sales to smaller corporate transactions in the space.

Examples from 2025 on the pro sports front include the Boston Celtics record $6.1 billion sale, the San Francisco Giants’ sale of a 10% stake to private equity firm Sixth Street, and the National Women’s Soccer League’s foray into Denver, a deal which carried a record-breaking expansion fee of $110 million.

In the realm of corporate M&A, early 2025 has featured a range of transactions, from the Ardenton Capital’s sale of LED video scoreboard maker OES, whose products are used by leagues including the NHL, NBA and NFL, to Interactive Strength’s acquisition of Wattbike, an indoor training bike company that says its bikes are used by “every single Premier League team.”

Other recent sports sector transactions include one announced Thursday, under which Topgolf Callaway Brands is selling its Jack Wolfskin business to China’s Anta Sports for $290 million, as well as KKR-backed PlayOn’s deal to pick up high school sports information provider MaxPreps.

“For the time being, there are no signs it’s going to abate,” Michael tells FOS. “If there’s an attractive team for sale, an attractive sports tech play for sale, certainly in areas like youth sports and college sports, these things are going to find a home.”

Sports As ‘Safe Harbor’

Something a number of the corporate sports sector deals have in common is that there is a private equity firm involved. Private equity firms often view volatility as opportunity. The COVID-19 pandemic is a prime example: Firms tried to take advantage of the disruption then, and companies owned by private equity firms outperformed non-sponsored peers during that period, according to a report in the Journal of Corporate Finance.

“This is a great time to be investing capital, generally,” Mark Affolter, a partner and co-head of sports, media, and entertainment at private equity giant Ares Management, tells FOS.

Ares is a major player in the field of sports dealmaking. The firm last year acquired a 10% stake in the Miami Dolphins. It also owns a significant equity stake in MLS team Inter Miami, which has global icon Lionel Messi on its roster, and is invested in League One Volleyball, among other sports holdings.

“As an investor, we believe there’s a bit of a safe harbor associated with this asset class,” Affolter says.

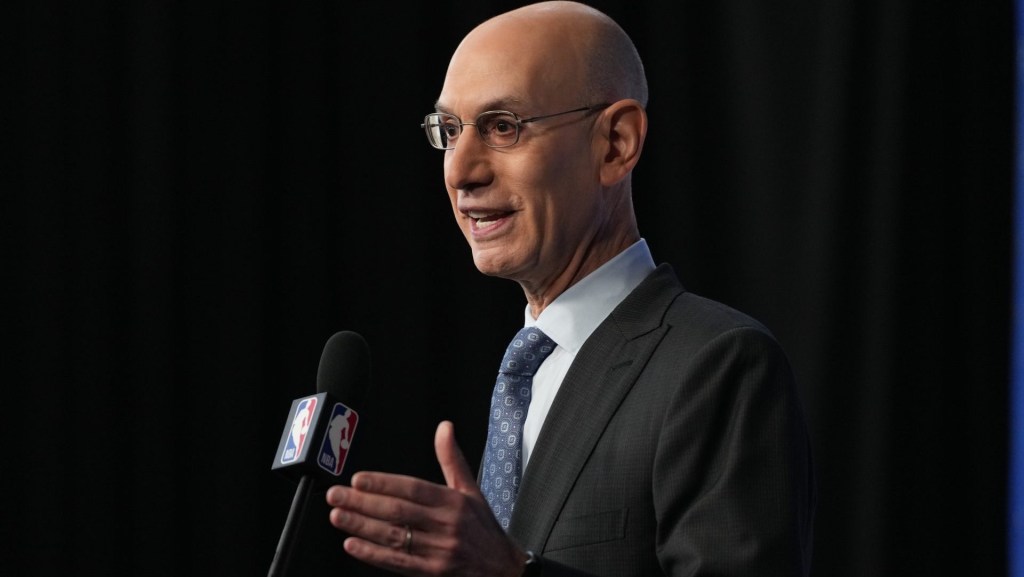

Why? One major factor is the rising value of media-rights deals for pro leagues, which typically span long time periods and therefore represent a guaranteed revenue stream for many years. As examples, the NBA last summer reached an 11-year, $77 billion media-rights deal, while the NFL is reportedly planning to opt out of its 11-year, $111 billion media-rights deal because it feels it could do even better.

The rise of streamers in sports, with their deep pockets and wide-ranging reach, has been a game-changer in the media-rights space. Streamers are projected to spend $12.5 billion on global sports rights this year, claiming 20% of the overall market, according to a February report from market research firm Ampere Analysis. That’s a significant jump from just 8% in 2021—a sign of how quickly their presence in the sports rights arena is expanding. The NFL recently announced a Christmas Day tripleheader that will feature two games on Netflix and one on Amazon Prime Video, and Netflix set a streaming record last year with its bout between Mike Tyson and Jake Paul.

But Affolter says there’s something even simpler that is vital to understanding why sports doesn’t necessarily suffer when the stock market stumbles.

“It’s the value that individuals ascribe to unique content like sports,” he tells FOS. “The fan dynamic. If anything, that’s probably been amplified over the last five years coming out of COVID.”

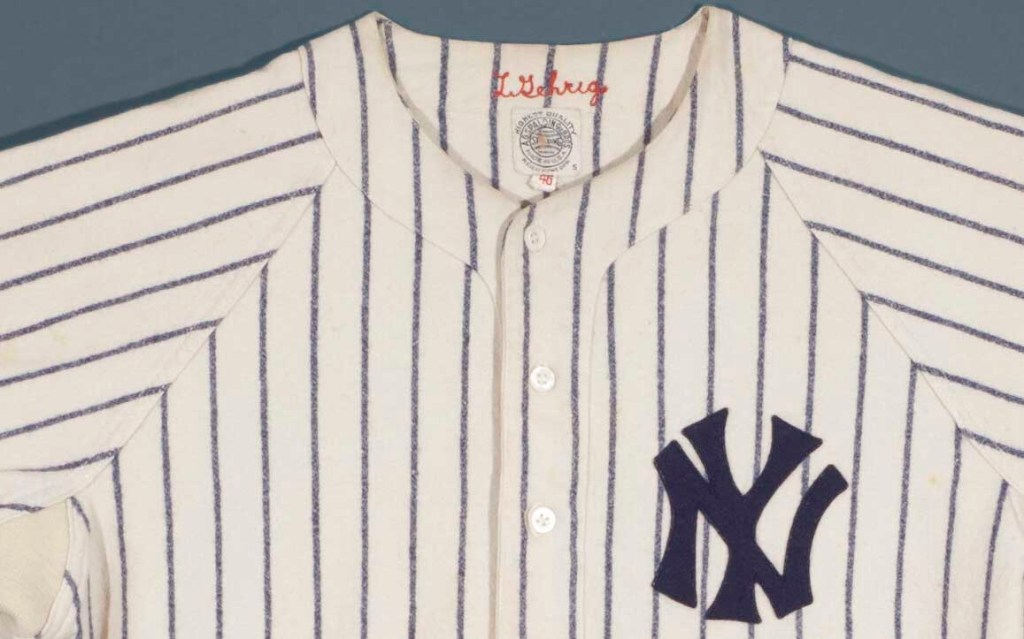

For at least the next half-decade, sports should continue to be a powerhouse with regard to dealmaking. The appetite is there, more players are entering the field, and the fact is that, as a sector, sports is an ecosystem that feeds itself. Pro sports franchise valuations are only climbing higher, with each deal breaking the dollar-value record set by the last. Those teams, and the leagues in which they play, need to keep finding ways to add value for fan bases with increasingly shorter attention spans.

At the moment, it feels like the business of sports is rocketing into the stratosphere, and the money is only going up. ESPN recently walked away from a deal worth $550 million per year with MLB that was supposed to last through the 2028 season, and it seems like MLB is increasingly looking to spread the wealth across multiple broadcast partners.

Of course, the good times can’t last forever. There’s no guarantee the current trends in sports will endure over the long haul.

“We’ll have some real tests, especially when it comes to media rights, in five to seven years,” says LionTree’s Michael, who leads the firm’s work in the sports industry. “You can look ahead and see the dominoes around streaming and cable broadcasting. There are enough pockets of capital in the landscape where you typically have seven or eight people vying for rights when new media deals come up. If that shrinks to four or five people at the table, or two or three, the dynamics could shift.”