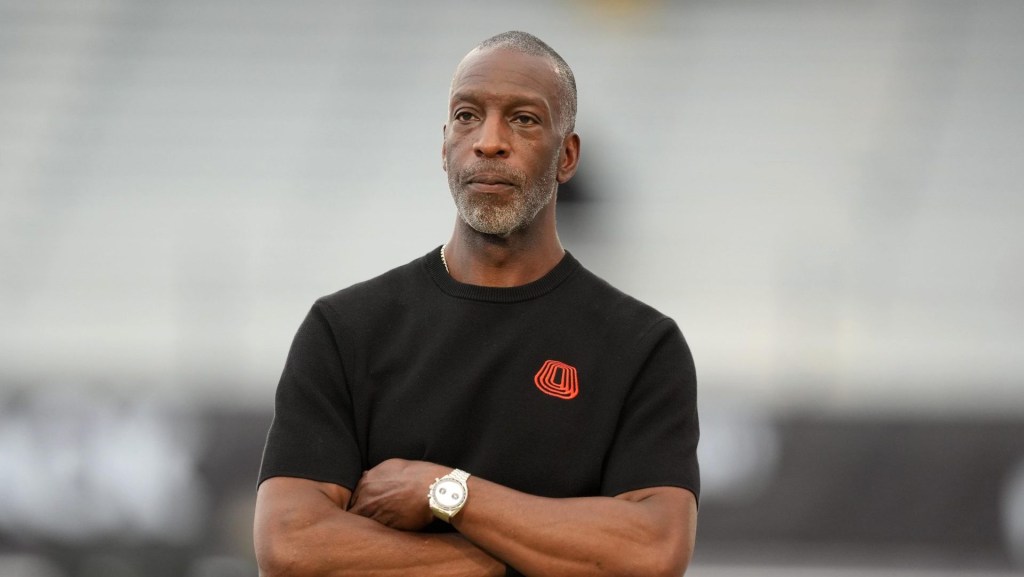

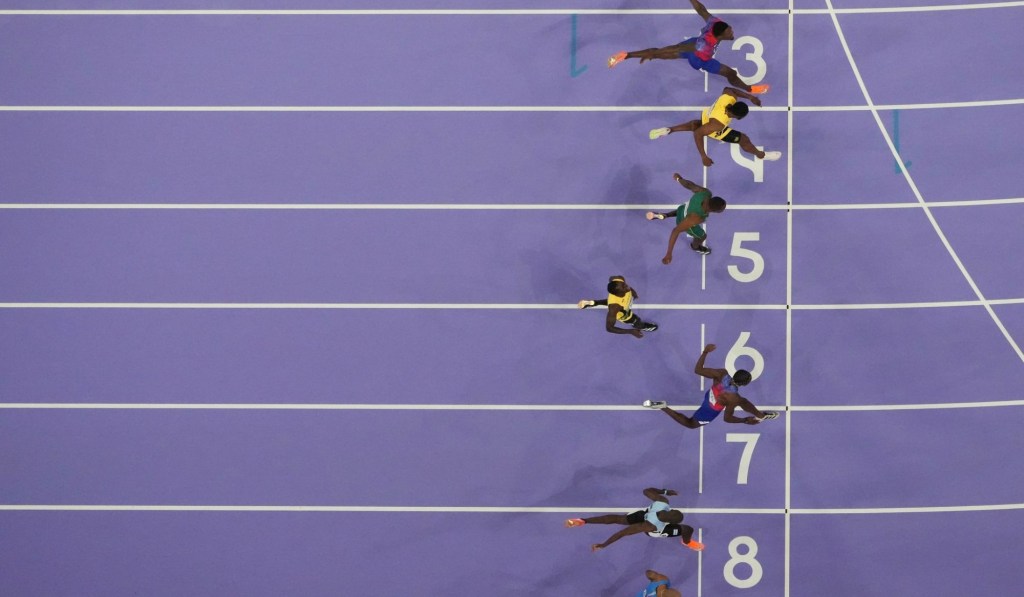

Jerry Solomon is married to an Olympian, but it took another athlete to open his eyes to his next big venture. The sports agent – and husband to former Olympic figure skater Nancy Kerrigan – was in Rio during the 2016 Summer Olympics to support his client, judo wrestler, and gold-medalist Kayla Harrison.

While in Brazil, Solomon paid close attention to coverage between the male and female athletes. What he saw gave him the inspiration behind an event meant to change this narrative: The Aurora Games.

“In 2016, there were more women than men on the U.S. Olympic team,” Solomon said. “I thought they were doing better, but they weren’t getting the same amount of coverage. With that, I thought, ‘well, we should start something that gives them their own platform, totally independent of the men, where the spotlight can really be on women in sports.’ That’s really where the whole idea [for the Aurora Games] emanated from.”

Fast forward to 2019, and the Aurora Games made its inaugural debut Aug. 20 to 25 at the Times Union Center in Albany, New York. According to Solomon, the event is a multi-sport occasion meant to provide a platform for female athletes. When looking where to host it, Solomon always envisioned the East Coast. Little did he know that New York’s state capital would be the most enticing option.

Before the Aurora Games, the Times Union Center recently merged with property management firm SMG. After the merger, a $25 million renovation project went into the venue – which included the addition of a convention center – that was completed last May. Bob Belber, SMG general manager of the Times Union Center, is long-time friends with Solomon and insisted that he consider having the Aurora Games in Albany.

“It had all the elements that we were looking for and I knew that they could do the changeovers from one sport to the next, which was not going to be easy,” said Solomon. “We got into discussions with the city and the state and the county and had a lot of support [for hosting the event in Albany].”

When Aug. 20 finally arrived, some of the world’s biggest female athletes descended on Albany for the week. With honorary captains such as Nadia Comaneci and Jackie Joyner-Kersee, 109 athletes from 25 countries were represented at the Aurora Games. It included American talents such as women’s hockey player Amanda Pelkey and gymnast Katelyn Ohashi. It also featured Grand Slam tennis stars such as Victoria Azarenka (Belarus), Garbiñe Muguruza (Spain), and Monica Puig, 2016 Olympic Gold Medalist – Women’s Singles (Puerto Rico).

Despite the star power that sports like gymnastics, hockey and tennis boasted, Solomon was disappointed with the turnout. According to him, attendance was lower than expected; for the six-day spectacle, 20,453 people showed up – an average of 3,404 per session. Even though his expectations weren’t met there, he believes that a good foundation has been set for future Aurora Games.

“My expectations on the attendance side were tough to have – frankly because it was a first-time [event] in a new location,” said Solomon. “No history to it at all and it was really hard to gauge as to what to expect from an attendance standpoint. I think that having said that, I was a little disappointed in the live crowd – but I think it’s a building scenario, not meaning a growth scenario. I think we have established in a lot of ways the Aurora Games name brand in a very short period of time.”

Going forward, Solomon knows that changes need to be made for the Aurora Games to succeed. One of those updates, he hopes, is in the venue. Given the Times Union Center’s indoor atmosphere, there weren’t as many opportunities for outdoor events. With Aurora Games returning to the Capital Region in 2021 and 2023, Solomon aims to host outdoor sports – like soccer, lacrosse, and rugby – at other outdoor facilities.

With social media promotion largely on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, he hopes to better promote and distribute the event to the masses. This year, the Aurora Games were featured on ESPN, ESPN3, ESPN International, Eurosport, and Canadian-based CBC Television among others. Solomon could not comment on the ratings and viewership of the event – which were broadcast live every day during its duration.

Although much has been said about Solomon’s mission, there is still skepticism with it. A source who attended the Aurora Games says that its marketing appeared localized to the Greater Albany area. If it wants to be anywhere as impactful as the FIFA World Cup – which every four years attracts fans worldwide – this source says it needs to appeal to everyone – not just the locals.

READ MORE: Women In Sports Roundtable: Big Sky Athletic Directors

After learning about the Aurora Games through a peer, the source said, they loved it for what it stood for. To them, it provided extensive coverage to female athletes who normally don’t receive their due, and be a catalyst for changing this disproportion.

To achieve this, the source believes that the event’s content should focus deeply on the athletes. One push that the WNBA has made recently is telling the story of its players and how they achieved their dreams – like 2019 All-Star Game MVP Erica Wheeler. Although the Aurora Games produced memorable moments – with four plays from the event making ESPNW’s weekly top 10 list – it needs to capitalize on them through social media. Otherwise, the source thinks that it runs the risk of being unoriginal.

Journalist Erica Ayala had similar thoughts regarding the Aurora Games’ shortcomings. As a writer for The Athletic, Ayala attended the event as a media member, with the fact that something of this magnitude was happening in women’s sports sparking her interest.

However, once she arrived at the Times Union Center, that enthusiasm melted into worry.

READ MORE: Tennis’s Next Big Star? Call Her Coco

At the Aurora Games, Ayala noted the venue’s poor conditions – despite the $25 million renovation project. When covering the women’s basketball event, she noticed condensation around the court – creating unusually difficult conditions for both players and the media. Instead of a seamless transition from hardwood to ice for basketball and ice hockey/skating events, she felt it was unnecessarily challenging – and affected their preparation.

Similar to others at the event, Ayala felt a disconnect between spectators and the general public. Her impression was that only select media and people knew about the Aurora Games. With poor marketing outreach and underwhelming facility conditions, she believes that what could’ve been a banner moment for women’s sports instead brought more questions than proclamations.

“[The media members] knew that there was this thing called the Aurora Games, but it was a little bit difficult,” said Ayala. “You had to do your due diligence to find out what the Aurora Games was. I think that there was a missed opportunity to have the athletes truly be prepared to be ambassadors for the [Aurora] Games and use their social media and different outlets and word of mouth that way to promote the game.”

Solomon recognized that the first edition of the Aurora Games was not perfect, but believes that its launch is a step in the right direction for women’s sports.

“Is there room for improvement? Of course,” said Solomon. “I think that the athletes recognize that this was an event that was put together with the athletes in mind first, second and third. I think we delivered on that – in a fairly strong way.”

“The biggest takeaway is that we saw multiple generations of female athletes all coming together from all over the world, in one location, to celebrate the prowess and the entertainment value and the celebrity of the athletes and the power and finesse of their athletic achievements,” said Solomon. “We’ve brought a lot of focus to that. That’s got to be a positive in the overall scheme of things – and certainly lay the groundwork for doing a lot more of that in the future.”