Attendance was lackluster, awareness waning and revenue dwindling for the College Football Hall of Fame in South Bend, Ind. But a move to a major market and several key strategy shifts sparked a much-needed resurgence for the Hall as both a shrine to the sport’s storied history and an in-demand event venue.

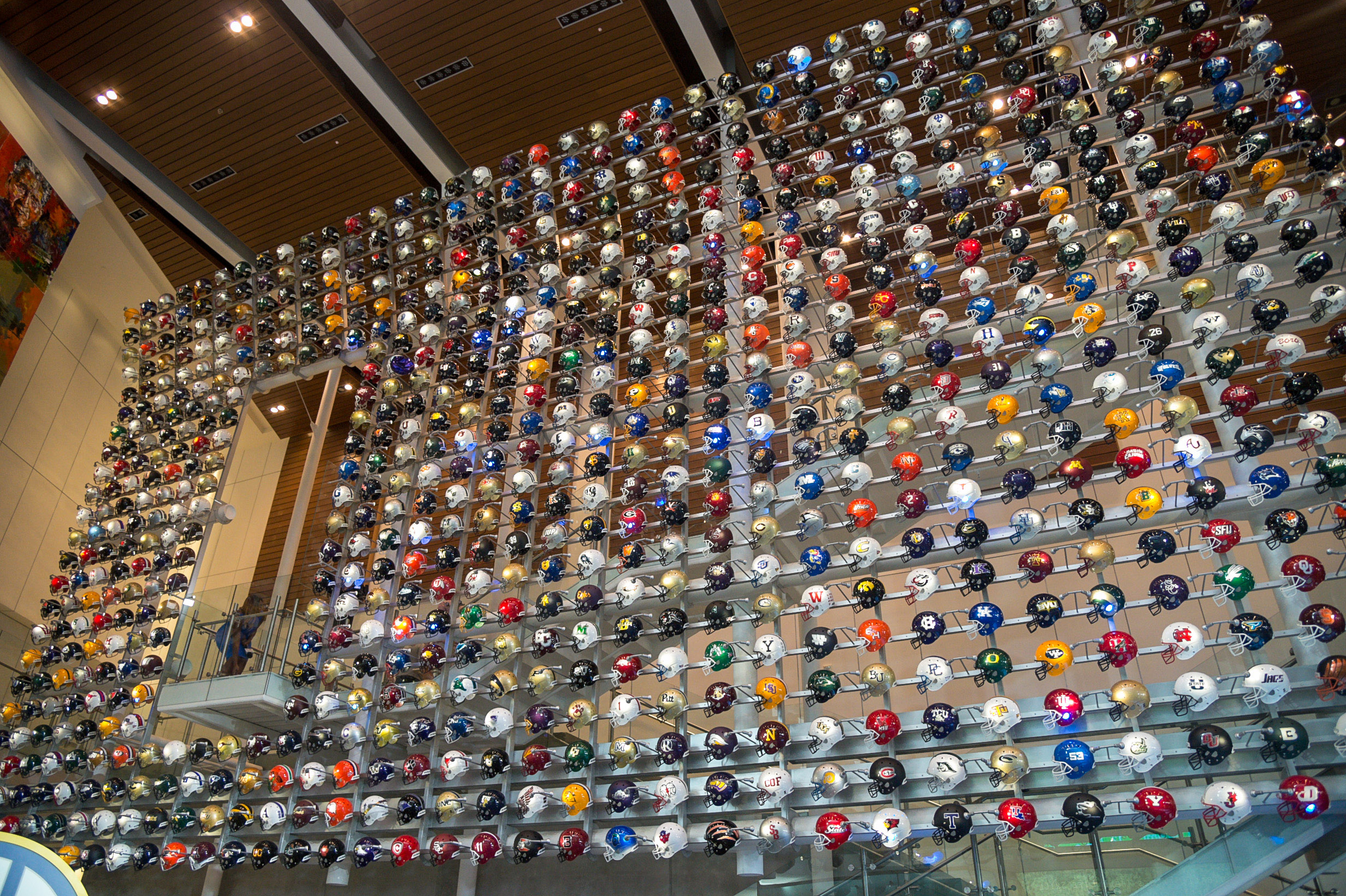

Sitting steps away from Mercedes-Benz Stadium and the iconic Centennial Olympic Park in the heart of downtown Atlanta, the building and the experiences the new Chick-Fil-A College Football Hall of Fame houses were designed to reinvigorate the 42-year-old Hall, which found its first home in Kings Mills, Ohio in 1978.

A non-profit, Atlanta Hall Management, was created specifically to build the new Hall and manage its day to day operations upon its reopening in 2014. The group decided to outfit the $68.5 million, 95,000 square foot space with RFID technology to customize and modernize the experience for each individual coming through the doors of the new building.

The location was chosen so the museum could capitalize on the swarms of fans who visit the area annually for some of the sports world’s biggest events. And as an increasing number of marquee sporting events have been hosted in Atlanta in recent years, and 2019 in particular, the Hall has found its footing.

When the Patriots defeated the Rams for their sixth Super Bowl victory last February in Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the local economy got a $400 million boost. The College Football Hall of Fame, although not NFL affiliated, benefitted from that same surge – hosting nine separate events in a four-day span during Super Bowl week and seeing spikes in attendance surrounding each one.

The Falcons’ home field then received ardent college fans in December for the Peach Bowl, a College Football Playoff semifinal game, and the Hall saw consecutive days of record-breaking paid attendance, welcoming 10,000 fans.

“We do capitalize on peak times and peak opportunities to host events,” Kimberly Beaudin, the Hall’s senior vice president of marketing and sales, said. “I think any sporting event going on in the area will drive attendance as we saw with something like [the Super Bowl] but it doesn’t drive it the way specific college events do.”

Beaudin attributes the boost to the specific promotions they did around the event and to both the Peach Bowl’s own record-setting attendance and its role as a semifinal game this season. It was incentive enough, she says, for LSU fans to return to Atlanta just three weeks after the team’s SEC championship win in the city and for Oklahomans to trek to the team’s first-ever game in the state of Georgia.

With ticket prices starting at $17.99, the Hall’s attendance revenue for those two days alone was more than $180,000. For a space that was struggling to get anyone through the door just a few years ago, “that was great,” Beaudin said.

They also saw an influx of people and partners around the events the Hall hosted, which resulted in additional dollars.

READ MORE: NHL Bankrolls College Hockey Expansion As Youth Game Explodes

Nearby college and professional sporting events do more than drive attendance and provide opportunities to host events and activations. The proximity puts the Hall in a unique position at the intersection of major sporting moments and key fan bases as well as at the epicenter of college football, which adds appeal for sponsors.

Revenue earnings have been complemented by a steady stream of partnership dollars coming from big brands, including naming-sponsor Chick-Fil-A, Coca-Cola, The Home Depot, Kia, Georgia-Pacific, Goodyear, Under Armour and the Peach Bowl itself, among others. Brands see potential in the reborn Hall and are drawn to the opportunity it presents.

“We were the first founding partner to put money into the hole because we believe in college football, bottom line,” David Epps, COO and vice president or marketing for the Peach Bowl, said. “We believe [in] what it means culturally to the fans. Especially in the market that we are in. We knew how important college football had always been here and would continue to be. With a city the size of Atlanta, with the number of visitors that come in here and with a number of locals who have college football ties, we just felt like there wasn’t going to be a better city in America for the Hall of Fame to call home than Atlanta.”

Since the Hall reopened, Atlanta has hosted two College Football Playoff semifinal games, the SEC championship, the CFP National Championship in 2017, the Celebration Bowl – played between the champions of the MEAC and the SWAC, the two prominent conferences of historically black colleges and universities – along with the 2018 March Madness South Regional and a Super Bowl.

And this spring, when the Final Four floods Atlanta’s hotels and hungry March Madness fans feast on bar food and sip on sweet tea, the goal is to do the same: specifically cater to the college fans coming to town and capitalize on the NCAA Tournament’s presence.

Beaudin says the Hall hopes to host three to four major events for Final Four from the corporate side without taking away from availability or access to the venue for visiting fans. Maximizing both attendance and events is a crucial balance the Hall must maintain around big games.

“We’ve become very comfortable with what our financial norm is without these marquee events but then we’re leveraging those events to push us over the top,” Beaudin said.

For an event like the Final Four, which attracts college fans that are not football-specific, the Hall will use the customizable areas of the venue to appeal to the incoming hoops crowd as well as targeting marketing strategies.

“We have a few Hall of Famers who also played basketball,” Beaudin said. “We’ll find those stories where we’re able to connect the dots. We’ll customize some of our temporary exhibits to cater to the teams.”

READ MORE: Nashville’s Left Field Restaurant Aims to Draw Fans Year-Round

An event like March Madness presents a trickier marketing challenge than, say, a Super Bowl. Without knowing which teams will be participating until the week before, long-lead advertising isn’t an option. In that case, the digital arm, including everything from targeted social media campaigns to geo-sensed suggestions in apps like Google Maps becomes key.

Beaudin says the Hall will also do social outreach to specific fanbases and work with the city’s visitors’ bureau to ensure the Hall appears on event-related information and pops on organic and paid search.

“As the list of potential teams for the Final Four narrows, we’ll start our marketing plan and we’ll do a lot of social and a lot of paid search once we specifically know who’s coming because we can get very targeted with that and reach those specific fan bases,” Beaudin said.

And as much as these crowd-drawing events help boost the Hall’s visibility among nearby visitors, Beaudin says solidifying themselves as a standalone destination and consistent venue for standalone events is a focal point for long term success. The Hall has started to make headway there as the annual host of SEC media days and ESPN’s College Football Awards show.

“Our goal is to not only capitalize on the fact that Atlanta is so good at bringing in these events but to continue to be a part of bringing them in and be part of why marquee events are coming here,” Beaudin said.

The approach seems to be working, too.

“The thing I’ve heard over and over again about the move is the accessibility now being in Atlanta. It’s just so much more accessible as a destination and as a venue and a partner for events [that] are had here that weren’t in the old location [in South Bend, Indiana],” Danny Wuerffel, who was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2013 after leaving Florida for the NFL following the 1996 season with a national title and a Heisman Trophy, said.

“It’s this unique space and experience that’s centered on football but really is available to everyone. The diversity of different functions they can and have hosted is really valuable.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jun 15, 2025; Seattle, Washington, USA; Botafogo owner John Textor inside the stadium before the match during a group stage match of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at Lumen Field.](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26465842_168416386_lowres-scaled.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)