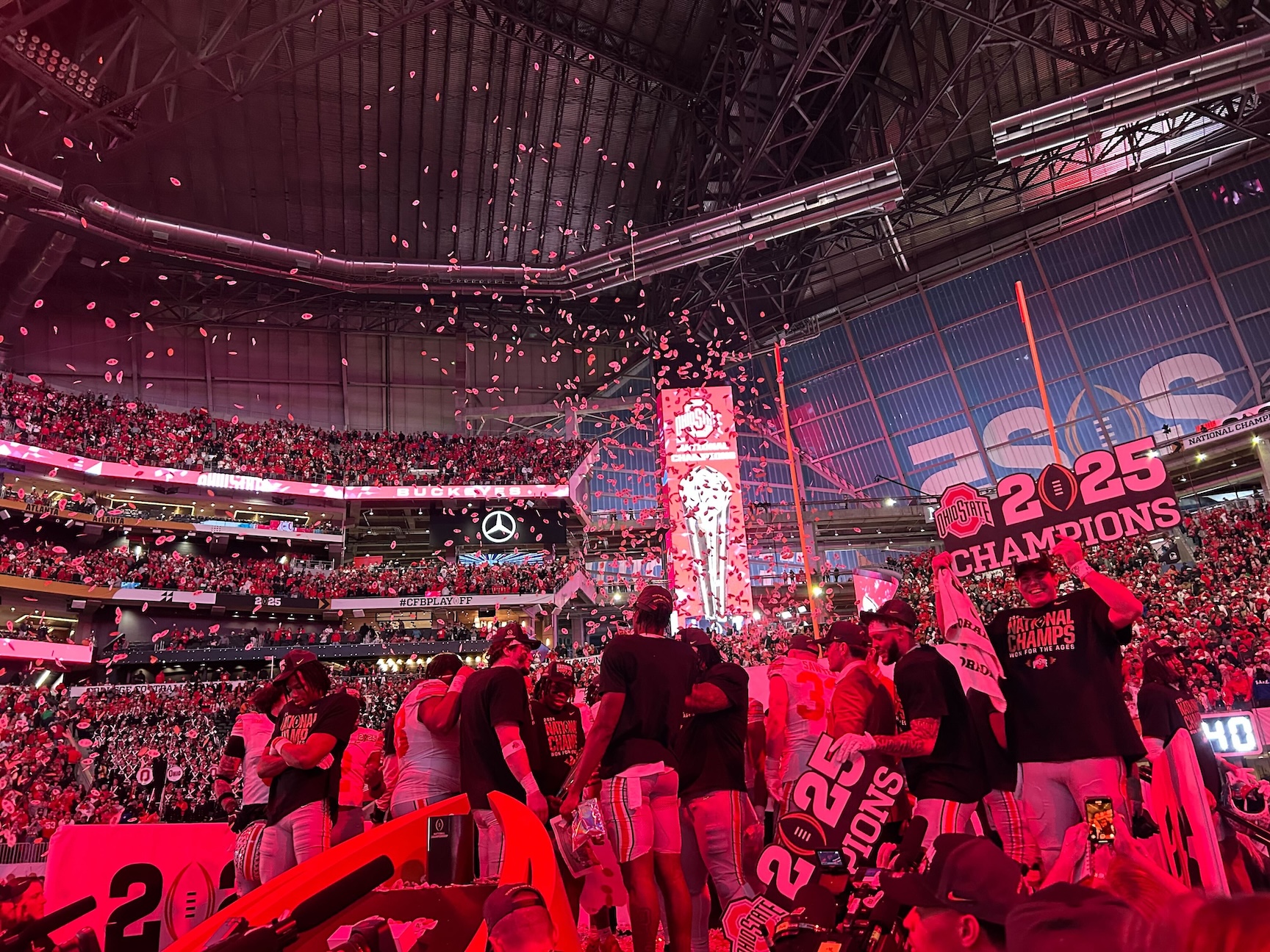

ATLANTA — The first-ever 12-team College Football Playoff culminated Monday night with an Ohio State national championship at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta. CFP executive director Rich Clark was all smiles on the field after the game, wading through fans, media, players, and red-and-white confetti. He told Front Office Sports that his first year on the job was “just amazing.”

For all the picture-perfect success of the CFP, the sport itself is facing an identity crisis. College football has never looked or operated more like a pro league, and the multimillion-dollar CFP has grown into an even bigger corporate behemoth than before. And yet, the players who generate those billions are still considered amateurs by the NCAA and its administrators.

The CFP doesn’t control player classification, but it has certainly benefited from not having to share its earnings with athletes. The entity is a for-profit LLC, unlike the schools and conferences it features, and the NCAA, which runs every other championship. It has enjoyed a multimillion-dollar deal with ESPN, lucrative corporate partnerships and surrounding events, a contract to incorporate the century-old New Year’s Six bowls into its structure, and a rotating schedule of national championships in NFL stadiums.

The 12-team media contract with ESPN, which officially begins in 2026, totals a whopping $7.8 billion over six years. In combination with corporate sponsors, like Allstate, Capital One, and AT&T, the Playoff will earn enough to distribute $116 million per year in prize money to teams alone, not including six-figure payouts for each Playoff-eligible team through the Academic Performance Rating.

For a brief moment in December, the expanded CFP felt like a quintessential college event. Four teams hosted first-round campus games—events marked by the pageantry and tradition that makes the sport unique, from fans braving the cold in the shadow of Notre Dame’s “Touchdown Jesus” mural to Texas’s longhorn mascot Bevo trotting into Texas Memorial Stadium.

But after the first round, the event swelled into a corporate giant. The quarterfinals and semifinals were played at neutral-site bowl games to satisfy lucrative CFP and conference contracts with the New Year’s Six.

The championship, which is always played in an NFL stadium, was the culmination of a weekend of festivities that in some ways rivals—or has become larger than—the men’s Final Four: a convention center-sized fan-fest, a weekend of media obligations for players and coaches, and an innumerable number of industry meetings and events. The get-in ticket price was $2,000 a seat, and some of the biggest packages included exclusive parties featuring ESPN personalities (and their dogs) and tailgates run by corporate hospitality program RevelXP.

Now, it resembles the NFL, running for an entire month rather than just two weeks.

The increased number of games, of course, feeds the television revenue, more than doubles the opportunity for corporate sponsor activations, and gives players more opportunities to participate. But it increases the chances of injury, which is why the NFL had to collectively bargain with its players for a longer season. Both Notre Dame coach Marcus Freeman and Ohio State coach Ryan Day told reporters this weekend that they shifted their overall season preparation and practice strategies to ensure they had the attrition to make it through 16 weeks of football.

Players have made multiple attempts to form a formal, legal union over the past 10 years. But despite recent failures, they still seem to have an appetite to organize.

The athletes have made strides in earning rights since the arrival of the NIL (name, image, and likeness) era, and could earn even more if revenue-sharing is approved for next season. (Ohio State is estimated to have paid its football players $20 million, with part of that funding coming from fan events like the one held by Ohio State’s NIL collective, THE Foundation, in Atlanta this weekend.)

But the players seem to know there’s more to go around. And that doesn’t just mean money—it means health benefits, worker protections, and the ability to maintain their freedom to transfer. Above all, though, they seem to want a bigger voice than their “amateurism” status allows them.

Just a few miles away from the CFP festivities Saturday, college football players from power conference teams across the country gathered to explore creating a union.

“Athletes have been treated like employees for a long time, as far as their time commitments, where they’re supposed to be, all those things,” Jim Cavale, cofounder of Athletes.org, the group that hosted the event, said Saturday. “It’s just, now, we have the finances being brought into it.”

But until they get some sort of formal organizing power, the players won’t have a say in what the future of college football looks like. College football looks, feels, and earns money like a pro league. Will its power brokers ever concede to calling itself one?

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)