The enduring power of a Super Bowl commercial can make or break careers on Madison Avenue.

Some of the best: Apple and ad agency TBWA/Chiat/Day will celebrate the 40th anniversary of the most famous Super Bowl TV commercial of all time: “1984.”

Anheuser-Busch, which has aired at least one ad every year since 1975, debuted its famed Budweiser Clydesdales concept in 1986. The series has grown into one of the most recognizable ad campaigns on U.S. television.

And Volkswagen charmed audiences with its 2011 commercial, “The Force,” showing a tiny Darth Vader using the Force on his Dad’s Passat sedan. (Tim Ellis, the VW client behind the classic spot, now serves as chief marketing officer for the NFL).

But for every landmark, there’s a Super Bowl spot that exploded like a stink bomb.

Among the worst? Try Larry David pushing cryptocurrency FTX. Or Nationwide Insurance’s notorious “Dead Kid” commercial. And don’t forget Just for Feet, which may take the prize for most offensive Super Bowl spot of all time.

Because Super Bowl ads are the most expensive spots on the market — those that consistently reach the most viewers — a failure can cause anything from a PR disaster or a lawsuit to going out of business altogether.

“It’s like Open Mic Night. Everybody wants to get up and wow the crowd. But you better wow the crowd. Or you’ll get the hook,” Ernest Lupinacci, an award-winning brand consultant and creative director, told Front Office Sports. “You’re either going to bring down the house. Or get booed off the stage.”

A $7 Million Crapshoot

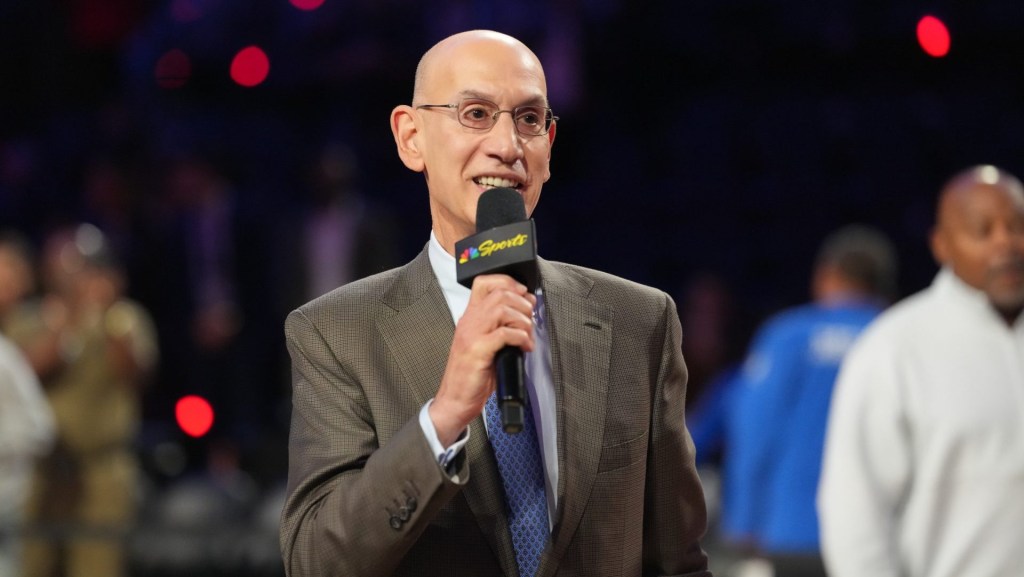

Super Bowl in-game ad spots first cracked the $1 million mark in 1995. This year, brand marketers will pay a record $7 million for in-game spots during Fox Sports’ telecast of Super Bowl 57 on Feb. 12.

That’s just for airtime. It doesn’t count the millions in production costs or the big-money fees paid to top directors.

But it’s often worth rolling the dice on the High Holy Day of Advertising.

The Super Bowl annually generates the biggest TV audience of the year. NBC’s coverage of last year’s Super Bowl 56 between the Los Angeles Rams and Cincinnati Bengals reached a total audience of 208 million, according to the league — roughly two-thirds of the U.S. population.

Besides the game’s enormous reach, it’s the one day of the year where advertisers are guaranteed consumers will watch their commercials. Many casual fans watch more for the funny, celebrity-filled spots than the football.

But buyers beware. On Super Bowl Sunday, everybody’s a critic, said Lupinacci. Part of the day’s fun is debating what ads are good and which ones aren’t, at parties or on social media.

Marketers eager for Super Bowl glory might not realize the risk/reward gamble, warned Lupinacci. Those who take the plunge are effectively volunteering to have their ads judged by the American public — and armchair critics can be merciless.

Here are three examples of big-time flops on Madison Avenue’s biggest stage. Sometimes the best Super Bowl spots are the ones you never air.

The Failure of FTX

Not every failed Super Bowl commercial flops immediately.

Some may seem innocuous or even clever when they first air — but they age poorly, becoming the punchline of a joke for a brand now in the dumps.

Take the FTX 2022 commercial — now not only an emblem of its demise, but the subject of multiple lawsuits.

The full ad stars Larry David, seen in multiple scenes voicing his (typical) skepticism over the utility of “inventions” like the fork, the lightbulb, and even the wheel. The final shot features an actor presenting David with FTX. “Eh, I don’t think so,” David responds. “And I’m never wrong about this stuff.”

Viewers are urged not to “be like Larry” and “miss out on the next big thing.”

But as it turns out, David was right. The ad now looks like an ironic prophecy for a failed enterprise.

After being valued at a $23 billion and inking multiple sports-related partnerships in January 2022, FTX declared bankruptcy — and founder Sam Bankman-Fried was arrested on fraud charges.

Clearly, FTX spent money it didn’t have on the commercial — $6.5 million on securing the ad spot alone, not including the cost of production.

The commercial’s retrospective stupidity and price tag are the least of the beleaguered company’s worries, however.

In November, a disgruntled customer filed a lawsuit against multiple celebrities including David for promoting the failed enterprise. The same firm behind that lawsuit filed another federal civil complaint in December on behalf of another FTX customer, with many of the same allegations and a long list of defendants.

Days after the second lawsuit, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission filed a civil complaint in federal court against the company for misusing certain funds for marketing expenses, including the commercial.

Litigation is ongoing in all three cases.

Not The Dead Kid, Please

The Super Bowl is one of the biggest party days of the year. Fans gather to laugh with friends and families. That’s why getting super-serious (or worse) in Super Bowl commercials can backfire. Just ask Nationwide.

The insurance giant was trying to focus attention on the tragedy of childhood deaths from preventable household accidents. Enter: a 45-second commercial in 2015 showing an adorable young boy relating all the things he would never experience — because he was dead.

In the spot, viewers saw images of the tot riding his tricycle, getting kissed by a little girl on the school bus, and sailing with his loyal Labrador Retriever.

“I’ll never learn to ride a bike. Or get cooties. I’ll never learn to fly. Or travel the world with my best friend. And I won’t ever get married,” the boy laments. “I couldn’t grow up. Because I died from an accident.”

Cue a maudlin, piano version of the familiar Nationwide theme and the mournful narrator: “At Nationwide, we believe in protecting what matters most: your kids.”

The bleak spot was morbidly effective, but also a downer. Many viewers called it creepy and depressing. Others needed a stiff drink.

Film-maker Judd Apatow joked about the tone-deaf spot, tweeting: “Exciting game but that damn Nationwide commercial haunts my dreams and my waking life.”

Comedian Jerry Seinfeld also weighed in: “Upset about Nationwide and their dead kid.”

Nationwide issued a backpedaling statement reading: “The sole purpose of this message was to start a conversation, not sell insurance.”

Mission accomplished.

Shoes with a Side of Racism

In 1999, there was one ad so bad that the brand sued the ad agency.

The Super Bowl XXXIII ad featured a barefoot Kenyan runner moving across an African landscape as two white men in a Hummer tracked him down, a depiction AdAge described as something akin to “some sort of colonialist fever dream.”

The runner was drugged and awoke with new white running shoes, which he protested by screaming “Noooooo!” The Just For Feet tagline followed.

Dueling lawsuits came within weeks.

Saatchi & Saatchi sued Just For Feet in federal court seeking $3.2 million in damages — the amount the shoe retailer with about 140 locations at the time failed to pay for the ad about a month after the Super Bowl. Days later, Just For Feet sued Saatchi & Saatchi and Fox, which broadcast Super Bowl XXXIII.

“As a direct consequence of Saatchi’s appallingly unacceptable and shockingly unprofessional performance, Just For Feet’s favorable reputation has come under attack, its business has suffered, and it has been subjected to the entirely unfounded and unintended public perception that it is a racist or racially insensitive company,” Just For Feet wrote in its lawsuit.

Saatchi & Saatchi and Just For Feet settled. The lawsuits were voluntarily dismissed.

“We were frankly kind of horrified. But Saatchi & Saatchi assured us this was the best thing they had ever done,” Just for Feet CEO Harold Ruttenberg told Salon.

Just for Feet’s issues were broader than the awful ad. It filed for bankruptcy protection in late 1999.

But wait, there’s more.

Accounting fraud was uncovered that led three former execs to plead guilty to overstating Just for Feet’s earnings by $8 million, a scheme The Wall Street Journal reported ran from 1996-98. In 2007, five outside directors on the defunct company’s board agreed to a $41.5 million settlement.

High Stakes

Ultimately, marketers have to remember they’re playing a high-stakes game within the game.

Most consumers forget the average Super Bowl commercials, according to Lupinacci, a former Nike copywriter who recently co-produced the Paramount+ mini-series, “The Offer.”

They only remember the best — and the worst, Lupinacci warns.

“If you bet the farm on a Super Bowl commercial, and you lose the farm, you can easily be out of business.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)