The football teams taking the field this fall are the most expensive since the NIL (name, image, and likeness) era began in 2021.

Last year, Ohio State won the College Football Playoff national championship with a roster rumored to be worth about $20 million—among the highest-paid in the country, alongside Texas and Oregon.

But this year, $20 million may not be enough to field a title contender.

Teams needed about $15 million to stay competitive in the power conferences last year; but this year, they’ll need $25 million, Rob Sine, CEO and cofounder of NIL collective operator Blueprint Sports, tells Front Office Sports. Quarterback numbers had doubled, he added.

The Buckeyes, who will kick off their season on Saturday in Columbus, reportedly paid $35 million for their team this year. Their opponents—the No. 1 Texas Longhorns—cost between $35 and $40 million, according to one report (though Steve Sarkisian later denied it).

The reason: The House v. NCAA settlement, which was approved in June and allowed a combination of millions in revenue-sharing dollars and a flood of “front-loaded” outside NIL collective deals that created staggering price tags this offseason. And the inflated rosters may not go down anytime soon.

“It was like the coaches won the lottery,” Sine says, “and didn’t know how much they won yet.”

The terms of the House settlement were first revealed in 2024. In the first year of the revenue-sharing era, each Division I school would offer up to $20.5 million across all sports in its athletic department. Power conference schools were required to participate in some fashion; non-power-conference schools could opt in if they so chose (and the vast majority of them did).

The settlement also placed new restrictions on outside NIL deals, which would not be counted toward the revenue-sharing cap. All deals over $600 would have to be submitted to a clearinghouse—software created by Deloitte called NIL Go—to determine whether the deal was considered a fair-market-value true NIL opportunity, or whether it was pay-for-play in disguise. The power conferences created a new enforcement entity called the College Sports Commission to run NIL Go and oversee enforcement.

Players wouldn’t have to report any deals that were signed before June 11 (when NIL Go opened) and that were paid in full before July 1. That created a loophole: Schools could continue offering de facto pay-for-play NIL deals as long as they were completed before the aforementioned deadlines.

Players not only knew about this phenomenon, but their agents also used it as a negotiating tactic.

“When athletes came forward for this year’s [negotiations] … it was not the same valuation as last year’s class,” one power conference collective operator tells FOS. “They viewed themselves [as worth] significantly higher because they viewed rev-share as a new pool of money to be allocated.” In other words, players saw the rev-share dollars as additional compensation above and beyond NIL collective deals they’d received over the past few years.

To prepare, schools hired general managers for teams or athletic departments for revenue-sharing “salary-cap management”; some began executing rev-share contracts (with clauses that they were valid only if the settlement was approved). Many collectives “front-loaded” their NIL collective deals so they wouldn’t be scrutinized by NIL Go.

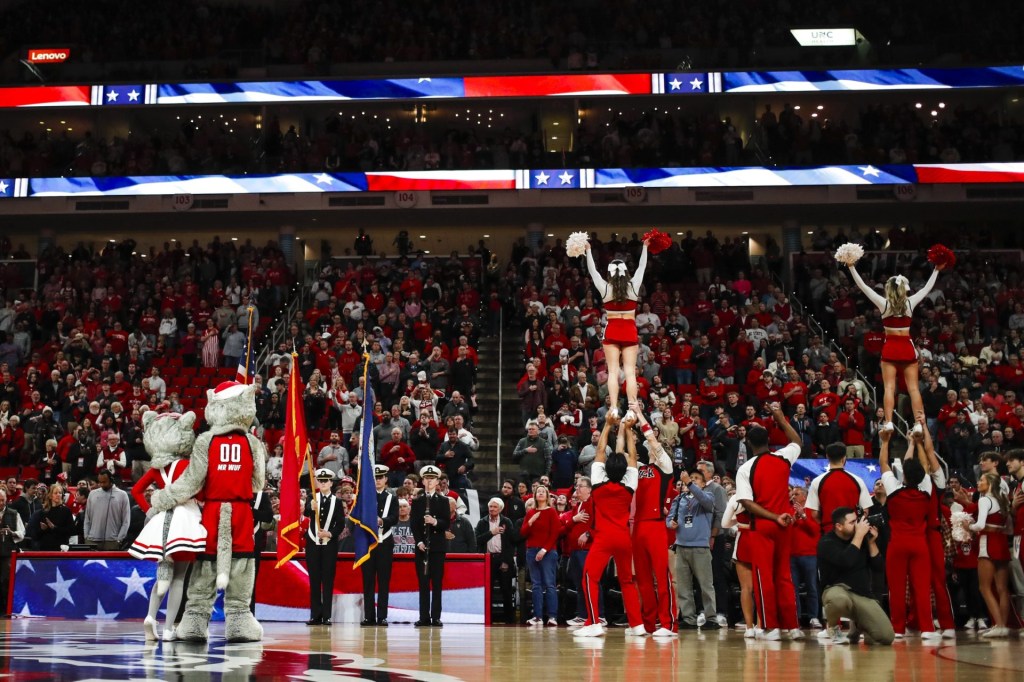

For example, days before the settlement was approved, Texas Tech athletic director Kirby Hocutt told FOS that his collective, The Matador Club, was operating business as usual. “The longer that this House settlement takes, you just extend an active transfer-portal environment where collectives can be active and engaged,” Hocutt said.

Matador Club cofounder and Texas oil billionaire Cody Campbell told FOS: “It was definitely expensive.” But the Red Raiders had the money: Campbell also said they raised $63.3 million from thousands of donors over the lifetime of their existence.

Judge Claudia Wilken issued an approval of the House settlement on the evening of June 6—in the middle of the Women’s College World Series.

The prevailing feeling across the industry was one of relief. After all, schools had known the terms for months. Athletic departments had already prepped; contracts had already been signed. All that was left to do was make sure players cashed their checks.

On June 11, the College Sports Commission (CSC) officially launched the NIL Go service. That’s when any new NIL deals needed to be reported to the clearinghouse.

But schools still had until July 1 to finish paying players existing deals that were signed before the settlement was approved. On June 30, the day before the House settlement terms would technically be implemented, more than $20 million of NIL collective dollars passed through Opendorse’s system, the NIL company said.

As for whether the CSC will try to retroactively punish schools for front-loading, the answer is no. The CSC doesn’t have jurisdiction over any deals executed before the NIL Go reporting deadlines.

It’s unclear whether the “NIL bubble” will pop in future years. That was supposed to be the point of NIL Go, at least. But the CSC had to backtrack after issuing guidance that would have generally barred NIL collectives from participating in the landscape. Going forward, collectives and boosters can still operate and pay players—they just have to be more creative.

Contracts are “definitely inflated compared to what they were last year—by a long shot,” the collective operator said. “I would argue that’s not going to go down.”