In 2025, prediction markets experienced their Big Bang: an explosive expansion that was fast, chaotic, and impossible to contain. Experts say 2026 will likely bring consolidation, as well as some clarity on legality and regulation.

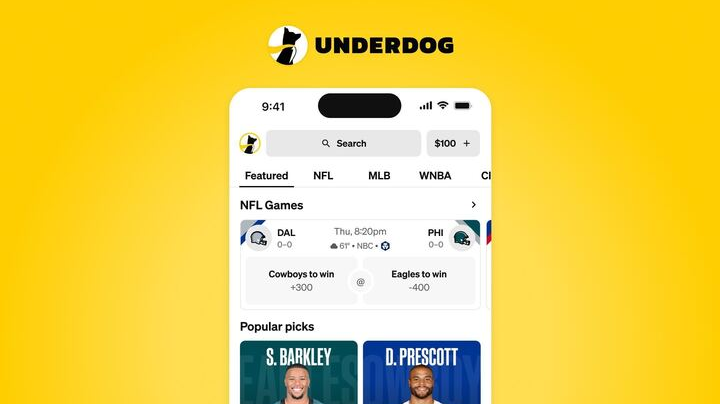

This year, billions of dollars poured into platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket, and sports event contracts surged to become the center of their business. Although some regulators reacted, most watched from the sidelines. Meanwhile, the number of players in the industry increased with each passing month: From Robinhood, PrizePicks, and Underdog to FanDuel, DraftKings, and Fanatics, everyone wants a piece of the prediction-markets pie. President Trump is even launching his own. (Donald Trump Jr., meanwhile, is an official adviser to both Polymarket and Kalshi.)

Although prediction markets offer more than sports—users can put money on everything from whether it will rain in New York City today to what words President Trump will say in a speech—the allure for sports event contracts is simple: It’s a way for companies to offer what is essentially identical to sports betting in all 50 states, even those where the practice is still prohibited.

The underpinning claim, which is being argued in multiple legal fights, is that there’s a technical difference between betting and trading. When you place a bet on a prediction-markets site, the companies say, you’re actually investing in a futures contract.

‘Pouring Gasoline on a Fire’

Stephen Piepgrass, a partner at law firm Troutman Pepper Locke, whose practice includes counseling clients in the gaming industry, says the rapid growth of prediction markets can be likened to what happened when alcohol delivery became widely available during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Suddenly, you could get alcohol delivered to your home, and boom—brand-new market,” he tells Front Office Sports. “You merge the technology we have with the elimination of the stigma on prediction markets, and it’s like pouring gasoline on a fire.”

The explosion has brought intense legal scrutiny. Kalshi, for example, was hit with cease-and-desist orders from 10 state regulators, most recently in Connecticut (Robinhood and Crypto.com have also been named in a number of the cease-and-desists). In turn, Kalshi has sued regulators in multiple states, including Nevada and New Jersey.

Kalshi was separately hit with a proposed class action filed in New York in November that claims thousands of users were deceived into losing money. Platforms including Kalshi and Robinhood have argued in court that their event contracts fall under federal oversight by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), preempting state gambling laws. In total, there are more than a dozen lawsuits winding through the system, both in state and federal court. There have been some early decisions—like the judge in Nevada ruling the state’s gambling regulator can seek to stop Kalshi from offering sports event contracts in the state—although none of the cases are close to concluding.

Despite unanswered questions about the legality of prediction markets—especially in states like California, Texas, and Georgia, which don’t allow any form of sports betting—some major agreements between platforms and leagues and news organizations have helped bolster the industry’s legitimacy. Kalshi and Polymarket are both official partners of the NHL, and Polymarket has a deal with UFC. Kalshi has deals with CNN and CNBC, and Google intends to integrate data from both Kalshi and Polymarket.

Pushback From Leagues

But the platforms still have work to do. Many other marquee players—including the NFL, NCAA, NBA, and MLB—have yet to come on board. NCAA president Charlie Baker recently said the current state of prediction markets is not only not sustainable, but potentially “catastrophic.” The NFL and NBA have each expressed concerns about the lack of regulation and potential harm to integrity of games, and MLB over the summer sent a memo to players directly prohibiting them from engaging with baseball event contracts.

As leagues continue to grapple with the rise of prediction markets, state attorneys general are weighing whether victories against one platform might set precedents for others. The platforms themselves continue to expand aggressively, betting on inevitability—the operator of the New York Stock Exchange agreed in October to pour up to $2 billion into Polymarket, while Kalshi in early December announced $1 billion in new funding. Although Polymarket and Kalshi each insist they aren’t running gambling platforms—but are instead building something bigger with society-altering implications—sports are a primary driver of business for both. Polymarket’s U.S. relaunch started with just sports event contracts, and sports accounts for an overwhelming percentage of Kalshi’s volume (it hit $331 million in trading volume in December, a new record).

Melinda Roth, a professor at Washington and Lee University School of Law, says she’s “old enough to remember when trading cost money.” She points to a time before app-based trading existed, when personal investing was primarily done on platforms like Schwab, Fidelity, and Merrill Lynch.

“Robinhood came along and totally disrupted all that,” she tells FOS. “Now, we trade 24/7 and we don’t think anything of it.”

“The train has left the station,” she says. “Prediction markets are going to exist.”

Who’s Left Standing?

Experts say consolidation is all but guaranteed; there’s simply not enough room in the market for so many different platforms. Jay Ritter, a finance professor at the University of Florida, tells FOS that while both Kalshi and Polymarket are candidates for initial public offerings in the long term, for now they appear to be focused on growth.

“Each company wants to aggressively gain market share,” Ritter says. “There may be room for a few survivors, but any platform with small market share is likely to see its share go to zero rather than be profitable. It’s a winner-takes-most game.”

“If one of them falls too far behind the competition, it will fail,” Ritter adds. “Think of MySpace versus Facebook 15 years ago.”

As the industry continues to expand and courts wrestle with its legal status, the ultimate resolution may lie at the very top of the judicial system. “At the end of the day, whether it’s in 2026 or 2027,” Piepgrass tells FOS, “this may very well end up at the Supreme Court.”