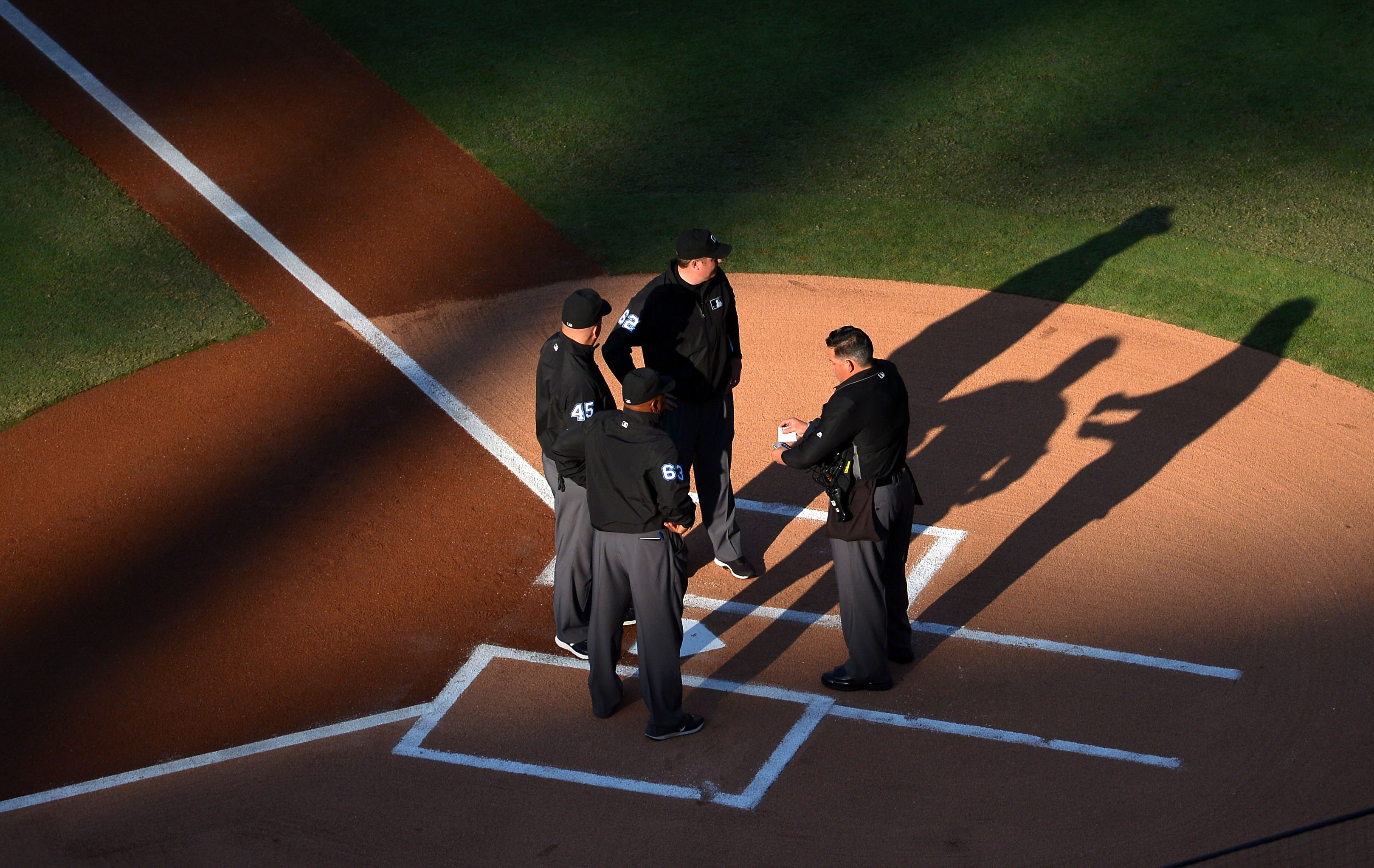

There’s nothing more frustrating for baseball fans and players alike than seeing a pitch that they think was called incorrectly by an umpire.

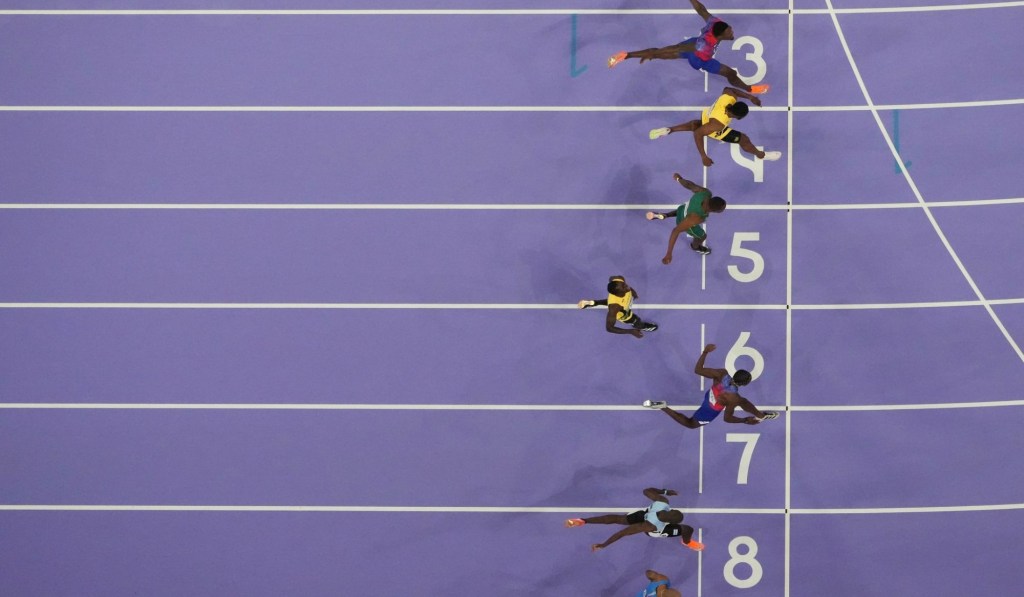

Enter TrackMan, the company being tabbed by MLB and the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball to test a radar-tracking system that will assist home plate umpires in calling balls and strikes. The technology goes league wide in the eight-team ALPB starting on July 25.

In recent years, MLB has been diving deeper into the tech boom leagues like the NBA and NFL have experienced. Looking for baseball affiliates willing to test new experimental equipment and rule changes, MLB reached out to Rick White, president of the ALPB.

After White’s ALPB agreed to serve as MLB’s guinea pig, it began working with the Copenhagen-based TrackMan last December. TrackMan’s automated ball-strike system, or ABS, debuted on July 10; a season that will be analyzed by MLB before deciding if it could also implement the technology in future seasons.

While it was founded in 2003 as a golf startup, TrackMan has found a strong niche in baseball as well since it started its own division for the sport in 2008. Currently, TrackMan is used by all 30 MLB teams and is featured globally in countries like Japan, South Korea, and Latin America.

“The [baseball] teams we were working with really pushed us into the game environment because they didn’t want practice information,” said Cullen McGowan, TrackMan’s manager of baseball operations. “They needed game information – so we always thought we were going to come into baseball through the player development or the coaching route because that’s what we did in golf and that’s really who we are as a company.”

According to McGowan, baseball began taking notice of TrackMan after seeing its technology advance the slow-to-react golf industry. Emphasizing precision and reliability, it could monitor the full trajectory of any golf shot. From green-side pitches to drives off the tee, TrackMan could also calculate a shot’s 3D trajectory and landing position with an accuracy of less than one foot at 100 yards – all in one second.

In its mission to help athletes improve through technology, TrackMan boasts a decorated cast of supporters. They include 350 PGA Tour players – from Dustin Johnson to Rory McIlory – famed golf coaches Sean Foley and Jim McLean, the U.S. Ryder Cup team and over 100 U.S. universities.

“At the core of TrackMan DNA’s is a one-on-one interaction with the player and a coach,” said McGowan. “In golf, that’s pretty apparent with the immediate feedback at a driving range and just how that sport works with the instruction and the amount of feedback that those athletes are used to.”

When TrackMan officially opened its baseball division in 2008, MLB teams were stunned at the data they were being provided. From spin rates to fastball movement to pitch trajectories, it was a testament to the analytical mentality infiltrating baseball operations.

Fast forward to 2019, and TrackMan has made an effort to expand its baseball portfolio beyond MLB. As of March 2019, the system has been installed at 54 Division I schools and collegiate summer leagues such as the West Coast League and Coastal Plains League. It has even inspired digital apps like Pitchgrader, which takes data from TrackMan and other competitors and condenses it into reports and visualizations understandable to its users.

READ MORE: Baseball Teams Aim To Bring Fans In, While Keeping Phones Out

Years later, the beginning of an ALPB-TrackMan partnership began to percolate. According to Rick White, president of the ALPB, MLB met with him in December 2018 to discuss the possibility of a collaborative relationship.

According to White, MLB made an offer the ALPB had long been awaiting. If the league agreed to employ MLB’s equipment and rules changes during the 2019 season, MLB would then install advanced analytical equipment into its eight teams’ ballparks. After years of waiting, White finally got his wish and, come February, united with MLB for this unprecedented opportunity.

“We want to give our players every opportunity to be seen every night by 30 [MLB clubs], in addition to the numerous scouts who come to our games to see them in person,” said White. “So that was the genesis of the relationship that we consummated here in February [with MLB].”

TrackMan’s work was put to the test on July 10 at the ALPB’s 2019 All-Star Game in York, Pa., which incorporated ABS. Initially, White did acknowledge that he did receive plenty of skepticism from Atlantic League players, umpires, and coaches.

According to White, there was much confusion surrounding the ABS. What is expected of umpires? Should there be worry that this is the first step in baseball replacing umpires with automation? With coaches and players, White was told that they weren’t confident with ABS’s accuracy. Would it really prove to eliminate the human error often associated with umpiring?

And last, but perhaps most importantly, how does ABS work?

According to White, answering this question took months of preparation and trial-and-error. In the early stages, the ALPB and TrackMan experimented with radio-signal technology to relay the pitch-call to the umpire. Both realized very quickly that a much stronger source was needed to reach PeoplesBank Park, which seats 5,200 people and is 1,031-feet wide.

To accommodate the ballpark’s size, they then switched over to WIFI technology and added a transmitter as well. From there, the pair began testing umpire equipment, and decided on using an earbud and headphones attached to a cell-phone acting as both a transmitter and receiver.

Attached to all of this equipment is what White calls a “depressed box communicator” that resembles a lavalier. This lavalier-like mechanism is what umpires use to communicate to an operator in the press box. According to him, as the ball crosses the plate, the umpire should instantly hear only one of two words: “ball” or “strike.”

For fans not looking for how ABS was being implemented, they might have missed it. Home plate umpire Brian deBrauwere wore an Apple Airpod in his right ear, which was linked to an iPhone in his pocket. That phone relayed the call from the TrackMan communicator. With this integration, umpires are given the ability to override the computer’s decision, which considers a pitch a strike when the ball bounces and then crosses the zone. TrackMan also does not evaluate check swings.

Despite some minor difficulties in the All-Star Game, both McGowan and White have dubbed the night a success. Numerous media outlets nationwide flocked to PeoplesBank Park to witness the future of baseball. To them, attention is being brought not only to baseball’s open-mindedness, but a world in which umpires and robots can co-exist.

“It’s hard for me to fathom that at some point in time an automated system can cover [every baseball game],” said White. “We want the umpires to be in charge. We like the umpires being there. We’re not trying to replace umpires, we’re trying to augment what they do with a reliable ball-strike system.”

“Whether it’s [because] technology is driving it, I think that technology is really bringing the various groups of players, coaches and front office more together,” said McGowan. “It’s certainly changing the type of people in the organization. I think this is just natural and the technology is more [about] bringing in groups together rather than pushing them apart.”

For McGowan and TrackMan, their expansion extends beyond the ALPB. It has also been working with East Coast Pro Showcase, a not-for-profit event run by MLB scouts that provides a platform for amateurs aspiring to become professional baseball players.

According to McGowan, East Coast Pro Showcase was once the prototypical “old-head” baseball organization that stuck to tradition and resisted technology. Now that it’s working with TrackMan, McGowan views this as a chance for the pair to learn from each other.

READ MORE: How do Adam Silver and Roger Goodell view influence of tech?

From TrackMan’s perspective, it can educate scouts on more advanced metrics to assess player talent. With East Coast Pro Showcase, it is helping TrackMan establish a rapport with scouts who are critical of its effectiveness.

Even outside of baseball, McGowan noted TrackMan’s non-baseball endeavors. When NBC broadcasted a Week 8 matchup between the Saints and Vikings last season, it debuted TV’s first-ever “field goal tracer” using TrackMan technology. It calculated and displayed three types of measurements: ball speed, apex, and “good from,” which measures the maximum distance that field-goal could be converted from.

Despite its ever-growing sports presence, McGowan does point out that there are still growing pains to endure. TrackMan is still evolving and correcting its flaws, while scouts and umpires are working to understand and properly utilize its data. For McGowan, he believes if baseball figures continue to work with TrackMan, it can be great for the sport’s future.

“Baseball is changing in that everyone is very open-minded to improving their place in the game,” said McGowan. “It’s not about how you got your place in the game — whether you’re an umpire [or not], it’s about an open-mindedness to improve that.”

“We truly feel that there’s nothing more powerful in baseball than an experienced scout and a TrackMan radar. There are flaws in our technology [in] the same way a scout can’t see everything. They can see a lot, but us together are a really powerful tool,” he said.