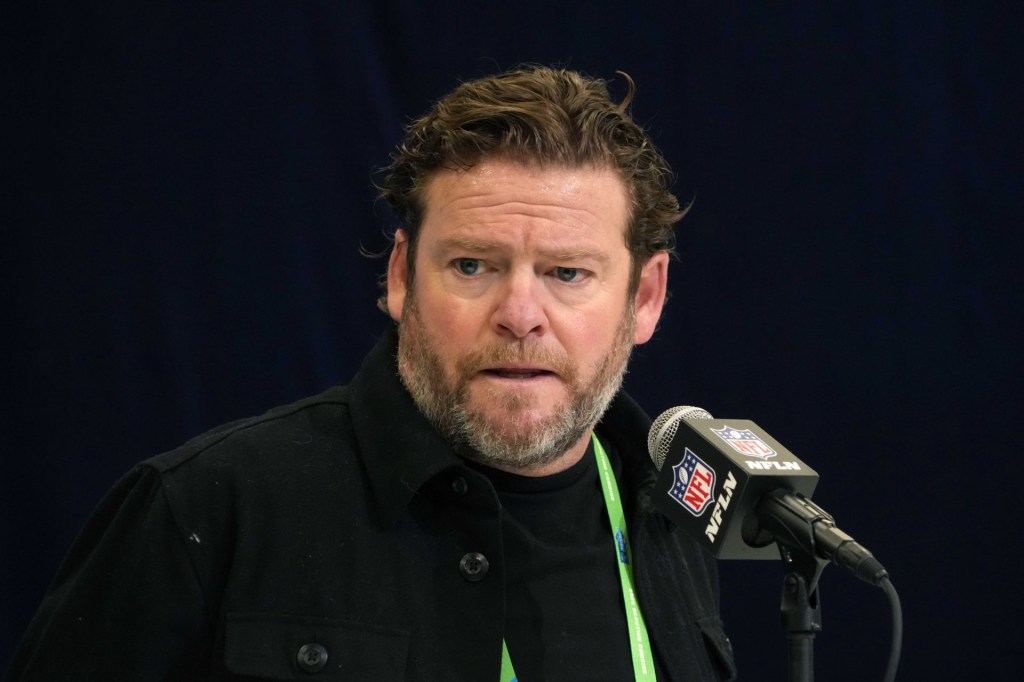

Jeff Lewis found the inspiration to launch the American Flag Football League in an unlikely place – on a field on Randall’s Island in New York City watching his son’s then-third grade flag football team.

“It put the question into my head, which is essentially: if third graders make this game so exciting, what would it look like played by the greatest athletes in the world,” said Lewis.

That came to life through the creation of the American Flag Football League, or AFFL, in May 2017. While it was launched as a safer, more accessible alternative to the National Football League, Lewis feels the league has as much in common with the NBA or MLS as it does with the NFL.

“What we see is that young sports fans love the AFFL – they love the speed and the personality and the athleticism of flag football,” Lewis said. “I think of our game as a kind of melding of the best aspects of so many sports. It’s the simplicity of soccer, the personality of the visible athletes of basketball. The wonderful strategy and urgency that really makes football is the fact that every game is really, really in doubt and matters so much.”

Lewis aimed to find out if his inclination was true through a proof-of-concept game. On June 27, 2017 at Avaya Stadium in San Jose, Calif., several former NFL stars itching for a safer playing career such as Heisman Trophy Winner Danny Wuerffel, quarterback Michael Vick, receivers Chad Ochocinco and Terrell Owens, and safeties Nick Collins and Kerry Rhodes, all lined up for a flag football game.

With almost no promotion and only streamed through YouTube and the AFFL’s website, Lewis was surprised at what the numbers showed. As of today, over 2.6 million people have viewed the game on YouTube.

That momentum carried into the AFFL’s first season, held in the summer of 2018 with a $1 million dollar prize armed with a broadcast rights deal with NFL Network.

Its second year was internally viewed as a success as well. According to Perri Gillon, the AFFL’s director of marketing, the league saw more viewers across Twitter and YouTube than in 2018, with Youtube generating an average stream of approximately 20 minutes.

In 2019, one of the semifinal games featured defending champions Fighting Cancer – who have just one former NFL player – squaring off against a Florida Fury team fielding the likes of Vick, Wuerffel, former NFL WR Jason Avant, and former NBA star and University of Washington cornerback Nate Robinson.

According to Gillon, the AFFL live stream at one point generated 15,000 people viewing the Fighting Cancer-Florida Fury encounter. This contributed to a postseason that, according to Gillon, drew in total approximately 2 million viewers and 400 million media impressions.

“One thing is we were trying to [do is] get people to get to the game,” Gillon admitted, “but as you can tell by the watch time, [Fighting Cancer vs. Florida Fury] actually kept people entertained and staying on the stream itself.”

While former NFL stalwarts like Vick and Owens have drawn fans to the league, the AFFL has also provided a platform for flag football players who have never drawn the spotlight.

Take Darrell Doucette, Fighting Cancer’s starting quarterback. Some might laugh at his football credentials – or lack thereof.

The New Orleans-based gunslinger never played college football, let alone high school. Instead, he works full-time as a baggage handler at Delta Airlines.

How can someone who works in aviation find success in professional sports? For starters, being the best in flag football.

Prior to the AFFL, Doucette was a five-time national champion in the sport, but without the spotlight. Luxurious paychecks are hard to come by in flag football, which is why the AFFL caught Doucette’s attention. With that hefty cash prize, the AFFL had the potential of making Doucette a breakout star in the sport.

“The AFFL has been able to give us regular folks a new life,” said Doucette. “As far as it being a blessing for me, myself, my team, people are learning who we are and when we go places, people know who we are.”

While the AFFL’s early streaming numbers and surplus of proven and emerging talent suggest viability, there has been reason for caution. After that highly touted $1 million payday in 2018, the 2019 season saw it dwindle to $200K – an 80% decline year-over-year.

When questioned about his league’s drastic reduction in prize money, Lewis decided not to focus on short-term thinking. According to him, the AFFL’s tenure is built for the future, even if that meant lowering the cash prize to get there.

“From day one, our goal has been to build a sustainable product that showcases the game of flag football and connects with fans,” said Lewis in an emailed statement. “Our primary focus is building long-term success – we are not in the business of making a splash for just a year or two. Because of that, we reduced the prize this season to ensure our strategy for long-term success continued to remain viable.”

Its deal with the NFL Network was not renewed either, leaving it without a linear television presence. When asked about their reasoning for departing from the AFFL partnership after one season, the NFL Network declined to comment.

Instead, the league began partnering with digital companies such as Whistle Sports, which helped facilitate its Facebook stream for the 2019 season. Another company which partnered with the AFFL was WAVE. Billing itself as the fourth-largest sports media publisher across social platforms, WAVE’s content generates upwards of 1.5 billion monthly social media views. The AFFL utilized WAVE’s vast reach on Facebook and Instagram to promote the league’s second season.

That new digital reach, plus the promotion of the streams by Vick and Robinson, led to viewers watching the league’s finale in 2019. Just under 1.6 million unique viewers tuned into the live stream that was available via AFFL social, Whistle Sports, WaveTV, and Fantom.

In April, The Association of American Football became the latest in a long-line of start-up football leagues that failed. In the build-up to year three, can the AFFL break that slate?

“If you look at any history of any professional sports league, the odds are always against you,” said Wuerffel, who joined the AFFL as an advisor in October 2018 while continuing to play in the league. “Certainly no one’s thinking [that] starting a new league [is] a shoe in.”

Wuerffel said that the league has been in contact with potential investors, some of whom were waiting to see how the second season went. That investment could potentially go towards raising the prize money back to its previous level.

READ MORE: XFL Stays the Course Amidst Spring Football Craze

“You’ve got to find [prize money] that’s significant enough to be very motivating for a lot of players to spend a lot of time and energy to prepare and get ready and then invest your own money at the same time,” he said.

Wuerffel noted the boom-or-bust reality of most start-ups. Despite the decline in prize money and change in broadcast platforms, Wuerffel, like Lewis, points to the on-field product as evidence that the AFFL can survive.

“The reason I agreed to [play flag football] is because I think it’s a fantastic game,” said Wuerffel. “I obviously love football, and this flag football format creates a ton more opportunities for a lot more people to participate than just simply tackling involved. I think there’s a huge future for flag football, so I’m happy to be apart of it.”

That future might also lie beyond the United States. Lewis boasts of the AFFL as a league of endless geographic range. With the globalization issues surrounding American football – 22 players, goal-posts, equipment, etc. – Lewis says that he’s consulted with foreign countries about expanding flag football internationally.

This fall, Lewis plans to host an AFFL international tournament fielding a U.S. national flag football team with a female squad. Then in the winter, Lewis aims to hold an event in Africa.

READ MORE: “I Thought This Was a Good Deal”: AAF Vendors Speak Out

Beyond that, he has intimated that other countries like China and India want to adopt flag football. If that holds true, Lewis’ vision extends far beyond the confines of Randall’s Island, and into a sphere which touches the globe.

“Flag football, in its kind of stripped down, natural state, really lends itself to sort of spreading around the globe,” said Lewis. “It’s a wonderful thing to think about football really as a world game. With men, women, children, everyone around the world can play this game.”