Susie Cirilli didn’t plan to center her practice on transgender athletes. But more than a decade into her legal career, the former Division I soccer player—who is also a certified WNBA and PWHL agent—is doing just that.

Cirilli is representing transgender athletes in more than half a dozen lawsuits against individual schools, the NCAA, and other governing bodies. While the Supreme Court is separately weighing state bans on transgender participation in women’s sports—cases rooted in West Virginia and Idaho that hinge on Title IX and equal protection—Cirilli’s lawsuits target a different legal theory altogether.

“The issue is discrimination,” Cirilli tells Front Office Sports. “It’s public accommodation.”

More specifically, Cirilli’s suits allege violations of state anti-discrimination laws. One claims that barring a transgender athlete from an adult amateur tennis league violated New York’s Human Rights Law, which prohibits discrimination based on gender, including “the status of being transgender.” Another alleges that preventing a runner from competing in a track race violated the New Jersey Law Against Discrimination, which forbids denying someone the ability to participate in activities because of their sex or gender identity.

Cirilli, who earned her degree from The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law, originally carved out a niche advising teams, coaches, and agents on employment and contract issues across women’s sports. A few years ago, a friend from her Philadelphia running club connected her to her first transgender athlete client, and word soon spread.

“There’s not that many people doing it,” Cirilli says. “So once I represented one of these athletes, I started getting more cases.”

As the cases piled up last year, Cirilli—a 5’3” former midfielder at the University of Vermont—decided she could use support. Since November, she’s been with Philadelphia-based law firm Spector Gadon Rosen & Vinci, where she now works alongside veteran civil rights lawyer Alan Epstein.

“Susie hasn’t done this sort of high-profile stuff before, and people are not going to necessarily agree with her,” Epstein tells FOS. “But she becomes six-feet-tall every time she talks. She has such passion and enthusiasm for what she does.”

The Cases

The work picked up during the second half of last year. In June, Cirilli filed suit in New York state court on behalf of Cammie Woodman, who claims the Tennis League Network removed her from an adult amateur women’s league after an opponent raised the fact that she is transgender.

The following month, Cirilli sued Princeton University and New Jersey track meet organizers on behalf of Sadie Schreiner, a former Division III All-American at the Rochester Institute of Technology, who says she was barred from competing as an unattached runner 15 minutes before her race was set to begin. Schreiner is also the plaintiff in other lawsuits against the NCAA, SUNY Geneseo, New York State, and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Cirilli represents long-distance runner Evie Parts, who sued Swarthmore College, members of its athletic department, and the NCAA in Pennsylvania federal court over claims her college track career was “suddenly” halted last February. That’s when the Division III school chose to adhere to a new NCAA policy that’s in line with an executive order signed by President Donald Trump aimed at restricting transgender athletes from competing in women’s sports.

In October, amateur fencer Dinah Yukich—represented by Cirilli—sued the Premier Fencing Club, USA Fencing, and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, alleging she was prohibited from competing in official events in what the complaint calls a “bigoted trans ban.”

“These are people who were already athletes, who loved to be athletes,” Epstein tells FOS. “What right do you have to stop them from doing that?”

The Backdrop

The lawsuits were all filed after Trump’s 2025 executive order, which both threatens to halt federal funding for schools that allow transgender athletes to “take over” women’s sports, and says that schools violating it could lose federal funding.

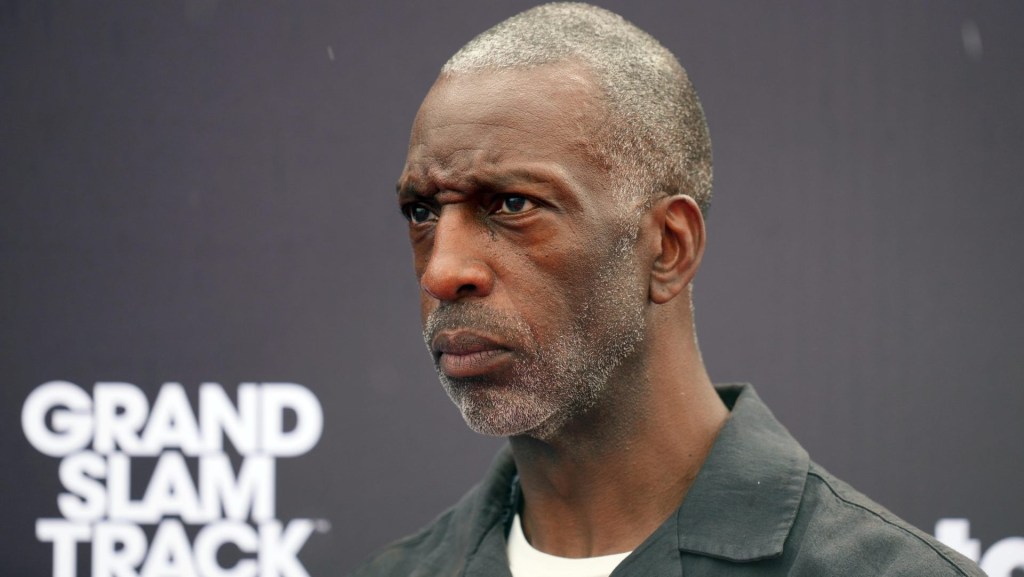

There is no official national tally of transgender athletes in U.S. college sports, but in December 2024 NCAA president Charlie Baker testified to Congress that he believed there were fewer than 10 transgender athletes among the roughly 510,000 total NCAA athletes.

A representative for the NCAA told FOS in September that while it does not comment on pending litigation, it continues to “promote Title IX, make unprecedented investments in women’s sports and ensure fair competition in all NCAA championships.”

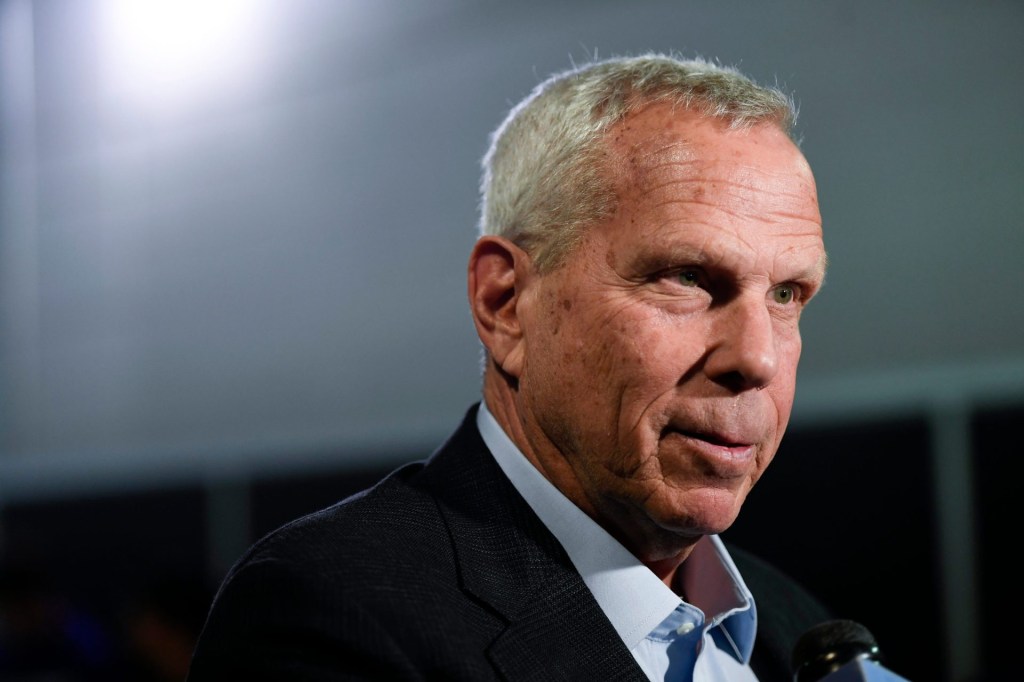

In response to the fencing lawsuit, USA Fencing CEO Phil Andrews told FOS in October that “we can’t comment on ongoing litigation,” but explained the organization updated competition-gender fields to match sex assigned at birth and contacted affected members to explain the change and offer support.

“We recognize the sensitivity of this topic and remain focused on complying with national requirements while supporting every member of our fencing community,” he said.

The Other Side

Cirilli’s stance is disputed by those who argue the issue is not inclusion, but competitive fairness. Kim Jones, cofounder of the Independent Council on Women’s Sport (ICONS), is a former All-American tennis player at Stanford University and mother of four whose children are competitive swimmers. She says she saw first-hand how competing against former University of Pennsylvania transgender swimmer Lia Thomas caused her oldest daughter distress. (Thomas was allowed to compete as a woman and won an NCAA championship in 2022.)

“Watching what sports became, through that experience for her and her peers, was the most mind-bending experience,” Jones tells FOS. “It became like I was living in the twilight zone.”

A lawsuit filed in 2024 by Riley Gaines that centered on Thomas and named the NCAA and several Georgia public universities as defendants was largely dismissed in September.

Jones rejects the idea that the debate centers on transgender inclusion rather than women’s rights, and says the issue is straightforward, even if it has become politically charged.

“The issue is not complicated,” Jones tells FOS. “Girls deserve fair access to a safe and level playing field at every age, every level. It’s actually very simple, but it’s contentious.”

Cirilli agrees the issue is simple, but feels she is on the right side of history. She likens the fight over transgender athletes to civil rights battles of the past—Kathrine Switzer becoming the first woman to run the Boston Marathon in 1967, Jackie Robinson breaking the MLB color barrier in 1947, and Renee Richards becoming the first transgender woman to play in a pro tennis tournament when she competed in the 1977 U.S. Open.

“Sports have always been a snapshot of where society is,” Cirilli tells FOS. “It’s the arena where civil rights plays out.”