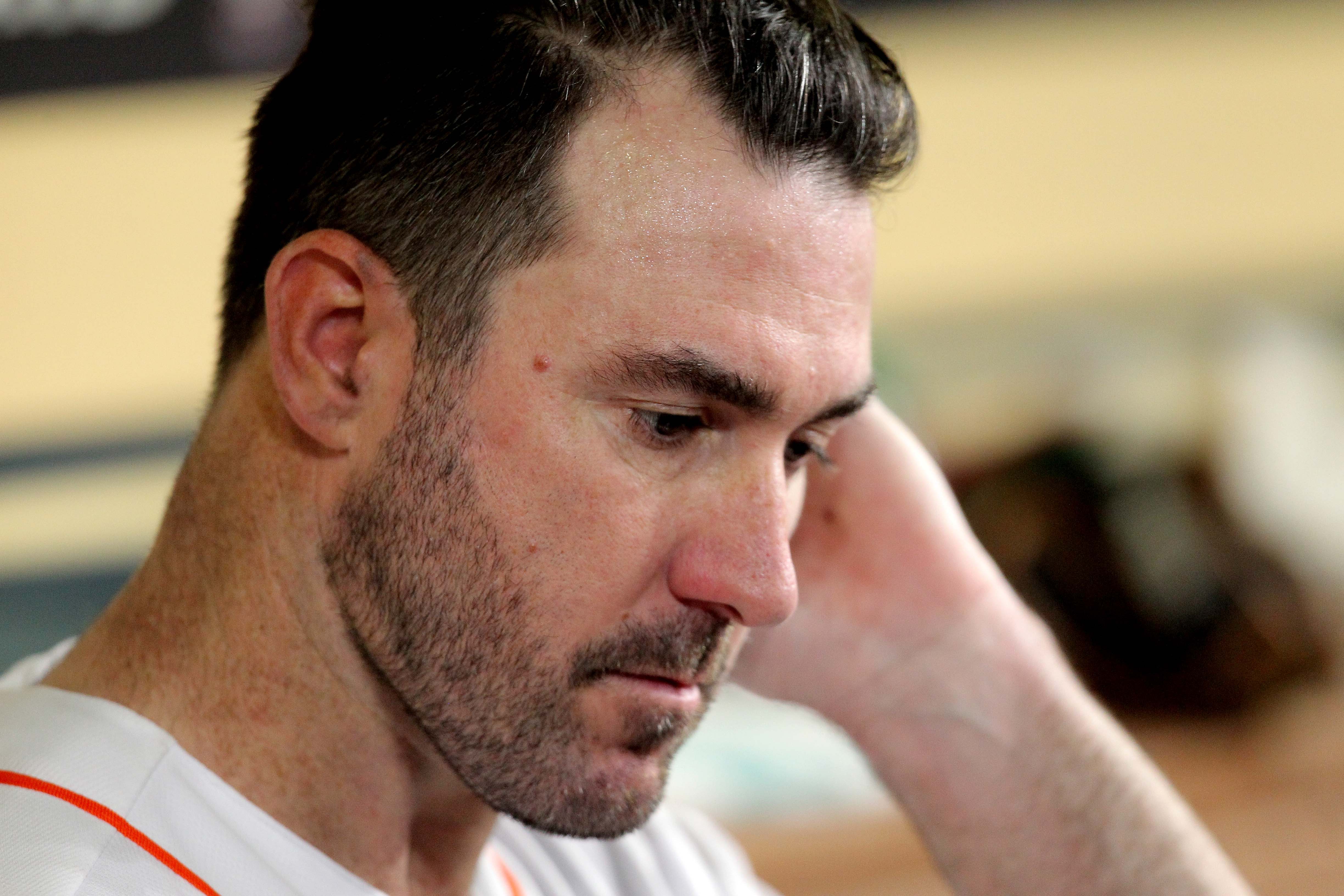

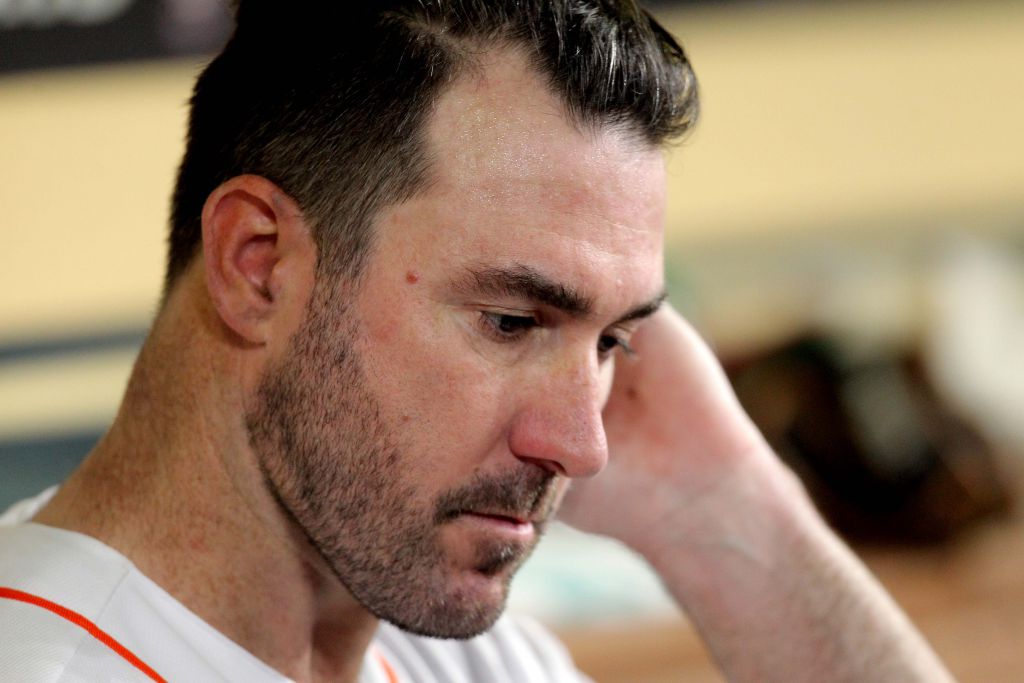

Even Major League Baseball says the Houston Astros were wrong when they denied Detroit Free Press reporter Anthony Fenech access to their clubhouse until pitcher Justin Verlander finished his postgame media session.

But last week’s Fenech vs. Verlander dust-up was just the latest example of the ongoing push-pull between beat reporters trying to do their jobs – and pro sports teams/college programs trying to protect their players and control the media narrative.

In June, New York Mets pitcher Jason Vargas and manager Mickey Callaway wanted Newsday reporter Tim Healey ejected after an ugly confrontation. A snarling Vargas reportedly told Healey he would “knock you the f— out!” The Mets later apologized to Healey, saying it “sincerely” regretted the incident.

Veteran baseball writer Jayson Stark of The Athletic said the key in these situations is two-way communications.

“I’ve never had a team official bar me from approaching a player. I’ve had players tell me they weren’t talking to me or even not acknowledge my questions or my presence. But in those situations, with very few exceptions, I’ve tried to find out from that player, either personally or through an intermediary, what the issue was,” Stark told Front Office Sports.

“Then I’ve always aspired to talk that through one-on-one if possible. That’s how almost all of these situations are always resolved, in my experience, unless it’s an extreme case.”

The situation is often relative. College football writers covering the SEC Conference, for example, probably face far more restrictions than MLB writers backed by the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA).

Still, the Astros’ treatment of Fenech crossed the line, according to MLB.

“Per our Club-Media Regulations, the reporter should have been allowed to enter the clubhouse postgame at the same time as the other members of the media,” said MLB spokesman Michael Teevan in a statement. “We have communicated this to the Astros.”

BBWAA president Rob Biertempfel expressed alarm too: “This action by the Astros violated the MLB club-media regulations, which are laid out in the Collective Bargaining Agreement, and the BBWAA expects MLB to respond accordingly and promptly.”

The incident also raised questions over the franchise’s previous conduct. Former Astros beat writer Evan Drellich, who now writes for The Athletic, said the club tried to get him bounced when he worked for the Houston Chronicle.

“They were literally trying to get me replaced on the beat. They wanted me gone. They thought I was too critical… Anything in the playbook you could think of. It didn’t work. The editors stood behind me,” said Drellich. “But there was always the strong sense they wanted to control everything. In college sports, that’s how it is all the time.”

During Drellich’s time covering the Astros from 2013 to 2016, reporters couldn’t talk to team coaches on the record without the approval of the media relations department. At one point, team owner Jim Crane stopped talking to him, according to Drellich. Finally, the Astros had a sit-down with his editors at the Houston Chronicle.

Gene Dias, the Astros’ vice president of media relations, could not be reached for comment for this story.

Chandler Rome, current Astros beat writer at the Houston Chronicle, confirmed reporters need permission to interview team coaches. In his two years on the beat, he’s only interviewed Astros coaches (like famed pitching coach Brent Strom) three times.

READ MORE: Take Me Out To The Non-Ballgame

While Rome’s never gotten the Fenech/Drellich treatment, the Astros can be an “unnecessarily difficult team to cover,” he said.

The former college football reporter should know. He previously covered Nick Saban and the University of Alabama as well as the football program at his alma mater of LSU.

A typical Saban press conference, according to Rome, saw reporters sitting at desks like schoolchildren. They were each allowed a single question. Given Saban’s Bill Belichick-like brevity, the Crimson Tide coach could answer five or six questions and be gone within seven or eight minutes.

“There are times when I’m covering the Astros where I feel like I’m covering a college team as far as access goes and restrictions and things like that,” Rome said.

Media members in these situations are between a rock and a hard place, noted Drellich. Reporters are trained not to make themselves the story. They worry they’ll be blamed by other media members if a player/manager/coach refuses to talk while they’re in the room. They either knuckle under – and hope the problem goes away. Or become the story themselves.

As Drellich put it: “You are not the news. You’re supposed to cover the news. If you then present something dealing with yourself as the news, you are doing something wrong. But I think that understanding, that arrangement, which is born out of a good idea, is being leveraged, essentially. They know that you don’t want to be a trouble-maker.”

Take the Astros’ response to the Fenech incident. The team admitted zero wrongdoing. Instead, it blamed the reporter for the events of Aug. 21st.

“This course of action was taken after taking into consideration the past history between Fenech and (Verlander), Verlander’s legitimate concerns about past interactions with Fenech, and the best interests of the other media members working the game,” said the team in a statement.

“We chose to prioritize these factors when making this decision. Fenech was allowed access to the clubhouse shortly after other media members and had the opportunity to approach Verlander or any player he needed. We believe that our course of action in this isolated case was appropriate.”

The Astros are right: Fenech was eventually let into the clubhouse. But only after Verlander, who spent 13 seasons with the Tigers, finished his media session. And when Fenech approached Verlander, the Astros ace refused to answer his questions.

The former Cy Young Award winner and 2017 World Series champion took to Twitter to defend himself, accusing Fenech of “unethical behavior in the past.” Verlander also tweeted he’d reached out to the Detroit Free Press to give them the opportunity to send another reporter, to no avail.

Asked for his take on the incident, Stark didn’t mince words. The Astros’ behavior was “uncalled for and unnecessary,” he said. But that one incident isn’t representative of his dealings with the team over the years. In fact, Stark called the Astros one of his “favorite” clubs to cover.

“Now I recognize that I’m not a beat writer. I’m a national writer. I’m not as likely to run into the sorts of day-to-day issues that a beat writer might with a player he or she deals with repeatedly in many different settings. But I find their players — including Justin Verlander — to be professional, thoughtful and available, win or lose. I think their manager, A.J. Hinch, is one of the best managers in the sport to talk to. I like talking to (president) Jeff Luhnow and their front office. I’ve known Gene Dias, their media-relations director, for years and I’ve found Gene to be professional and very helpful.”

Forget about beat writers going to the court of public opinion for support, said Drellich. That doesn’t work either. Many sports fans see the press as trouble-making, ungrateful freeloaders. When Drellich waded into the Fenech affair with his tweets about the Astros, he was derided as a crybaby.

“Interesting how we never heard of this before now,” countered one critic on Twitter. “Not a fan of the Astros but you’re just butt-hurt.”

READ MORE: London Calling: Why MLB Is Finally Invading Europe

The bigger issue, warned Drellich, is sports organizations increasingly want to control the narrative. Rather than facilitating access, some media relations departments act more like corporate bodyguards.

“Media relations, in a perfect world, are people who act like people. What that means to me is being reasonable and logical,” said Drellich. “A lot of times, I see people acting like unabashed company men and women with no pretense of right and wrong. Or anything in between. It’s simply whatever they think is best for the company.”