Alabama’s matchup against Georgia in September promised to be one of the biggest of the season, with a packed crowd in Bryant-Denny Stadium, a prime-time slot on ABC, and a visit from ESPN’s College GameDay. Donald Trump wanted in on the pageantry.

The former president arrived in Tuscaloosa well after kickoff, and left long before the Crimson Tide beat the Bulldogs 41–34. But during his stay, he handed out hot dogs to fans, and then retreated to a crowded suite filled with supporters including Alabama Republican senators Tommy Tuberville (a former SEC head coach with tenures at Ole Miss and Auburn) and Katie Britt. At one point, his presence was announced in the stadium.

Kamala Harris wanted to make her mark on the matchup as well. During the game, her campaign debuted an ad attacking Trump for refusing a second debate. The 30-second spot opened with shots of football players practicing and running out of a tunnel. (The campaign also purchased a plane to fly a banner over the stadium reading “Trump’s Punting on 2nd Debate” that night, according to The Washington Post, though the flight couldn’t take off because of weather issues.)

In addition to the Georgia-Alabama spectacle, both candidates have flooded the airwaves with campaign ads on college football Saturdays. Trump and Harris received a larger portion of overall impressions from college football than any other sport except the NFL, according to data shared with Front Office Sports from iSpot.tv, which tracks political ads. (The data provided to FOS counted linear household advertising on national broadcasts, but not local broadcasts or streaming services.)

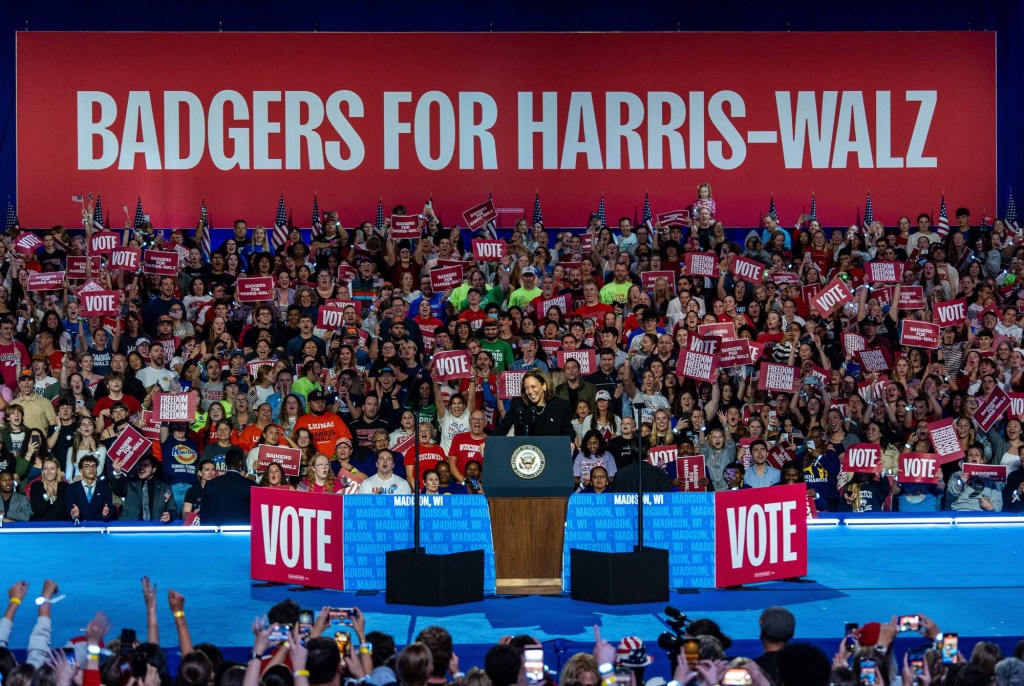

In the final stretch of the election, the polls show a razor-thin margin going into Nov. 5, suggesting both presidential candidates need to utilize every possible avenue to sway voters. Given that so many of college football’s biggest teams and matchups involve battleground states, the sport has become a strategic platform in this election cycle.

The candidates know there’s a platform in sports, and that it’s become increasingly important in close elections. Sporting events provide more reach than any other major television category save local evening news and movies, according to Nielsen data. The Trump and Harris campaigns have received a higher percentage of ad impressions during this college football season than the Trump and Clinton campaigns did in 2016, according to iSpot.tv.

“In a world where people consume TV on streaming services on what I call ‘prime time on demand,’ live sports is one of the last ways to reach audiences in real time,” Jackie Huelbig, VP of candidates and causes at Basis Technologies, tells FOS. “Audiences/voters also tend to be more engaged while watching live sports—which is important leading up to election day with get-out-the-vote messaging.”

NFL games provide more eyeballs, but college football provides access to a more targeted demographic, one industry expert tells FOS. College football, specifically, offers a strategic opportunity for presidential candidates and the PACs that support them: Many of the most popular schools are located in swing states, and many rivalries remain regional despite conference realignment. This provides candidates with access to a large number of viewers likely residing (and voting) in the swing states they’re hoping to target.

Another expert notes that connecting with male voters is important—and college football is a way to reach them. It’s always been a target demographic for Trump; Harris recently made a push courting male voters. The Harris campaign has, in general, put more resources into political ads than the Trump campaign.

The candidates’ official campaigns have targeted games on every major network, including ABC, ESPN, Fox, and NBC. Conference network-specific games aired political ads, too, as did those on The CW (a relative newcomer to FBS football with Mountain West and ACC games). They hammered games with teams from swing states: Michigan, Wisconsin, Nevada, Arizona, North Carolina, Georgia, and, of course, Pennsylvania. Of the 136 ads counted by iSpot.tv, fewer than 20 aired during games featuring teams from other states. In many cases, like with last week’s Michigan vs. Michigan State game, candidates ran dueling ads (Harris bought five, and Trump bought two).

Between Week 1 and Week 9, Harris’s campaign purchased 76 airings, while Trump’s campaign purchased 60, iSpot.tv’s data shows. Harris and Trump spent just $1.45 million and $1.23 million on ads, respectively, but they raked in hundreds of millions of impressions: The Harris campaign received 153.1 million household TV ad impressions, while the Trump campaign got 126.2 million. Both ramped up ads in mid-October, with 40% of Trump’s ads being aired between Weeks 8 and 9, and 18% of Harris’s coming during Week 9 alone.

Overall, the purchases contributed to about a fifth of the candidates’ total impressions during that time period. Trump received 15.8% of his impressions from college football games, while Harris received 4.85%.

In recent weeks, Trump’s campaign ads have focused on one issue: transgender athletes competing in women’s sports. Trump ran the ad 23 times during college football games nationwide. It’s a continuation of anti-trans rhetoric Trump has recently espoused: During a campaign rally in mid-October, Trump referenced the San Jose State volleyball team, which has become the center of media attention on the issue after multiple Mountain West teams forfeited matches seemingly because the Spartans roster includes a transgender athlete.

Trump’s and Harris’s official campaigns weren’t the only ones using the college football platform. Big-name PACs on both sides of the aisle bought ads, too—in some cases, they bought even more than the official campaigns themselves. Make America Great Again, Inc., described by OpenSecrets.com as a “single-candidate super PAC” supporting Trump, bought 137 spots focusing specifically on illegal immigration. Between Weeks 3 and 9, Future Forward USA Action, described as a “Carey committee in support of Kamala Harris,” purchased 109 spots, most recently highlighting Republicans voting for Harris.

While ads reach voters at home, in-person appearances at games enable candidates to connect with the younger student-voter base, which has lower historic turnout than older demographics. The visits almost always generate viral social media content—though not always painting candidates in a positive light.

On the same day that Trump visited Tuscaloosa, VP candidate Tim Walz attended a matchup between Minnesota and Michigan at The Big House in Ann Arbor. Attending a Gophers game would have been natural for the Minnesota governor, but he likely chose an away game at Michigan to capitalize on campaigning efforts.

Walz stopped by a tailgate and posed for photos with students. “I’ve been waiting 60 years to come here,” he was shown saying of his visit to Michigan’s storied stadium. He hugged the Minnesota Gopher mascot, took pictures with cheerleaders, and greeted Gophers coach P.J. Fleck. And, of course, he made sure to post pictures and a compilation of his game-day experience on social media.

But Trump’s supporters took the opportunity to turn the content into a political football: Pro-Trump accounts on X posted a TikTok video of Michigan fans booing Walz, and contrasted it with videos depicting a warm reception to Trump’s at the Georgia-Alabama game.

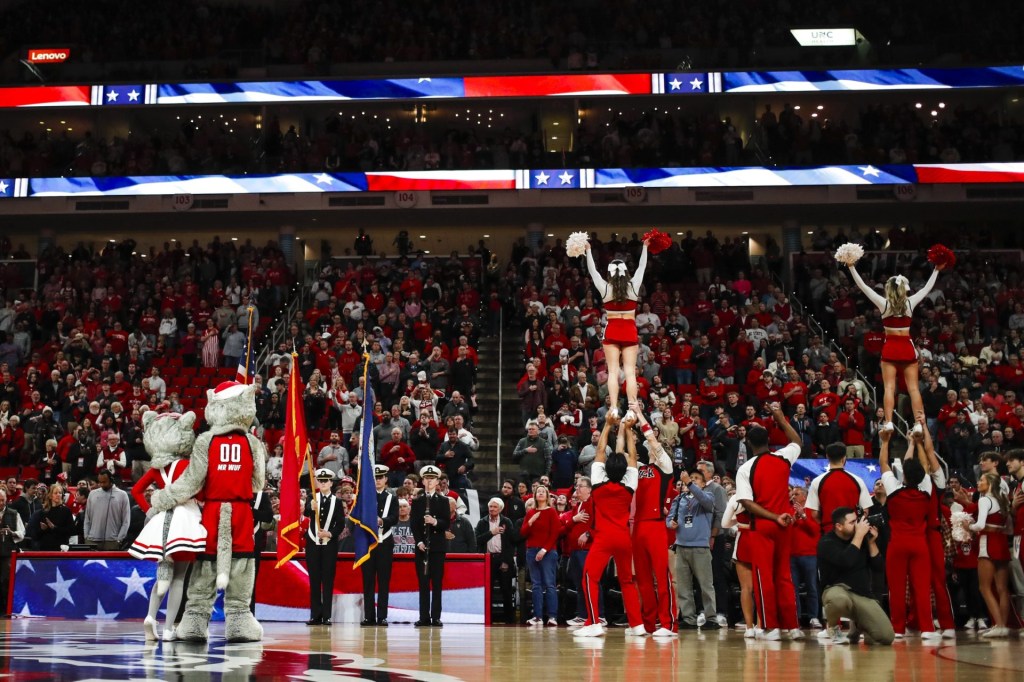

Trump had planned to attend the highly anticipated matchup between No. 3 Penn State and No. 4 Ohio State on Saturday, before canceling his trip. He had already made an appearance on the swing-state campus: During a rally last Saturday at Bryce Jordan Center on Oct. 26, the home of the Nittany Lions’ men’s and women’s basketball teams, Trump brought members of the men’s wrestling team onstage and congratulated them for winning the 2024 NCAA championship.

That day, Penn State’s football team was on the road for a game against Wisconsin. But Trump was still visible to millions of viewers—he and his supporters purchased several ad spots during the game. Harris did, too.

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)