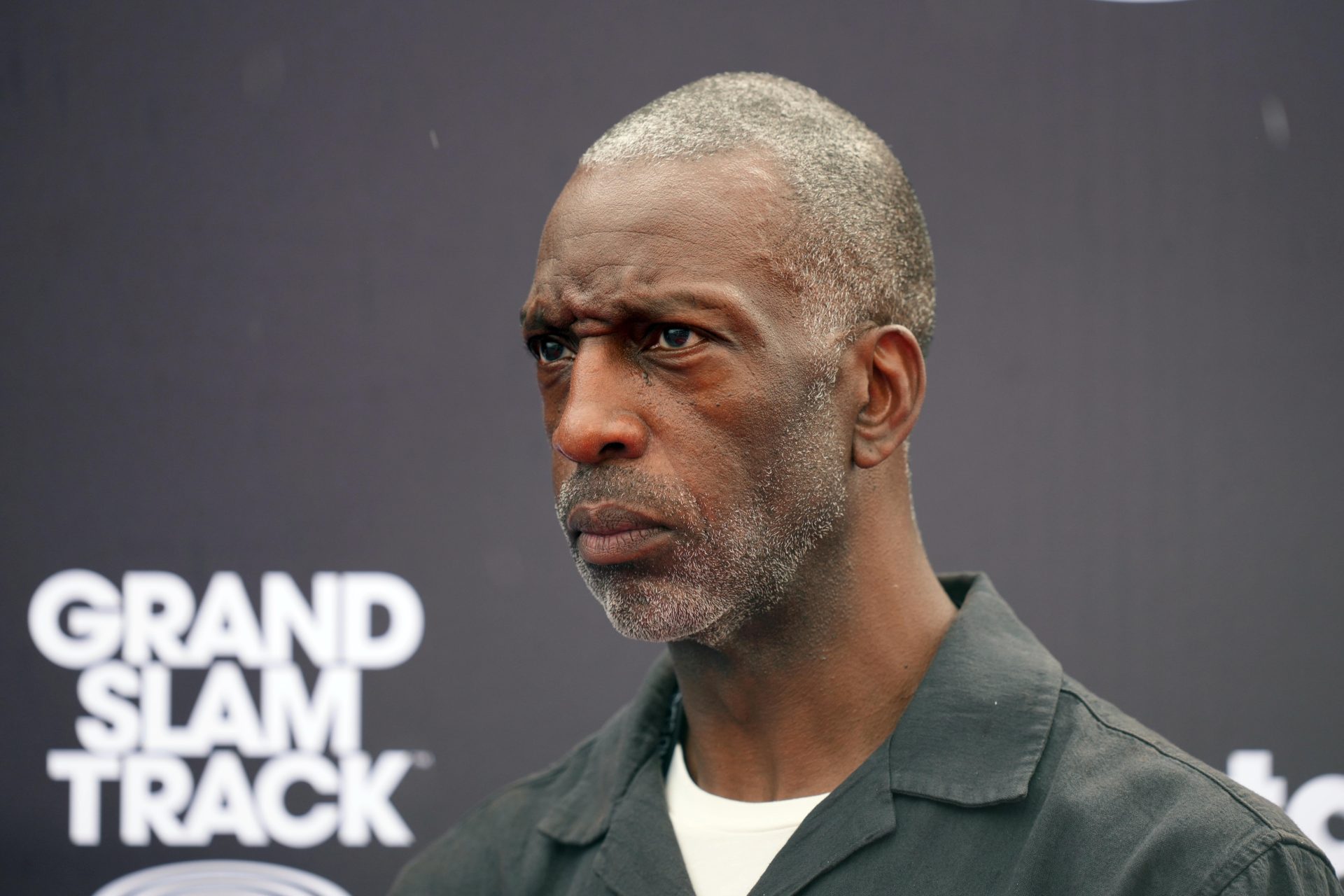

Grand Slam Track is once again teetering on the edge of collapse.

The cash-strapped track league founded by Olympic champion Michael Johnson is struggling to close a deal with roughly 90 vendors it collectively owes about $8 million.

Grand Slam’s lawyers have offered the vendors half of their money back, but a few companies are rejecting the offer, putting the league’s survival in jeopardy.

If this out-of-court settlement doesn’t work, the league may need to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and based on U.S. law, some of the money Grand Slam paid athletes in October could get clawed back.

‘Major, Major Cash Flow Issue’

At its launch, Grand Slam proclaimed it had more than $30 million in funding from investors led by Winners Alliance, the for-profit arm of the Professional Tennis Players Association that is chaired by billionaire hedge fund titan Bill Ackman.

The track start-up that touted its professionalism and historic $12.6 million prize pot had three meets this spring, before abruptly canceling its final Slam in L.A. At the time, sources close to the league insisted financial issues did not force the cancellation, but Johnson later revealed in a July interview with Front Office Sports that an investor dropped out in April, causing a “major, major cash flow issue.”

The Athletic reported in August that the investor who dropped out was Chelsea owner Todd Boehly, who reneged on a signed term sheet for a total of $40 million—and that Grand Slam never actually had $30 million in its coffers.

Earlier this fall, Grand Slam received up to eight figures of emergency financing from existing investors, but it wasn’t enough to cover all of the league’s roughly $19 million in debt to both athletes and vendors. From that lifeline, Grand Slam on Oct. 3 distributed about $5.5 million to athletes, equal to half of what it owed them, then hoped to negotiate debts down with vendors and distribute any remaining funds back to athletes.

On Oct. 31, Grand Slam sent out a letter, obtained by FOS, offering to pay half the debts back to vendors, including event and broadcast production companies, legal and accounting firms, and facilities operators, such as the city of Miramar, Fla., which hosted the Miami Slam. The league owes Miramar $77,896 for using its track.

The letter said Grand Slam is offering to pay back half of total invoices, not outstanding invoices. This means the league would bring vendors up to half of what they’ve ever been owed, rather than repaying half of what it currently owes, which in some cases significantly reduces the payouts.

In the October letter, Grand Slam indicated that if it couldn’t come to terms with creditors, it would need to file for bankruptcy. The letter said that in the event of bankruptcy, there “would not likely be any funds available for unsecured creditors such as yourself.”

The league’s lawyers sent vendors a follow-up letter in November, also obtained by FOS, that said some creditors have supported or agreed to the proposal, some rejected it, and others didn’t respond.

This letter said that repaying 50% of the debt “is the only proposal that GST is able to offer and it is not subject to revision,” and that based on its conversations with creditors, the league is “unable to complete the necessary task” of paying vendors back in full.

The situation intensified last week with news that some vendors already rejected the proposal, namely the sport’s governing body World Athletics.

“We have received a letter from lawyers representing Grand Slam Track and provided them with a reply making it clear that World Athletics would like that the athletes who competed in good faith are paid and treated fairly throughout this process,” a spokesperson for the governing body said in a statement to FOS.

A person close to the league tells FOS that Grand Slam can’t pay any of the vendors “until there is a holistic plan” and the handful of holdouts are “slowing things up.” It’s not clear how many vendors need to accept the settlement for it to go through.

Amid the scramble, Grand Slam’s contract has ended with its former spokesperson, who directed FOS to league president and COO Steve Gera. He did not respond to a request for comment.

Can Grand Slam Survive?

Grand Slam gave vendors a deadline of Dec. 5 to respond to its offer. But two people close to the league tell FOS that the deadline was always soft, and it will get extended a couple of more weeks.

The league is focused on a new timeline to convince vendors to agree to the deal.

U.S. law enables a bankruptcy trustee to collect any payments made to individual creditors within 90 days of a bankruptcy filing and redistribute them to all creditors. Last week, The Times of London reported that because athletes were given partial payments in early October, they could be forced to hand back some of their money, which would then be redistributed to vendors if Grand Slam goes under before January.

“This actually does sound like they’re choosing one group of creditors over another, and if that’s the case, there can be an argument that those moneys should be clawed back for the benefit of all creditors, because it’s unfair that they would’ve been treated preferentially,” Brent Weisenberg, vice chair of the bankruptcy and restructuring department at the law firm Lowenstein Sandler, tells FOS.

The bankruptcy scenario wouldn’t necessarily guarantee more money for vendors than they’d get from the 50% payment, but it could hurt athletes if a trustee indeed claws back some of the money they were paid in October.

“That would of course be tragic,” Paul Doyle, who represents multiple Grand Slam athletes, tells FOS. “I know their intentions were always to take care of the athletes first and foremost, so I believe they will do everything that they can to prevent that from happening. But the situation does look pretty dire. We are all still hoping for the best.”

One person close to the league says that Chapter 11 bankruptcy is on the table. Chapter 11 is a restructuring process aimed at getting a business back on its feet rather than a Chapter 7 full shutdown and liquidation. Another source close to the league says Grand Slam is working to avoid bankruptcy and “definitely trying to stage a comeback.”

Several circumstances might trigger a bankruptcy filing. Grand Slam could file voluntarily to try to cleanse itself of its debt, which might make sense if enough vendors reject their proposal. The league could also decide to file for bankruptcy if any vendors bring a lawsuit against Grand Slam, so that they could address those claims in bankruptcy court. Another riskier, less common scenario would be the creditors filing an involuntary bankruptcy proceeding against the league.

PrimeTime Timing, which timed all three of the Slams, tells FOS it has not received any letter or offer from Grand Slam. Its founder and CEO, Sean Gavigan, says the company has been approached by other vendors about getting involved in a group legal effort.

“At this time I am very hesitant because, as it has been explained to me, positive results for vendors may directly result in adverse scenario for the money the athletes have already received,” Gavigan wrote via email. “While the hardships we have faced have and continue to be quite substantial, it would be against our core company values to do anything that would potentially have a negative impact on the best athletes in the sport we have worked very hard to help build up.”

Winners Alliance is the league’s biggest creditor, one of the people close to the league says. FOS reported in October that Winners Alliance spearheaded the effort to secure the emergency eight-figure financing, and it paid the salaries of Grand Slam’s remaining employees in the weeks that the process unfolded.

Separate from its $13 million investment, the firm is owed millions of dollars in loans, the source says, but does not expect to get its money back unless all other creditors are paid first. (Winners did not exercise its option to invest an additional $19 million, The Athletic reported.) Team Playmaker, a marketing firm owned by Winners Alliance that helped Grand Slam secure a small number of its partnerships, is also independently owed money from the league.

“We believe in the vision of Grand Slam Track, and we’re hopeful that whatever comes next leads to a resolution and the strongest possible future for the league,” a spokesperson for Winners Alliance said in a statement to FOS.

Ackman, who FOS previously reported was supportive but not closely involved in the emergency financing effort, has no obligation to use his own dollars to pay back creditors without some kind of guarantee, bankruptcy attorney Weisenberg points out.

“I think a lot of times you have to explain to creditors that the mere fact that they may have deep-pocket owners doesn’t mean that those owners are going to step up and repay the creditors. They don’t have to,” Weisenberg says.

While Grand Slam’s outlook is bleak, a bankruptcy filing aimed at restructuring doesn’t necessarily signal death. Grand Slam told vendors in its first email it has fielded interest about a potential acquisition.

Athletes have said if Grand Slam does come back, they would want money to be in escrow before they compete to avoid getting burned again.

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jun 15, 2025; Seattle, Washington, USA; Botafogo owner John Textor inside the stadium before the match during a group stage match of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at Lumen Field.](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26465842_168416386_lowres-scaled.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)

![[US, Mexico & Canada customers only] Sep 28, 2025; Bethpage, New York, USA; Team USA's Bryson DeChambeau reacts after hitting his approach on the 15th hole during the singles on the final day of competition for the Ryder Cup at Bethpage Black.](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/USATSI_27197957_168416386_lowres-scaled.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)