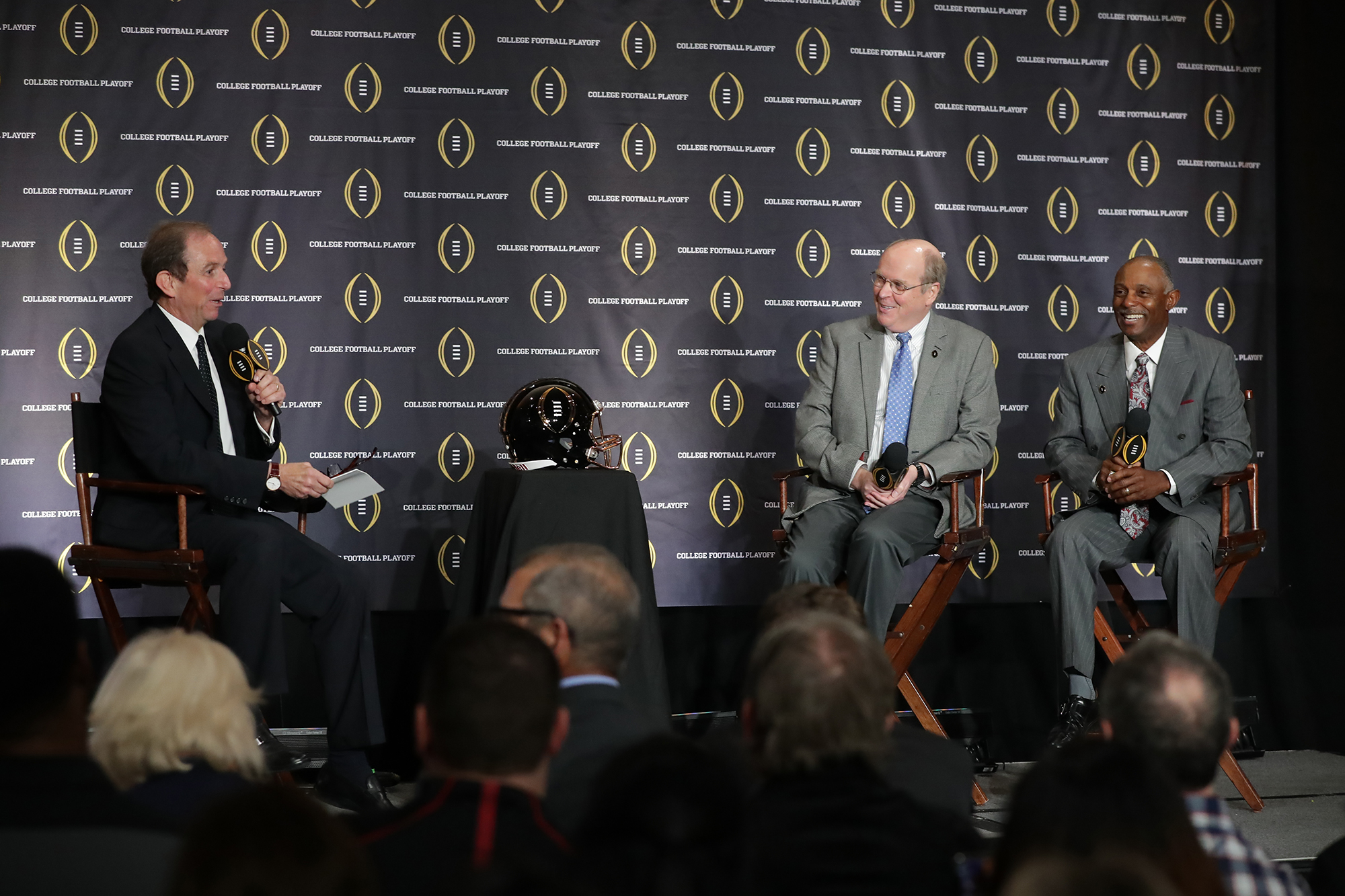

Photo credit: CFP

The number of college football bowl games has more than doubled in the past 30 years.

Originally, they were meant as community-based attractions to bring people to town, like the Rose and Orange bowls, said Wright Waters, the executive director of the Football Bowl Association. As the number of games has exploded — from 19 in 1990 to 40 this year — Waters said the general concept is still the same.

“There is still a benefit to the community,” he said. “It’s like an Olympic city; you’re listed in USA Today every day for at least a month and you’re on TV. Local communities want to be a bowl city.”

While the overall economic impact of each bowl varies greatly — especially as it deviates from the traditional and major bowl games; there were only 11 in 1970 and eight in 1960 — Waters said there are significant benefits for the communities and schools involved.

“I’m OK with the number of bowl games,” Waters said. “The reason we have so many is the benefit of going to a bowl game is so significant.”

READ MORE: Are Bowl Games Really Worth It?

He said spring practice season has become so greatly restricted, the extra three weeks of practice for bowl games is important for the teams. It also provides an extra win for many teams.

“The neat thing is, in the bowl system, half the teams end the year with a win, unlike other championships,” Waters said. “It allows coaches to recruit with ‘We won a game and are on the way up.’”

Waters also pointed to the ability for universities using the bowl games as a fundraising opportunity, and he believes the “Flutie Effect” is real — applications for admission go up with a team’s win on national television.

The surge in bowl game numbers really started in 2000, Waters said, and it was in the ensuing decade ESPN really began pushing Bowl Week — the early slate of bowl games leading into Christmas. Those bowls are great for content fillers and provide the local communities with an event to rally around.

[mc4wp_form id=”8260″]

They, however, have little economic impact, said Bruce Seaman, associate professor in the department of economics at Georgia State University. Seaman regularly studies the economic impact of bowl games and sporting events, especially of those in Georgia State’s home of Atlanta.

Seaman, unlike Waters, is concerned there might be too many bowl games, but jokes with a jovial tone about the subject. With a larger field, the importance of bowl games becomes greatly diluted.

“We have too many; that’s clear,” Seaman said. “At some point we’ll have so many the only criteria will be two wins.”

There is a slew of teams with 6-6 records in bowl games this season, and there have been five teams with 5-7 records in the past 12 years.

“I’m OK with that,” Waters said of the records. “As long as we’re ranking them by academic progress, I’m OK. Isn’t it neat we’re rewarding them for being good students instead of penalizing them?”

READ MORE: Inside the Event Management Playbook for College Football Bowl Games

It also keeps the end of the regular season competitive for more teams, Waters said.

“I’m old enough to remember when we didn’t have but 20 bowls,” he said. “Now, it’s the last week of the season and teams are jockeying for their sixth win or getting to seven because it improves their bowl outlook.”

If teams start to decline their bowl invitations, then the bowl season might start to look different — but for now, Waters said the communities across the country will continue to want to host and teams will want to play.

“We rarely hear a team that qualifies say, ‘We don’t want to go,’” Waters said. “Teams and universities want to be on national TV, and it’s important to make the numbers work, but there are different ways to do that.”