Sports investment has turned from a passion project to asset class in recent years. The financial evolution is moving at a rapid pace, with franchise valuations skyrocketing, ownership structures shifting, and new leagues emerging—from women’s soccer to start-up combat sports.

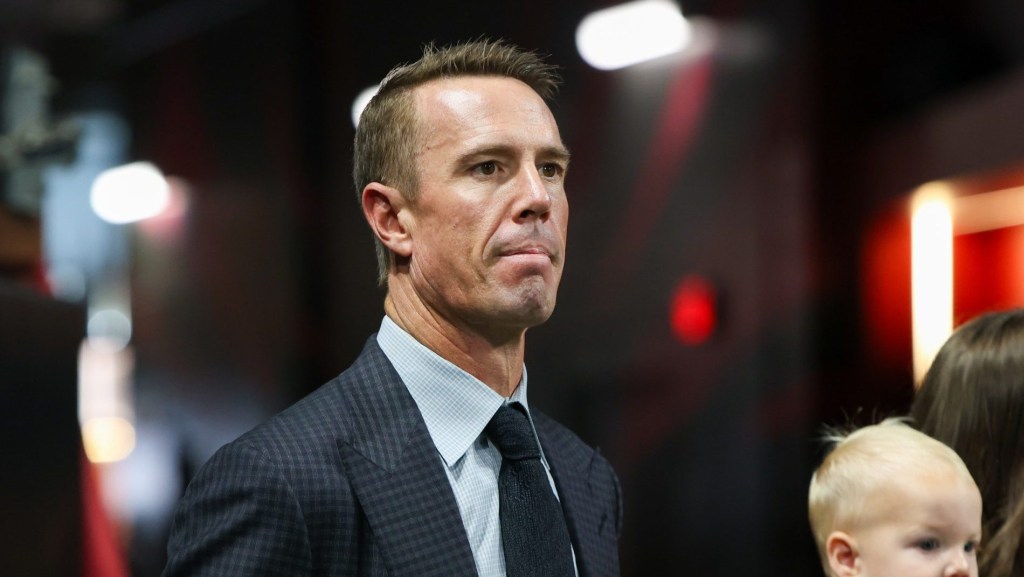

Behind the headlines is a nuanced story about supply, demand, risk, and return. To make sense of it all, Front Office Sports spoke to two executives in the sports industry group at Citi—John Hutcheson and Ivo Voynov, who lead Citi’s sports advisory and financing group—which has worked on all kinds of deals, from advising the NHL amid the Diamond Sports bankruptcy to counseling the Pittsburgh Penguins on their sale to Fenway Sports Group and guiding the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia on its acquisition of Newcastle United.

They broke down why valuations are soaring, how pandemic-era resilience showed the staying power of sports, and more.

Front Office Sports: What’s going on with the rise in pro franchise valuations? Why are they hitting such insane heights? Why now?

John Hutcheson: Sports is an area that’s near and dear and tangible to investors, which means there’s also been a level of focus and familiarity with it. The other piece is that the owners of sports assets have the potential to do really well from a financial perspective. Many ownership groups had largely been sort of “mom and pop” that were successful business owners who then transitioned to team ownership. And then over time those sports franchises became a significant proportion of their overall wealth. So many have done really well, and money often follows success.

If you look at team valuations in recent years, they’ve mostly been up and to the right. It’s a combination of fundamental business performance, including growing revenues on the back of media-rights renewals and hospitality and sponsorship sales. It’s a supply/demand equation. There have been more billionaires created over the past 10 years than there were the prior 20, inflation-adjusted. So you have a supply/demand imbalance that’s also driving it.

Ivo Voynov: In terms of your question on timing—why now?—I think [the COVID-19 pandemic] also had a lot to do with it. It was such an impactful event, and sports was one of the sectors most affected. You had no fans in the stands, yet no team went through bankruptcy; no league was downgraded from investment grade. In fact, quite the opposite. You saw record valuations, for example, with the Mets in 2020. Then the Broncos, then the Suns, Commanders. All these deals were done at new all-time highs in the middle of, or immediately after, what was supposed to be this huge disruption. The sector showed it was able to sustain, and I think that opened up broader investor appetite.

FOS: Not only are valuations on the rise, but new leagues keep popping up. Is it all the same capital being poured into sports?

JH: It’s a question that comes up frequently: Are we in a period of peak sports? People raise it because you’re seeing all these leagues pop up. There’s three women’s volleyball leagues, and there are multiple MMA leagues. I think if you take a step back, this is the North Star. There’s huge value if you get the league right and you’re able to create your own, wholly owned league while owning and controlling it top to bottom. Look at Formula One and UFC.

There’s a natural gravitation to try things again that previously worked, to find the next area where you can create something that’s so successful where you own the IP. So that’s the North Star I think many investors are chasing. There are very few of scale, and it’s rare to get there. There are maybe five or six such leagues that are meaningful in size. So if you get there, you’ve really climbed the mountain.

IV: For a lot of these leagues, the reason they’ve popped up is because the cost of distribution is now basically bid down to zero. You no longer need to be on any of the big networks to provide content to your fans. You can reach them via various forms of technology.

The problem becomes, “How do you create a model where you can mitigate the churn?” Because people now kind of just churn in and out of entertainment on streaming services. The customer acquisition cost remains pretty high, and it’s tough to fight for sponsors in a very crowded space.

FOS: How about women’s sports? You’ve got the WNBA, the NWSL, etc. Women’s sports are clearly having a moment.

IV: On the women’s side, I think people are drawn to this idea that the WNBA and NWSL actually have a clear path to creating the best global league in their respective sports. Leagues like the NBA, MLB, NHL, NFL, have the best product out there. You can see the same path for the NWSL over time, and it’s the same thing for the WNBA. The best players are in this country. So, you can create a closed end league without relegation, where you have the best product for women’s sports.

FOS: The size of groups that are being put together to buy teams are growing. It used to be the George Steinbrenner model: he owns the team, he’s going to own it until he dies, he’s going to pass it down to his kids. That seems to be changing. What is driving these trends of larger ownership groups and more frequent franchise sales?

IV: A big part of this is that valuations have increased dramatically. Meanwhile, the leagues tend to manage how much debt each franchise can incur in an attempt to keep competitive balance across the league. So, as the leagues manage these debt limits conservatively, the equity checks that investors have to write have become pretty big.

And look, while the world keeps printing new billionaires every year, many of them are not liquid. For many, writing a billion or a half-a-billion-dollar check for a deal is hard. So, we are seeing LP [limited partner] groups expand, especially now that they have private equity money too.

It’s also getting harder to raise money because you’re looking at people who have to write a check for $300 million that own only a small percentage of the franchise, and really have no rights. It’s a totally passive investment. They can do okay on it over time, and they’re probably not going to lose money, but it is a sizable check.

FOS: You mentioned private equity, which has been getting deeper into pro sports over the years, including last summer when the NFL voted to approve a policy allowing limited PE investment. Do you see that trend continuing?

IV: The obvious answer for these leagues is that private equity needs to play a bigger role, but the leagues are threading carefully because they need to make sure the PE investment frameworks work as intended.

All these private equity funds ultimately need to generate liquidity for LPs. They need an exit strategy. The biggest question is, what does that look like? In a situation where you own the asset, you can dictate the timing on when you exit, and you can run the process. Here, you can’t really do that. If private equity sports funds are not able to show that they can exit these investments and generate liquidity for their LPs, it’s going to be a harder model to sustain over time.

JH: The exit piece is the riddle that hasn’t been solved. It’s easy to get in, but it’s not yet entirely clear how you get out. Some of that might be what we call “new technology.” There are continuation vehicles that are funded by pension funds and others that might be on the other side of these types of transactions someday. Continuation funds are certainly used in private equity, but I haven’t seen it used on the sports side yet. But we do hear people talk about it as a potential exit path in the future.