There are less than a thousand words laying out the process the NFL has never used: the removal of one of its owners.

While there have been indications that Washington Commanders owner Dan Snyder could be the first, it’s not as straightforward as just taking a vote to yank a franchise for conduct detrimental to the league.

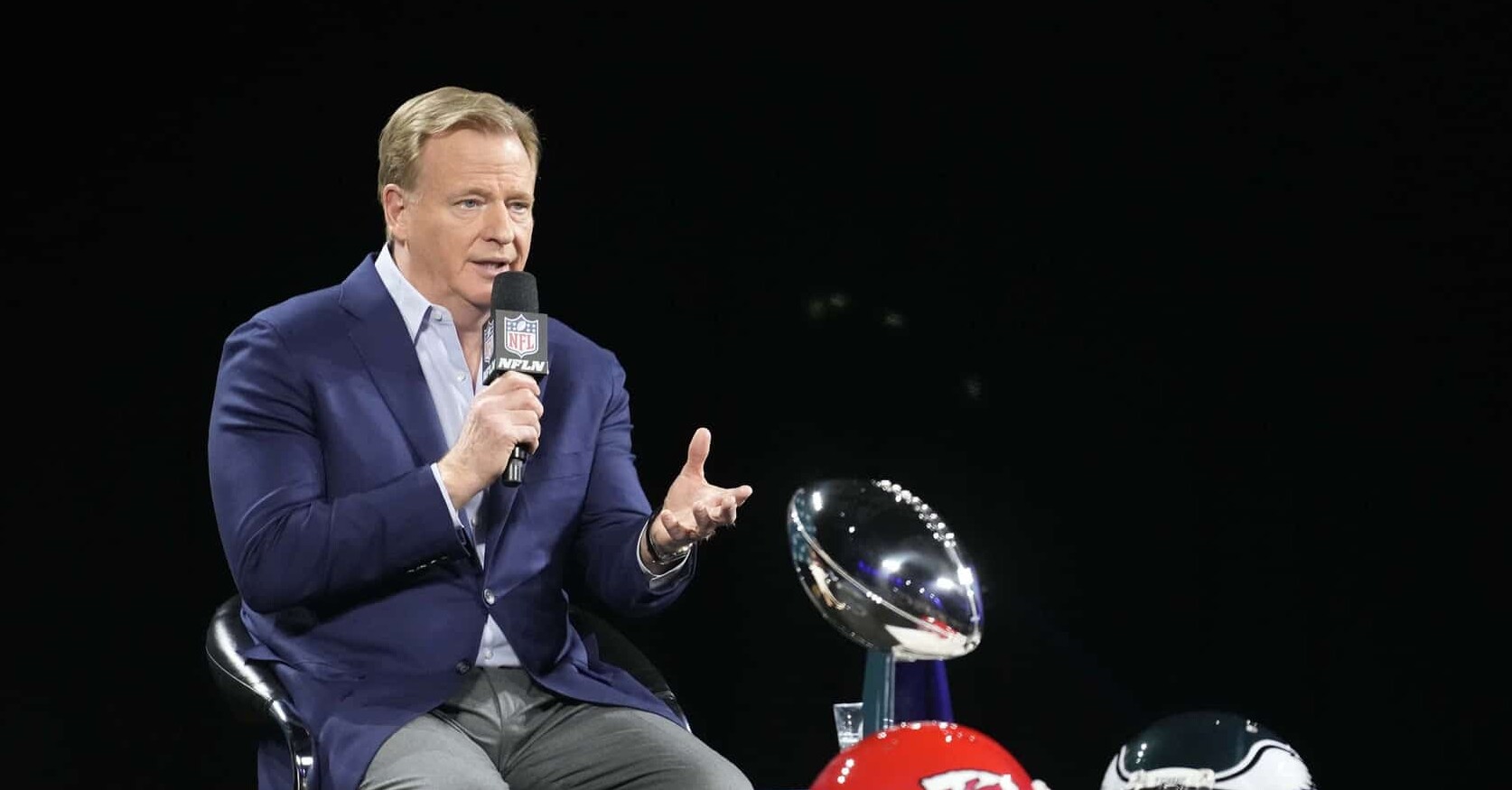

For the process laid out in the NFL’s Constitution and Bylaws to even start, Commissioner Roger Goodell or one of the owners would have to submit “charges” against one of their own. Goodell then would conduct an investigation “as he deems appropriate” and “make his recommendation thereon to the member clubs.”

The male-centric wording hints at how long ago this section of the NFL Constitution was written, which predates Georgia Frontiere becoming the first woman controlling owner in 1979 when her husband, Carroll Rosenbloom, drowned off the coast of Florida.

“The imprecise language leaves much to be desired,” sports law attorney Dan Wallach said. “The ambiguous wording could understandably lead to a concern that the procedures are so amorphous and poorly defined that the league could be subject to legal challenges.”

The league didn’t get far down the road on other owners accused of misconduct.

- Jerry Richardson, who owned the Carolina Panthers for 23 years and passed away last week at age 86, chose to sell his franchise before any movement toward removal had a chance to start. Richardson began the sales process after Sports Illustrated published allegations of sexual harassment and the use of a racial slur in December 2017.

- Eddie DeBartolo pleaded guilty in 1998 to a felony charge for concealing a $400,000 payment to Louisiana’s former governor in a bid to obtain a casino license for one of his businesses. His sister, Denise DeBartolo York, took over the San Francisco 49ers on an interim basis, and — after a court battle — an agreement was reached in 2000 that left DeBartolo York as the full owner going forward.

- Art Modell (financial struggles) and Jim Irsay (driving under the influence) are among other owners who have also managed to avoid the removal process.

“The real reason these procedures have never been invoked is that there’s never been anybody quite like Dan Snyder,” said Wallach, co-host of the Conduct Detrimental podcast. “This is the only owner who chooses to fight.”

Owners Would Be Jurors

The clock starts after a charge against an owner is introduced. Within 15 days, the owner has to submit a response. Once that response is in (or the 15 days are up), Goodell would schedule a special meeting akin to a trial or arbitration.

The owners are the jurors, and Goodell is the judge as evidence is presented. Goodell could designate somebody else to preside over the special meeting — and he would have to if he was the one to bring the charges and not one of the owners.

According to the NFL Constitution, “strict rules of evidence shall not apply, and any testimony and documentary evidence submitted to the hearing shall be received and considered.” There’s no time limit laid out in the league’s rules, and there isn’t a standard for burden of proof either.

In civil cases, there’s the preponderance of the evidence standard.

“That is described in public civil litigation as a 51% standard,” said Jodi S. Balsam, a Brooklyn Law School professor, and former NFL attorney. “You just have to believe it’s more likely than not — it’s not a reasonable doubt standard used in criminal trials.

“But there’s an intermediate standard that you find in some civil settings of ‘clear and convincing evidence.’ That parks it somewhere between the 51% [in civil courts] and the north of 90% reasonable doubt standard for criminal trials.”

Balsam added there’s no way to tell which standard the NFL would use in such a process.

“The clear and convincing evidence standard is often used when a civil matter presents a particularly harsh remedy,” she said.

And with NFL franchises valued up to $8 billion, ripping a team would seem harsh.

Removal Requires 24 Votes

At least 24 owners (three-fourths of the 32 teams) would have to vote in favor of removal, and there’s little recourse — at least in the NFL Constitution — for the removed owner. Besides removal, that charged owner could be suspended instead.

The owner “agrees to release and waive any and all claims that such party may now or hereafter” after the decision against the commissioner, any league employee, and all the other owners.

That legal language is meant to thwart a legal challenge by the ousted owner.

NFL players who run afoul of the league’s personal conduct policy have challenged the league’s authority.

The NFL Players Association was successful in federal court — at least for several weeks — that delayed the suspensions of Tom Brady (Deflategate) in 2015 and Ezekiel Elliott (domestic violence allegations) in 2017.

But ultimately, those cases were compelled to arbitration as Goodell’s authority as a commissioner was upheld. Brady and Elliott eventually served their suspensions.

After a lawsuit by this hypothetical embattled owner, the NFL would likely argue that owners — like players — are bound by arbitration provisions.

“Just because arbitration provisions exist doesn’t mean the people affected by them won’t be willing to challenge them in court,” Baslam said. “This arbitration provision is arguably weaker than the players. … What makes this different is that this is a non-labor setting.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jun 15, 2025; Seattle, Washington, USA; Botafogo owner John Textor inside the stadium before the match during a group stage match of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at Lumen Field.](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26465842_168416386_lowres-scaled.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)