In the News

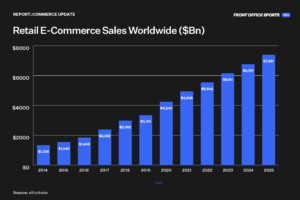

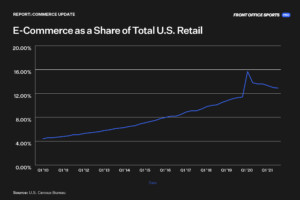

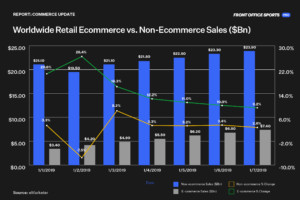

The e-commerce narrative hit a climax in the second quarter of 2020 as the social infrastructure shifted from offline to online. Many posited that the change was a structural one and that commerce was permanently shifting online. Others were more skeptical, believing the behavior was indicative of a historical anomaly rather than a structural change.

Today, the narrative seems to have swung in favor of the skeptics.

Public markets tell a similar story. E-commerce companies’ share prices reached stratospheric levels in 2021, largely influenced by two economic forces: an immobile consumer with large amounts of disposable income and some of the cheapest financing in recent memory. But in 2022, financing is no longer cheap, and consumers have resorted to their old ways — exploring the world of brick-and-mortar stores.

On Tuesday, Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke announced that the company will be laying off 10% of its workforce (roughly 1,000 jobs). The layoffs are a product of Shopify’s realization that one of its key pandemic theses is proving inaccurate. Two years ago, Shopify mistakenly bet that money spent in e-commerce vs. physical retail “would permanently leap ahead by five or even 10 years,” according to Lutke.

Shopify isn’t the only company that believed the change in behavior was a pull forward. A multitude of startups and established companies alike made decisions over the last two years, based on the assumption that consumers had permanently shifted their shopping habits online.

- VC investment in retail and e-commerce technology increased from $46.7 billion in 2020 to $108.6 billion in 2021 according to CB Insights.

- To date, $36.9 billion has been invested in the first half of 2022, projecting a total of $72.9 billion for the year.

But investments aren’t necessarily leading indicators of social or consumer behavior change. It turns out that online shopping may have been more temporary than most retailers initially thought.

On Wednesday, Shopify posted an adjusted quarterly loss per share of $0.03, compared to the $0.03 profit analysts expected, per Bloomberg. The company saw its revenue increase 16% to $1.3 billion from a year ago, in line with expectations of $1.33 billion, while also increasing gross merchandise volume (GMV) 1% to $46.9 billion — nearly $2 billion less than Wall Street’s $48.6 billion estimate.

Retailers like Shopify are not the only ones losing out on the bet on the future of online commerce. Various businesses whose customer trends are directly related to online shopping are also taking a hit.

From payments to banking, the commerce ecosystem is feeling the effects of the return to “offline” shopping. In particular, “buy now pay later” companies have been disproportionately affected. Klarna recently took an 85% valuation cut, Affirm is also struggling as its overall market cap is down 58% year to date, and Zip and Sezzle canceled acquisition plans.

The apparent regression doesn’t mean that e-commerce is going away. The data indicates that rather than a relative decline, we’re observing a regression to the mean for e-commerce volume and behaviors. Online sales are up overall and on track with pre-pandemic projections.

Signs are pointing to consumers returning to brick-and-mortar stores, impacting the share of online sales. According to the Wall Street Journal, investors believe that the reset in valuations is warranted.

“E-commerce is definitely not as sexy as it was a year-and-a-half ago,” said Max El-Sokkary, an analyst at Zevin Asset Management, which owns shares of Amazon and eBay. “The momentum that carried e-commerce during the pandemic has slowed down, and at some point, the valuations on some of these stocks don’t make sense.”

While the current moment feels like doom and gloom, e-commerce companies remain bullish about the prospects of their businesses as technology advances to facilitate online transactions.

Nevertheless, executives in the space say that even as online shopping captures a larger share of consumer spending over time, there are still some elements of the in-person experience that will be difficult for digital to duplicate — a conflict playing out in real-time.

The Case for Brick-and-Mortar

The scale and velocity of e-commerce growth at the onset of the pandemic were astounding. It is estimated that more than 85,000 online stores opened in the first four months of the lockdown. Individual stores that had never considered a digital strategy were forced into e-commerce as a survival mechanism, whether they wanted it or not.

Now, stores are going back to their brick-and-mortar strategies. Traditional online-only retailers are now the ones investing in physical storefronts in order to grow. 2021 saw a doubling of the total number of stores being opened by retailers, including many digitally native brands like Vuori, Fabletics, and Warby Parker according to Shopify.

The reasons for expansion into new physical locations varied. Many of them stemmed from the availability of capital and pressure on property owners to renegotiate leases.

According to data compiled by Shopify, there is increasing demand for in-person shopping experiences. While the desire for “tangible” experiences was exacerbated by the pandemic, the desire isn’t new. A Statista survey indicates that as far back as 2019, 63% of customers were willing to switch to in-store shopping if the experience was improved.

In a LinkedIn post from Ricardo Belmar, Director Partner Marketing for Retail & CPG at Microsoft, he posits that product discovery is one of the reasons for this shift back to brick-and-mortar.

“The acceleration of e-commerce thought to have been driven by the pandemic hasn’t lasted compared to store sales growth. 2021 and 2022 are seeing stores take advantage; partly because consumers want that physical shopping experience they couldn’t get during the pandemic, but also because e-commerce just hasn’t made product discovery as easy as walking down a store aisle or looking at a store display to see something you want to pick up and buy.”

-Ricardo Belmar, Director Partner Marketing at Microsoft

Record high inflation is hurting consumers across the board, but it presents an opportunity for brick and mortar. Until recently, customer acquisition was significantly cheaper for online-based companies. The discrepancy in acquiring customers is now coming down. If brick and mortar can leverage technology to harness in-store data (inventory management, store layout, staffing, etc.) they might be able to continue and close the gap.

The Customer Acquisition Problem

In the shift to online commerce, brands shifted their rent cost to online marketing — the digital equivalent of rent.

In an article published by Shopify, the company lays out the case for why CACs and rents are becoming increasingly comparable.

“As commercial rents are falling by rates even greater than those seen in or after the 2007-2008 Great Recession, Moody’s Analytics estimates that effective retail rents will fall 11.1% — nearly twice the drop that retail rents saw following the Great Recession”

Digital rents are now expensive. In fact, they are expensive enough that brands have to consider the tradeoff between paying rents in the real world and online. Where the digital arbitrage was once undeniable, there is now more of a question.

Over the last five years, there is a pronounced difference in the cost of marketing online. The average CAC for a sample of 700 subscription-based e-commerce businesses is up 60%. And where does this cost manifest itself? Advertising.

The average cost-per-click for Facebook advertising has grown from $0.7 in 2018 to $2.25 in 2021, according to data compiled by Statista.

Then there’s the regulatory pressure being felt by digital advertisers. The rules have changed, and not just in the U.S. Since the introduction of GDPR in Europe in 2016 and data-regulation rules like CCPA in the U.S in 2018, privacy has become increasingly important and complicated. In essence, the world’s largest tech companies are now required to update their privacy rules. The result: positive outcomes for consumers but a nightmare for digital marketers that use those platforms.

Examples of the changes can be seen most prominently in both Apple’s and Google’s new privacy updates.

The most famous example is Apple’s iOS 14.5 update in 2021. The update changed the way mobile applications track user data writ large. Under the new rules, users now need to opt-in for apps to have the ability to track their behavior. According to initial reports, only 21% of users opt-in, on average.

Google, meanwhile, announced the phase-out of Chrome’s third-party cookies. When the change is fully implemented in 2023, ad personalization and ROI will fall further and raise CACs for companies in the e-commerce space due to an inability to target and create shadow audiences.

E-commerce will always be an important asset to brands, and as a trend, it is still growing. The euphoric phase, however, seems to be over.