Don’t look now, but ESPN isn’t as irrelevant as may you think.

It’s no secret that TV networks have been scrambling: with the rise of streaming services such as Netflix, ratings have depreciated significantly.

Netflix and Disney

Though Netflix has become the ubiquitous streaming service (with a 75 percent market share), it remains to be seen whether its firm hold will last. Up to this point, Netflix’s success has been driven by their ability to produce highly engaging original content — distinguishing themselves from most of their competitors, save HBO.¹

However, most recently, in a much-publicized move, Disney ended their distribution contract with Netflix, with the intention of developing their own streaming service. This isn’t as bad for Netflix because they are losing content, but because they may be gaining a major competitor.

Remember when we talked about Netflix’s great original content? The Walt Disney Company is the original content king. Their IP and associated properties are virtually unmatched, and through that, they have become the second-largest media conglomerate in the world (after Comcast). With that said, if Disney does enter the streaming industry, we can expect individual firm profits to dip as competition grows.

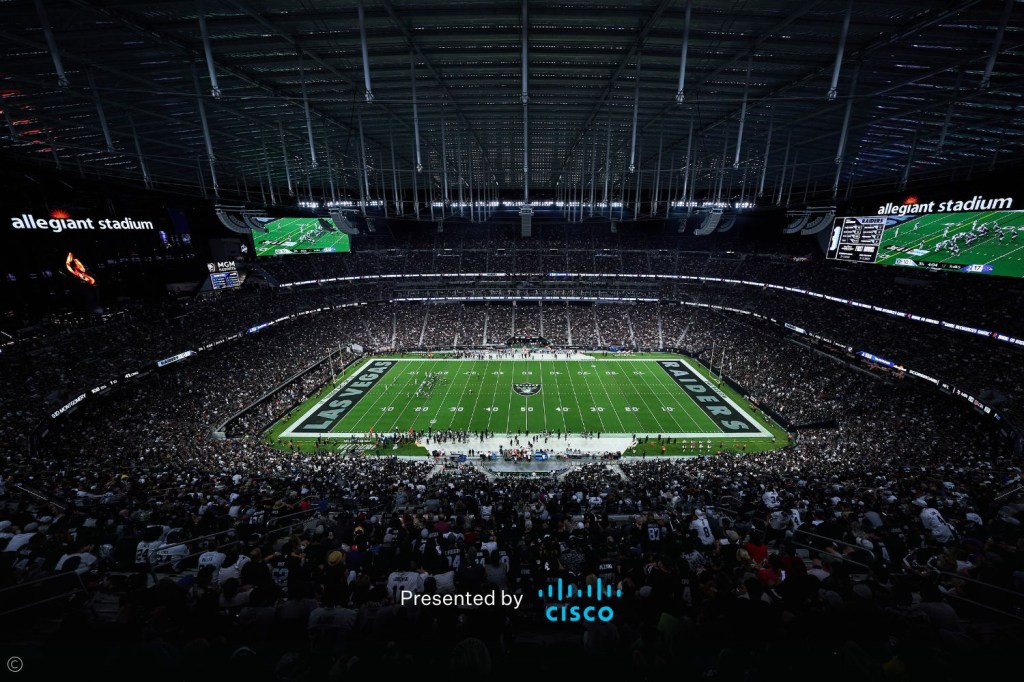

Disney also owns ESPN, which holds the keys to something that Netflix will have no way of competing against in the short term: sports broadcasting rights.

ESPN currently has long-term broadcasting rights in place for the NBA, the MLB, and the NFL — three out of the four major sports leagues in North America. And in addition, they still have the rights for most of the college post-season bowl games.

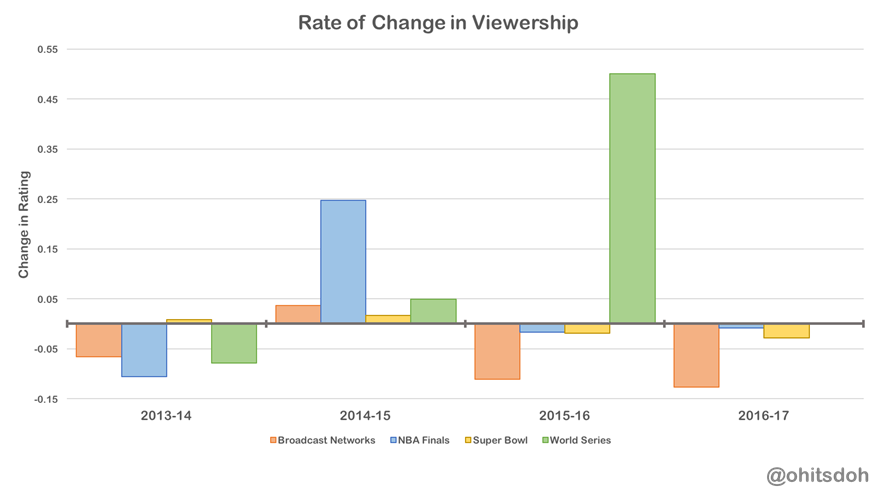

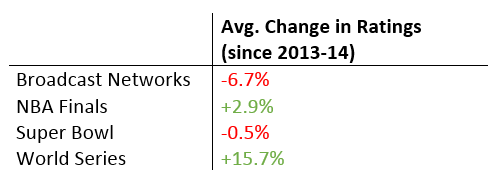

On TV, their ratings have held relatively steady. Compare these to the broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, CW, Fox, and NBC):

In the short-term future, we should continue to expect greater slippage for non-sports broadcasting, relative to live sports. Users have fewer options when it comes to live viewership, meaning that users are relatively inelastic when it comes to their attention.

Still, all broadcasting suffers as a result of streaming services like Netflix: consumers have a limited amount of attention, and the more options there are to deviate away from cable, the lower the opportunity cost of cutting the cord.

However, sports is differentiated in a cable bundle because they are: a) repeated live events (making piracy more difficult), and b) a sticky product (once you’re a fan, it’s harder leave the sport). This leads to their relative stability.

Another thing in ESPN’s favor: sports is uniquely suited for digital distribution, given its pure volume. Fans of niche sports (see: Ultimate) previously did not have access to live broadcasts in a cable bundle, since content was bound by time constraints. A live streaming service has infinite capacity — any number of events can be broadcast at any given time.

New Faces: Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube

The lurking giants in the live streaming industry are the usual suspects: Amazon, Twitter, and Facebook. For each company, obtaining sports broadcasting rights accomplishes different core goals — for Amazon, it will be to drive Prime Memberships (pay-to-access), and for Twitter and Facebook, it will be to drive engagement, and therefore advertising revenue.

Here’s the list of major live streaming partnerships by each company, with their broadcast partners in brackets:

Maybe you noticed — but exactly zero of these companies can broadcast a show on their own.

That’s why, last week, Disney purchased a $1.58B stake in MLB’s BAMTech. BAMTech came from MLB Advanced Media, and has been considered one of the top streaming services in the world.

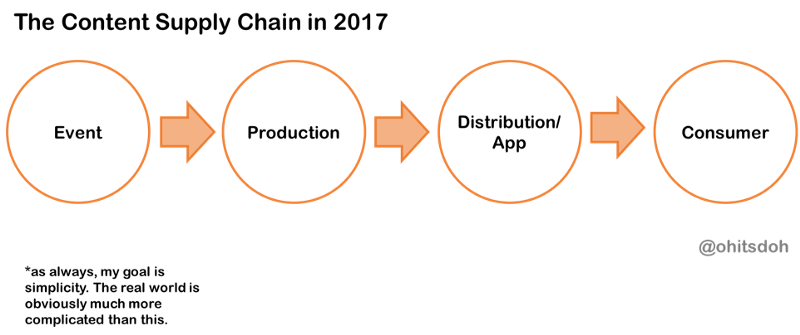

As a result, ESPN is now uniquely positioned to own large parts of the digital content supply chain — from production, to distribution.

This integrated supply chain means that ESPN will have flexibility that no other company will be able to offer. They will also be able to tackle inefficiencies, leading to potentially higher profit margins.

In the past, ESPN had only played a major role on the production end. The BAMTech purchase provides ESPN with the opportunity to play as distributors in a digital age — a completely new dimension that they otherwise would not have been familiar with.

On an upgraded ESPN app, Robert Iger (CEO of the Walt Disney Company) said the following in their most recent earnings call (crucial parts in bold):

“You can use it as an authenticated subscriber of a multichannel service, which basically gives you access to the direct, to the streams of the ESPN channels, or you can buy up or buy additional sports products through the subscription, but again, it’s the same seamless experience. And there’ll be upsell opportunities for us as well. So you’ll watch a highlight, if you want to buy maybe part of a game that’s going on live, if you want to buy that game, you’ll be able to buy it directly through the app or subscribe to the service directly through the app. It’s basically a one-stop shopping for the consumer and it’s one-stop shopping for us in terms of our ability to manage the consumer that wants to consume sports through ESPN.”

Which is pretty monumental — in addition to the bundle offering you multiple channels, the individual channels also bundle specific television programs together for the customer. If the new ESPN app does indeed provide coverage of individual events as a la carte content, we will be seeing the further disintegration of the cable bundle.

The Bundle — Today and Tomorrow

But with all this talk about the cable bundle and the ire associated with providers, it is important to analyze whether purchasing individual streaming services would be more valuable than bundles.

The cable bundle, in simple terms, can be explained by the following:

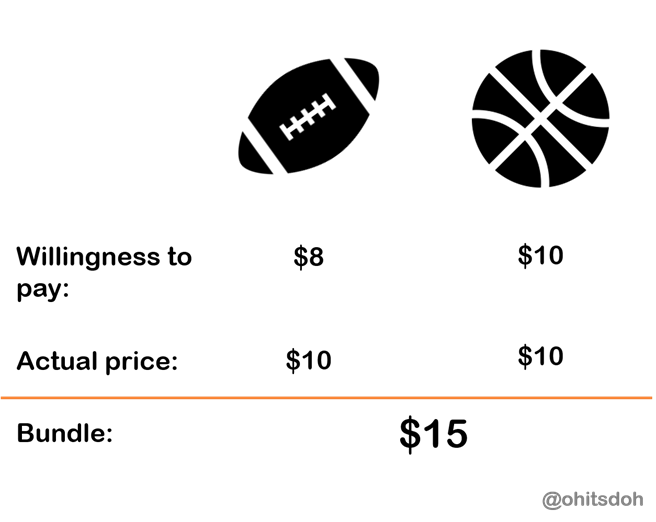

If my willingness to pay for a football is only $8, but my willingness to pay for a basketball is $10, when the cost of both is $10, I would only purchase the basketball.

However, if they were both sold as a bundle for $15, I would be willing to purchase both, since my consumer surplus of purchasing the bundle (willingness to pay minus actual price) is now $3. On the other end, the seller would also benefit, since they would be gaining $5 in additional revenue.

This is the same logic that cable providers follow! Bundling will generally result in a consumer-friendly outcome, and considering low marginal costs and unlimited supply², sellers will also benefit. Therefore, in the long run, with multiple streaming services, we should NOT expect consumers to be better off, since their consumer surplus will likely decrease or stay the same.

But it probably does not end there. This also leaves space in the industry for an aggregator to consolidate streaming services in bundles — playing the same role that the cable companies are already playing. Where networks had formerly provided the content for cable companies to distribute, streaming services now take their place.

In my opinion, this is where Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube may pose the greatest threat — not by working as a competitor to Netflix, ESPN, Disney, or any other streaming service, but as an aggregator, working in partnership with the streaming services.

Front Office Sports is a leading multi-platform publication and industry resource that covers the intersection of business and sports.

Want to learn more, or have a story featured about you or your organization? Contact us today.

¹ Netflix’s current business model is actually extremely similar to HBO’s — subscription services, driven by premium original content. ^

² Important because opportunity costs need to be considered. ^

![[US, Mexico & Canada customers only] Jan 25, 2026; Taipei, TAIWAN; Alex Honnold free solo climbs Taipei 101.](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/USATSI_28081468_168416387_lowres-scaled.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)