Justine Siegal has a vision for the women’s pro game. Full stadiums, high-caliber athletes, and franchises across the country.

“Once there’s a pro baseball league for women, it will help show that there is a pipeline from T-ball all the way up,” Siegal, who is the first woman to coach in any capacity for a Major League Baseball team, told Front Office Sports. “No longer will girls have to hear there’s no future for them in baseball.”

That’s why she and Toronto businessman Keith Stein have plans to launch the Women’s Professional Baseball League (WPBL) in 2026. This spring, the WPBL will host a scouting camp for interested athletes with the intention of holding a draft in the fall. And then next summer, a six-team league will play a 40-game season. If it succeeds, it will be the first pro baseball league for women since the immortalized All-American Girls Professional Baseball League of the World War II era.

In an era of upstart sports leagues, it has an even more lofty goal than most: codify baseball as a true women’s sport.

“Women have been playing baseball since before they had a right to vote. They make up over 40% of MLB fans. Team USA is ranked second in the world, and girls’ baseball is on the rise,” Siegal says. According to MLB, 46% of the league’s fans are women, and 53% of women consider themselves MLB fans. “Seems like a perfect time to start a women’s pro baseball league.”

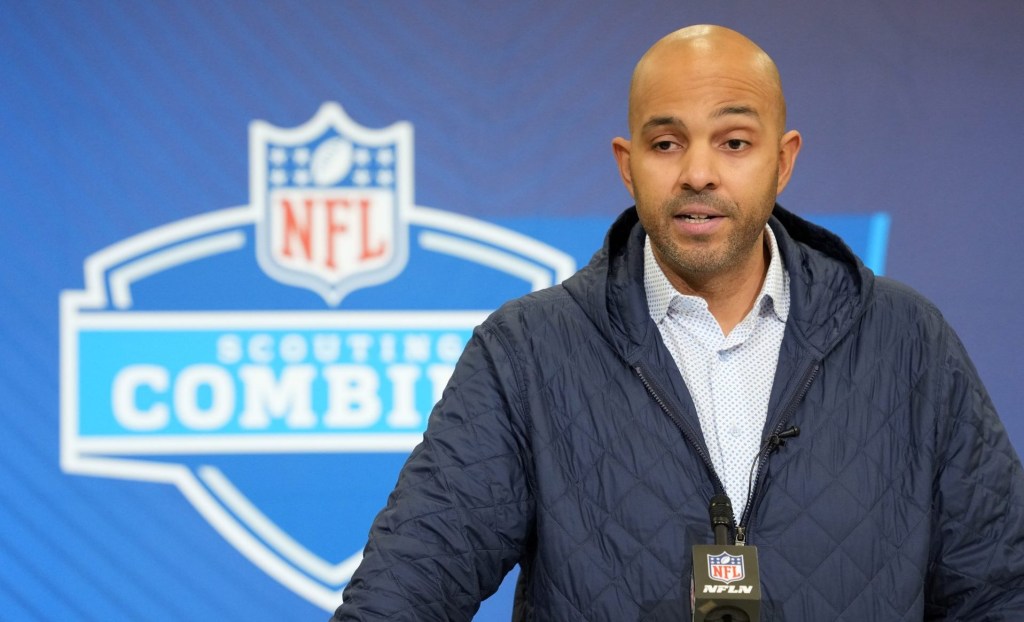

Still, the sport hasn’t broken through. Liz Benn, an MLB executive who was most recently the Mets’ director of major league operations, says that even in conversations with fellow baseball professionals, when she says she pitches on a local rec league baseball team, the assumption is that she misspoke.

“People say, ‘Oh, do you mean softball?’” Benn tells FOS. “Like, no, I mean the sport I said.”

The WPBL founders can point to evidence of growing interest around and awareness of women’s baseball. Players like Kelsie Whitmore and Olivia Pichardo have garnered significant attention for their success on men’s teams. Since 2017, MLB has hosted their own youth programs for girls baseball. And experts think that with the launch of the league, the sport could be at an inflection point—as long as the potential audience isn’t looking elsewhere.

Women’s sports typically face an uphill climb for recognition and viability, but the headwinds seem to be increasingly with them. It’s great news for the launch of new leagues, but the surging interest and investment is also throwing up a unique roadblock for women’s baseball that basketball, soccer, hockey, and others don’t have: competition from a similar bat-and-ball league.

In the wake of recent success of the WNBA, National Women’s Soccer League, and the newer Professional Women’s Hockey League, Athletes Unlimited is launching a new Athletes Unlimited Softball League (AUSL). It will debut as a traveling model in summer 2025, with plans to transition to a city-based format in 2026. (The AUSL joins AU’s existing Championship Season, now renamed the Champions Cup, which is all played at one location.)

AU, which was founded by Jon Patricof and Jonathan Soros in 2020, brought on longtime MLB executive Kim Ng to serve as a senior advisor for the softball league. Ng spent decades working in baseball front offices for the White Sox, Yankees, and Dodgers, most notably for the Marlins as the first female GM in one of the four major men’s pro sports leagues. But before that, Ng played college softball at the University of Chicago.

“I had not been involved in softball for a really long time,” Ng tells FOS. “But this summer, having watched it as closely as I did, and now having the background that I do of 30 years of baseball, I have been quite amazed at how similar the caliber is—the hand-eye coordination, the bat speed.”

One of the biggest issues with the women’s baseball and softball leagues launching almost simultaneously is softball’s thriving place in the sports landscape. It’s not that women can’t and don’t play baseball, but the reality is that softball is considered the place where women participate in bat-and-ball sports. The NCAA does not offer women’s baseball, for instance, and the Olympics feature baseball for men and softball for women.

“We compete with softball, because people’s minds are so locked in that softball is the women’s version of baseball,” says Veronica Alvarez, who is the coordinator of player development in Latin America for the A’s, and also serves as MLB’s girls baseball ambassador and the manager of USA Baseball women’s team.

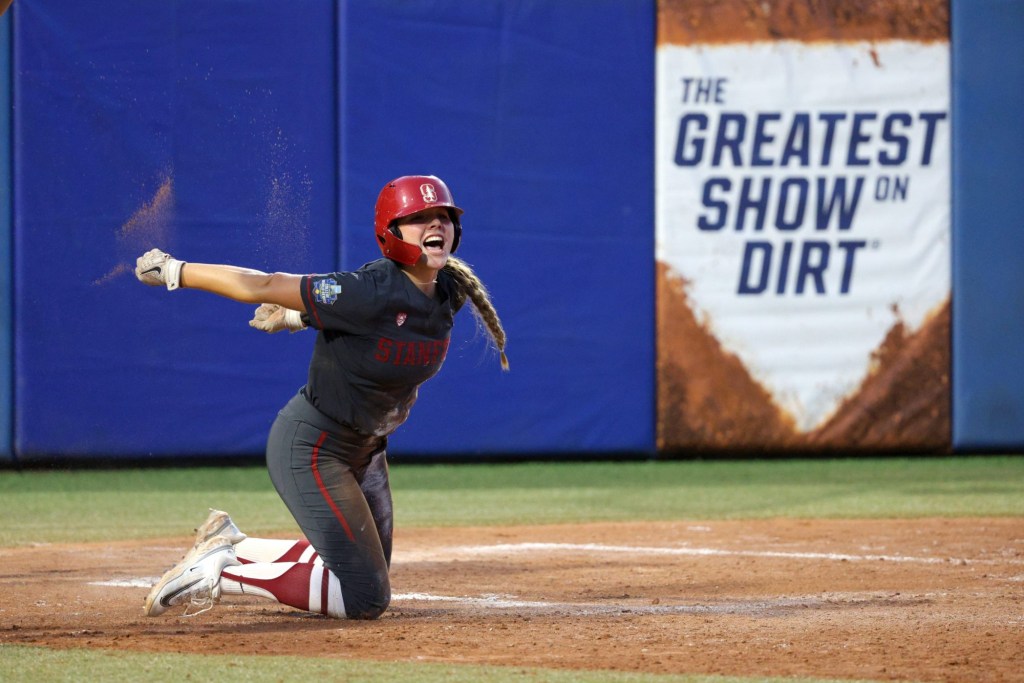

Numbers bear out this story: the Women’s Baseball World Cup finals in Canada last summer, the final game between USA and Japan drew 2,121 fans. Meanwhile the final game of the Women’s College World Series—softball’s pinnacle event outside the Olympics, and one that regularly challenges or bests the Men’s College World Series for eyeballs—drew 12,324 fans in person. Television viewership of that game, which aired on ESPN, peaked at 2.5 million viewers, an all-time high and 24% up from 2023.

This split also has implications for talent. First, there are simply more development opportunities for softball at the youth levels and beyond. A young girl who excels at throwing or hitting a baseball can push to compete with the boys in baseball, or she can—and often does—pivot to softball and find far more opportunities going forward.

Girls and women who are able to find success on men’s teams are met with media attention and cultural kudos, but in softball they can find scholarships and a playing field—literally and in terms of the competition—better suited to their skill set.

In 2022–2023, 21,646 women played college softball while reportedly eight women played college baseball, only one at the Division I level. The same skew exists in high school; in the 2023–2024 school year, 345,451 girls played fast-pitch softball, while only 1,372 girls played baseball.

In the NIL era, there’s even less incentive for a woman to stick to baseball when softball is growing so fast and stealing so much of the spotlight—especially as AUSL launches.

Alvarez was one of those women who played softball in and immediately after college despite always being a baseball player at heart. Now, she’s a champion for girls baseball, but even she admits “the softball talent level is better because there’s more.”

Siegal says many of those elite softball players would likely relish the opportunity to play baseball at a professional level. “Certainly there are many women who play softball who would prefer to play baseball, or who started in baseball and switched over so that they could get a college scholarship,” she says. “There is a place for both women who have been playing baseball their whole lives, and those who will make the switch from fast pitch.”

She is not concerned about filling out WPBL rosters with high-level baseball players in the years to come; she cites the 700 women in the USA women’s baseball database who expressed interest in trying out, and a plan to issue international visas to bring in women from around the world. (Japan has the No. 1 ranked women’s team.)

Alvarez says the most recent tryout for the national team was the best display of women’s baseball talent she’s ever seen. She’s hopeful the WPBL can inspire even more youth and amateur development and push the sport of women’s baseball to match the talent level in softball. It’ll have to in order to succeed. “I do genuinely worry that a good product is going to be essential to the survival of this league.”

Sarah Padove, who oversees baseball and softball development for MLB, says, “I don’t think it’s a secret, softball is certainly massive. But the girls baseball side is growing, and we’ve seen it.”

For now, the WPBL and the game overall still have a lot to navigate with the launch of pro softball and a nascent talent pipeline. But, says Benn, “In women’s baseball, I think the biggest obstacle right now is people just don’t know that it exists.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)