On April 11, 1955, Sports Illustrated published a cover featuring the biggest baseball star in the world. Little did they know how provocative its photo would be.

On the left was Willie Mays, the young, genial and beloved New York Giants center fielder. He was 23 years old, and well on his way to becoming—quite arguably—the greatest baseball player of all time. At right was the team’s beloved manager Leo Durocher, and in the center famed actress Laraine Day, known as “The First Lady of Baseball” because of her then-marriage to the Giants skipper. Day posed between Durocher and Mays, her hands on both men’s shoulders.

It’s an unremarkable tableau to the modern sports fan, but the photo was published just four months before the Mississippi teenager Emmett Till was murdered over a fabricated flirtation with a white woman at a grocery store. SI’s inbox was flooded with letters from fans furious with a Black man getting far too comfortable.

One reader from Fort Worth, Tex., asked the magazine to cancel their subscription as it was “an insult to every decent white woman everywhere.” Another from Shreveport, La., claimed “SI is part of the giant plan to flaunt all decency, so long as the conquered of 1865 can be reminded of their eternal defeat.”

Racially liberal readers, like one boy from Long Beach, N.Y., thought it was “his duty” to condemn the racist outrage. “I was disgusted at the letters concerning the cover of Willie Mays and Mrs. Leo Durocher. I may be only 15 years old but I have more common sense than any adult with those ideas.”

One person claimed to have missed the entire thing: Willie Mays. As Mays became an avatar of the evils of integration or the power of racial progress, he claimed he wasn’t even aware of the 1950s version of a flame war playing out in the comments section.

“And what did Mays think?” wrote biographer James Hirsch, who interviewed Mays extensively for his tome, The Life, The Legend. “He thought the cover was cool and knew nothing of the controversy.”

Whether his ignorance of the furor was genuine or a put-on, it fits who Mays was.

Ever heard the term “race man?” It’s an antiquated 20th-century phrase describing a prominent Black person—almost always a man—who used their platform to advocate for the needs of Black people.

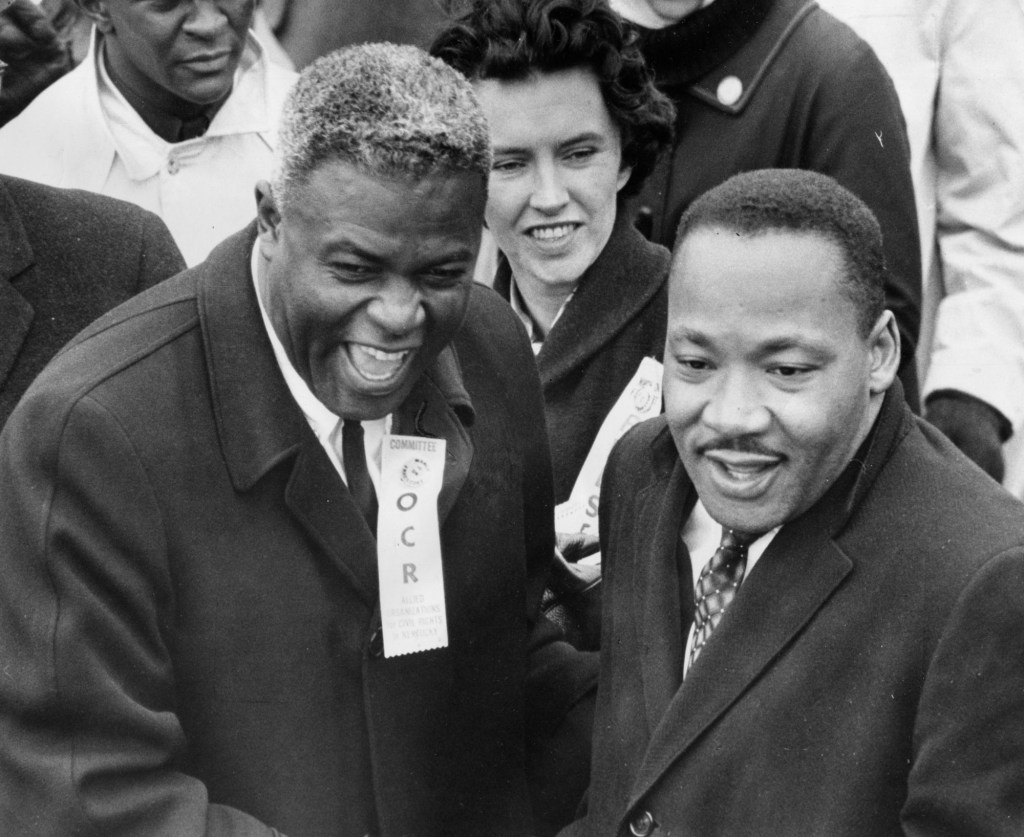

Jackie Robinson was a race man. Jackie Robinson was the race man. Armed with his brilliance and celebrity, he established a Black-owned bank in Harlem that offered fair rates to Black borrowers; fundraised alongside Martin Luther King; urged John F. Kennedy to protect young protestors brutalized by police; and wrote newspaper columns on politics and civil rights. All this after not only breaking American baseball’s color barrier, but becoming one of the best infielders in baseball history.

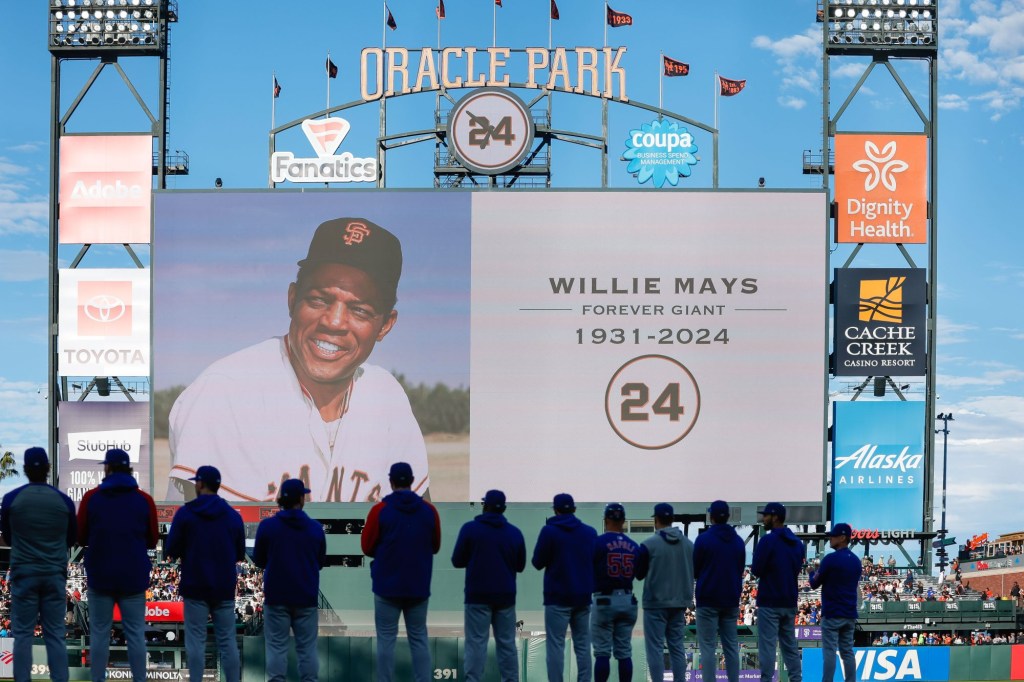

Compare Robinson to Mays, who died in mid-June at the age of 93.

Fans and critics alike found Mays affable and agreeable, avoidant of anything provocative regarding his white peers, even when he found himself standing on explicitly racist fault lines, like when his would-be neighbors harassed and abused him for trying to buy a home. (Mays was moving to San Francisco after the Giants had relocated from Harlem’s Polo Grounds.)

Mays’s then-wife, Marghuerite, condemned the racist “camouflage” of liberal housing discrimination and San Franciscans who “grin in your face but deceive you.” But Mays remained Mays: steadfastly conciliatory. “I’d sure like to live in San Francisco,” he said of the incident. “But I didn’t want to make an issue of it. I’ve never been through this kind of stuff before, and I’m not even mad about it now.”

By the standard that Robinson exemplified, the late Willie Mays was not a Race Man. From Jesse Owens to Maury Wills, Robinson skewered his contemporaries who he believed failed to leverage their platform for the sake of Black people. When Mays declined to participate in Robinson’s 1964 oral history of baseball’s integration, Baseball Has Done It, Robinson let baseball’s biggest star know exactly how he felt.

“There’s no escape, not even for Willie … from being a Negro,” jabbed Robinson. Suggesting Mays had abandoned his Blackness, Robinson wrote that he wished the star would ”think about the Negro inside Willie Mays’s uniform, and tell us one day.” He said, “He continues to ignore the most important issue of our time … and probably keeps looking only to his own security as a great star. It’s just a damn shame he’s never taken part.”

In essence, Robinson was furious that Mays insisted on sticking to sports.

If anyone had earned the right to criticize Mays so harshly—to tiptoe along the edge of calling him an Uncle Tom without using those words—it was Robinson. The battles against segregation weren’t won by turning the other cheek; they were won by men like Robinson, whose fury against racists and mushy-mouthed liberals burned for years.

And yet, Mays wasn’t a proto-O.J. Simpson, allergic to solidarity and pathologically committed to his own advancement. Mays’s doctrine was rarely accounted for in op-eds or speeches, but found in reverence of his peers, many of whom insist he showed up for Black people when it mattered.

“He wasn’t the type of person who’d go out and march or shout, said Dodgers speedster Maury Wills in baseball scribe John Shea’s co-written biography, 24. “But he was right in the middle of it when he needed to be.”

In the 2022 HBO documentary, Say Hey, Willie Mays!, Yankees legend Reggie Jackson directly refuted the notion that Mays betrayed the cause. Listing a consortium of Black superstars—Joe Morgan, Frank Robinson, Henry Aaron, and the aforementioned Wills—Jackson claimed they “to a man said ‘it’s wrong to say that Willie didn’t do enough. Because he was there for me.’”

One day after Mays died, and from Birmingham, Ala.’s historic Rickwood Field, where Mays put on his first major league uniform with the Negro League’s Black Barons, Jackson shared the traumas unearthed by revisiting his hero’s baseball origins, which intertwined with his own.

In vivid detail, Jackson recalled his encounters with white people in Birmingham: They called him the n-word and banned him from hotels. Mr. October, however, swore he wouldn’t have let it slide no matter the cost. “I’d have beat somebody’s ass, and you’d have saw me in an oak tree somewhere,” he told the Fox pregame crew.

Some work in quiet. Others go on national television ready to square up with Bull Connor’s ghost. Jackson and Mays had different approaches to racism, clearly. But their differences only magnify the love and respect Jackson had for his forefather.

Like Mays, some fans, media, and players saw Aaron as an affable gentleman who simply ignored the racism he experienced. It’s not true, but it’s a criticism Aaron was well aware of.

“You can’t be everybody, and you can’t do every thing. Sometimes I kick myself in the rear end for not being as good as Dr. King was,” Aaron wrote.

Hammerin’ Hank, GOATed and sainted, a man who persevered through piles of death threats mailed to his home for the cardinal sin of being better than a white man at swatting dingers, sometimes regretted being less rhetorically potent as, literally, Martin Luther King. “You do the very best that you can,” Aaron wrote. “I’m sure Willie did about as well as he probably could do.”

Like Aaron, Mays understood that Robinson, like Martin (Luther King), was built differently. And not everyone is made for the road his forerunner traveled. Few have the innate character or accountability needed to live like Robinson or the athletes who have made activism an explicit part of their public lives. Perhaps Mays knew that whether out of ineloquence, ignorance, or arrogance, many athletes would tie themselves into clumsy rhetorical knots trying to be something they’re not.

In the decades since Mays and Aaron were in the crucible of mid-century American baseball, the blatant violence and racism they faced has decreased—somewhat, and only intermittently. But the pressure “to be everybody, and do every thing,” as Aaron wrote, has become a defining trait of American sports and culture at large.

What do the GM of the Houston Rockets and the best basketball player in the league think about autonomy for Hong Kong? What does intersectional feminism mean to Caitlin Clark? What does Taylor Swift think the Democrats should do in this election? I need answers; can someone get Ja Rule on the phone?

This is not to say that athletes and celebrities are incapable of sincere activism, or above critique when they abandon their power and influence for the good of others, but that the complex and nuanced ways Aaron and Mays chose to handle the pressure to be an activist are largely unfamiliar today. They did not dismiss the weight of their celebrity with a churlish rejection of any responsibility, nor were they comfortable leading or pontificating on every single issue.

That’s dignity. Not everyone needs to be more than an athlete at all times.

His peers found his quiet leadership essential. His fans—conveniently, sometimes—believed his meekness and joy on the field meant he didn’t worry about his place in the world. But Mays’s comportment was the product of careful consideration, he wrote in his 1966 autobiography.

In Willie Mays: My Life In and Out of Baseball, Mays came closer to a manifesto than he ever had, a vision in which not just Black athletes, but Black people, weren’t relentlessly politicized for their very existence.

Mays wrote that for him, “The sun doesn’t rise or set whether I hit a home run or not. For me, it rises and sets on a little guy whose name is Michael Mays: my son. He will know his father not as the first Negro player in the majors, because I wasn’t but as maybe—all things considered—the first one you could point to and say ‘Look what he did; instead of, ‘Look, he’s Negro.’”

“All the Negro players who came up to the majors before I did … had the same scouting report. First they said the player was Negro, and then they said he was great. With me they said great, then they said Negro.”

This isn’t political, not in the way we usually mean it. Mays doesn’t condemn racist laws or police. But it works in tandem with Robinson’s approach, envisioning a world where bigotry isn’t just a burden to bear but also a mandate to fight against.

Some people want to be more than an athlete. Mays fought for your right to be simply an athlete. Or better yet, to just be. I don’t know if Mays’s assessment was as true as he believed, then or now. But I can respect it.

“No question about what Jackie Robinson started,” Mays said, in deference to his hero, and mine. “But maybe I started something, too.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)