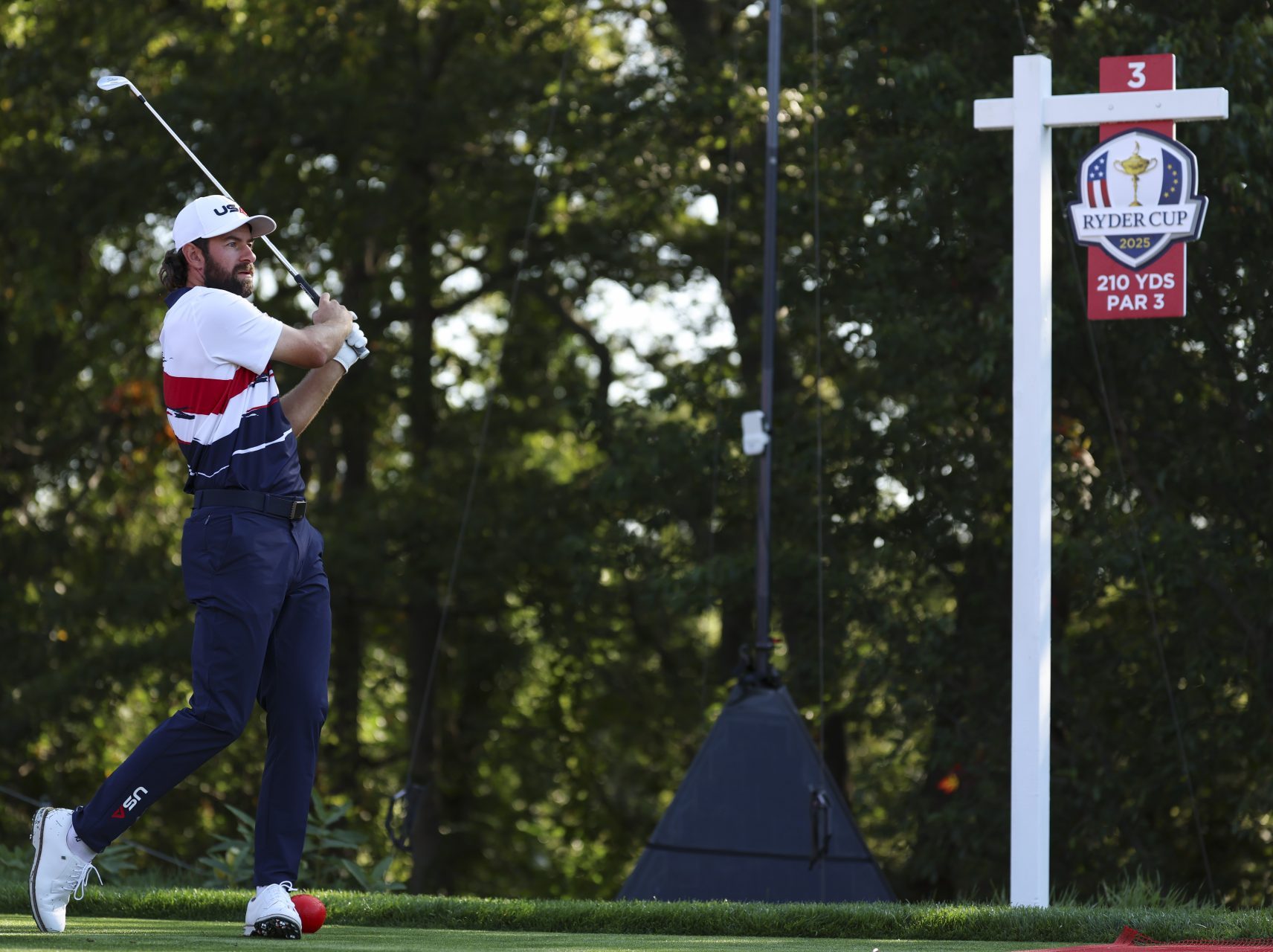

When the 45th Ryder Cup tees off Friday morning at Bethpage Black Golf Course just outside New York City, a new era will begin for the storied team competition: pay for play. Sort of.

Just over 98 years after captain Walter Hagen led the U.S. to a 9.5–2.5 victory over Great Britain in the first Ryder Cup, this week’s 12 U.S. team members and captain Keegan Bradley will become the first individuals in the event’s history to receive monetary compensation for competing.

The PGA of America, which runs the Ryder Cup’s U.S. operations, is paying each player a $200,000 stipend, in addition to a $300,000 allocation to be directed to a charity or charities of each player’s choice. That’s $6.5 million in total ($3.9 million specifically for charity and $2.6 million with no caveats), up from $2.6 million in all previous editions since 1999 via $200,000 per-player allocations for charity.

While the PGA of America said no players asked to be compensated, the concept of being paid to play for one’s country in a national, team-based competition is controversial and has led to plenty of negative feedback since the move was announced in December—especially from their rivals across the pond, who are not paid by Ryder Cup Europe, the entity that runs the event’s European operations.

“I personally would pay for the privilege to play on the Ryder Cup,” Rory McIlroy told the BBC last year. “The two purest forms of competition in our game right now are the Ryder Cup and the Olympics, and it’s partly because of that, the purity of no money being involved.”

“We don’t need to be playing for money,” European team captain Luke Donald said in an interview with Skratch, while former European player Colin Montgomerie told Sports Boom it “leaves a sour taste.”

Even former U.S. team member Patrick Reed said earlier this month that compensation is “unnecessary.”

The tenuous situation dates back to 1999, when Tiger Woods and David Duval led an effort to shift the economics of Ryder Cup participation, which ultimately led to the PGA of America allocating a charitable $200,000 per player.

“We didn’t want to get paid, we wanted to give more money to charity, and the media turned it around against us and said we want to get paid,” Woods said last December when the new stipend structure was announced. “No, the Ryder Cup itself makes so much money, why can’t we allocate it to various charities? And what’s wrong with each player, 12 players getting a million dollars and the ability to divvy out to amazing charities that they’re involved in that they can help out?”

Woods is right that the Ryder Cup is by far the PGA of America’s most lucrative event, and “financially critical” for the organization, chief commercial officer Jeff Price told Front Office Sports. “I mean, we operate on a break-even basis, as a 501(c)(6), every four years,” Price said.

In the 2021–22 fiscal year, which included the last home Ryder Cup for the U.S., the PGA of America reported record revenue of $192.13 million, and a profit of $73.72 million. The following two years it reported losses of $18.28 million and $12.64 million. Figures from the 2024–25 fiscal year will be released in 2026.

While player pay is a Ryder Cup first, other team golf competitions have already compensated participants.

The PGA Tour–organized Presidents Cup, a U.S. vs. international (excluding Europe) event, has paid all players, captains, and assistant captains a $250,000 stipend since its 2022 event.

The Solheim Cup, the women’s equivalent of the Ryder Cup, has not publicly revealed whether it compensates players, but a spokesperson for the LPGA, which helps run the event, told FOS: “Solheim Cup players, captains, and caddies receive a modest stipend to help offset expenses, but they do not receive prize money or specific charitable donations. All event-related travel and accommodations are fully covered.” The stipend is in the five-figure range, the spokesperson said—so at least $10,000.

The 2023 Ryder Cup in Rome produced the most controversial moment in the compensation debate: Patrick Cantlay’s “HatGate.” During the event, Sky Sports’s Jamie Weir alleged “Cantlay believes players should be paid to participate in the Ryder Cup, and is demonstrating his frustration at not being paid by refusing to wear a team cap.” European fans latched on to the rumor, waving their hats to taunt Cantlay. But when asked whether players should be paid, Cantlay said, “It’s not about that,” and that the hats were too small.

Many U.S. players on this year’s team have indicated their $200,000 will be donated to charity, including Cantlay. His agent told FOS he will be donating his $200,000 stipend (as well as his $300,000 allocation) to charitable causes with an emphasis on educational development for children of military veterans and first responders including the First Responders Children’s Foundation and Folds of Honor. But don’t expect to find out what every player is doing with the cash. “I think for everyone it’s a personal decision,” Bradley said Monday. “A lot of guys aren’t comfortable sharing what they’re going to do with their money.”

Earlier this year, PGA of America CEO Derek Sprague told FOS he was content with the stipend structure. “Would I like them to play for just the flag, so to speak? Absolutely,” Sprague said. “But, at the end of the day, they are giving up a week. They are coming and playing this great event.”

Last week, Price told FOS he also supported the new payments. “From my perspective, as the commercial lead, more dollars are going to charity,” he said. “The players have the discretion to do what they’re going to do.”

The U.S. Ryder Cup team’s new monetary era will no doubt be a major storyline this week—as well as at future editions—and there’s likely no going back for the players. As Price said, “They are the Ryder Cup.”