Last week, Wizards and Capitals owner Ted Leonsis gave his seemingly definitive answer to a question that is being asked in sports markets throughout the country and once, by The Clash:

“Should I stay or should I go?”

Leonsis was trying to move the two teams out of the nation’s capital and across the Potomac River to Alexandria, Va. The teams have been in D.C. for 26 years, and the threatened move was met with an uproar on both sides of the river, with loyal D.C. fans aggravated by the potential loss of the teams and Virginians uninterested in subsidizing Leonsis, who is worth billions.

After months in which a handshake agreement with Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin never went beyond that, Leonsis pivoted and re-upped with the city of Washington for a 25-year lease plus $515 million in renovations to Capital One Arena, where both teams play.

“I think this was a risky deal,” Leonsis tells Front Office Sports Today. “We had reached [an] agreement on a framework of a development, and I hadn’t signed anything. I want to reiterate that it’s highly unusual that you don’t sign anything; you have a handshake.”

Leonsis is one of several U.S. sports owners who has recently threatened to move his team without public funding for an arena or stadium. Several well-established franchises are discussing moves, with the plans ranging from embryonic to nearly complete.

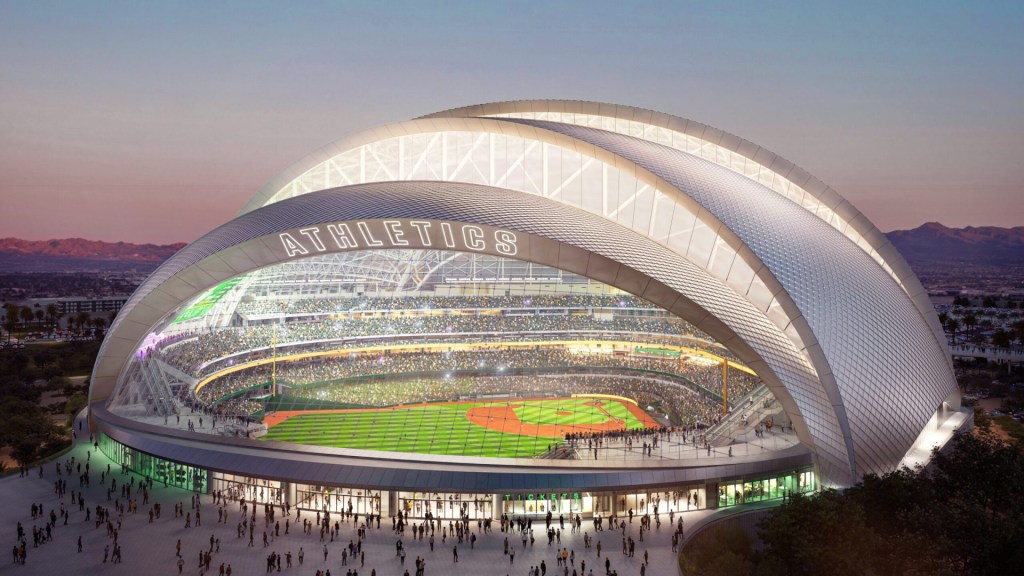

On Tuesday, Kansas City, Mo., residents will vote on a sales tax to help pay for renovations to both the Chiefs and Royals stadiums, with no clear indication which way it will go. Both ownership groups have said they could eventually leave town if the tax doesn’t pass. The A’s are trying to leave Oakland with an exit plan that is still held together with bubble gum and paper clips despite MLB owners giving them the green light to relocate. The Bears flirted with the suburbs but said they plan to stay in Chicago, while the White Sox are currently teasing a possible departure after the Rays and Brewers successfully secured public funding.

“This is going to happen again and again,” says Victor Matheson, a sports economist at Holy Cross. “And what’s happening is that whole stadium wave that started in 1992 with Camden yards, all those stadiums that were built in the ’90s and early 2000s and all have 30-year leases, … as soon as the 30-year leases expires, now the teams can make these credible threats.”

Matheson said he thinks sports owners have become overconfident in their plans after seeing the Bills get $850 million from the state of New York for a new Buffalo stadium, and Oklahoma City residents overwhelmingly voted yes for a new $900 million arena for the Thunder.

“I think a bunch of teams have kind of come at this and said, ‘Oh, this is going to be easy.’ And they kind of gift-tie it so they don’t bring their A game,” Matheson said. “There’s no way that Monumental Sports was bringing their A game. They made unforced error after unforced error just assuming they could have a walk in the park.”

Leonsis praised Washington, D.C., mayor Muriel Bowser in his conversation with FOS, and called her “the hero in all of this.” As long as the deal with Virginia and Youngkin was nonbinding, Bowser could work on an offer, and Leonsis could shop around with other states. Leonsis cited the extra square footage from a bankrupt Washington mall as a critical part of the D.C. deal for him.

Andrew Zimbalist, a sports economist at Smith College who has worked with cities, teams, and leagues on stadium deals said both economists and media “are onto the game” owners play with the supposed economic impact of their projects. One of the Virginia’s Senate’s biggest issues with Leonsis’s plan was they didn’t want to subsidize a billionaire, and that argument has grown louder in recent years across the country.

“When you put forward your [tax increment financing] district and you outline your intentions for who is going to go where, which retail, which hotel, which commercial building, all that stuff, all that is at the beginning is really a wish list,” Zimbalist says. “You might have some hotel company saying, ‘We’d be interested in exploring that,’ and you might have a concert hall operator saying, ‘Yeah, we’d be interested in exploring that,’ but it’s not committed.”

It’s why, Matheson says, other owners should look at Leonsis’s situation and realize they shouldn’t be as public with their plans if they want to succeed. In many ways, it’s a numbers game. The fewer people owners have to win over, the better.

“If you want to be successful, do as much behind the scenes as you can,” Matheson said. “If things go to vote, you can’t be sure one way or the other if you’re going to win, but you have a whole lot better chance at winning if you do this all in the smoke-filled back rooms without anyone else around. The majority of the city council is going to be able to fit in the owner’s box. You’re not going to be able to fit the entire voting population in the owner’s box.”

The Chiefs and Royals could win Tuesday’s vote, but at least there’s a vote.

“The taxpayer is the underdog in every single game going forward because again with the leases expiring basically that hands every sports team basically a 14-point head start in every game,” Matheson says.

“So the taxpayers are huge underdogs everywhere, but as long as these things go to votes, taxpayers probably have fighting chances.”

Editors’ note, Apr. 2 at 9:10 a.m. ET: An earlier version of this story misstated how long the teams have played in Washington, D.C. The teams have been there for 26 years, not 51.