On a soupy, August Saturday in Brooklyn, N.Y., more than 10,000 fans at the Barclays Center started the evening like any other. They streamed into the arena through windy security lines, scanning QR codes and checking bags, then moving on to buying hot dogs, kettle corn, and merch.

But the typical smell of the home court of the Brooklyn Nets and New York Liberty—hardwood and tile floors buffed with cleaning chemicals—had been replaced with an aroma of dirt, leather, and cow manure.

For the first time in the arena’s 12-year history, the floor of Brooklyn’s premier entertainment center was covered in more than 750 tons of soil for the debut of Professional Bull Riders (PBR). Hundreds of feet of fencing was installed overnight to ferry more than 50 bulls from across the country into the bowels of the stadium, where they awaited their eight-second spot in the limelight.

“Traffic was just freaking horrible all the way up there,” says Mike Miller, one of the stock contractors who breeds PBR’s bucking bulls, which can weigh up to 2,000 pounds each. “You’re driving a trailer full of bulls on these tiny little two-lane highways.”

The Texas-based PBR—essentially the NFL of rodeo—has hosted an annual event at Madison Square Garden since 2007. But this was the promotion’s first time putting on a rodeo in Kings County. It’s part of a larger push to thrust the sport into the mainstream, capitalizing on the surging popularity of the cowboy aesthetic in America’s cultural zeitgeist. From indisputable hit Paramount+ TV series Yellowstone and its seemingly endless torrent of spin-offs, to Beyoncé’s platinum record Cowboy Carter and Pharrell’s Wild West–inspired Louis Vuitton collection at Paris Fashion Week in January, the cowboy gold rush is on.

And PBR is looking to strike it rich.

“I think it really started with the Yellowstone phenomenon, and the millions of people that were tuning in and getting a slice of [Western culture] in TV parlance,” PBR CEO Sean Gleason tells Front Office Sports. “The cowboy hat isn’t turning people off now. It’s grabbing their attention.”

The most cowboy activity of all, rodeo, is already riding the wave. According to data provided by PBR, the sports property has experienced a 23% increase in ticket sales between 2022 and 2023, on top of selling out 38 separate events. More than one million people attended PBR events in 2023. Its audience is also spiking on social media: Both PBR’s TikTok and Instagram accounts boast more than 2.5 million followers—numbers that represent huge growth for the league and spur massive fan engagement.

PBR has been valuable for a long time: The organization was acquired by publicly traded U.S. sports, entertainment, and talent management company Endeavor Group Holdings in 2015 for $100 million. Since then, its footprint has expanded. In May, it struck two new media-rights agreements. The league has partnered with CBS Sports and Dr. Phil’s Merit Street Media for expanded distribution and more consistent, desirable broadcast windows, plus shoulder coverage including pre- and post-event shows and news. It’ll be the most live TV airtime the sport has ever seen, building on an existing audience of 31 million viewers on CBS in 2023 alone. The new deals will also increase coverage of women’s rodeo. On the sponsorship side, PBR has partnerships with brands including Wrangler, the U.S. Air Force Reserve, Monster Energy, Yeti, and Cooper Tire, along with several alcohol companies including AB InBev and BeatBox Beverages.

There’s more for rodeo, believe its proponents. With its growth throughout the past decade, PBR’s value is likely much higher—and the rodeo market is ripe for explosive growth.

Rodeos have always been money-making entities, both for PBR and its host cities. Officials from Cheyenne Frontier Days, the largest rodeo in the U.S., reported that its 2023 event generated more than $40 million for its local economy in Wyoming through tourism and tax revenue. The Calgary Stampede and the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo also generate hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

Now, however, PBR is attempting to take the sport out of the American West and into nontraditional markets, adding shows in—and seeking revenue from—definitively non-cowboy cities, including Pittsburgh, Albany, Brooklyn, and Fort Lauderdale, throughout the past year.

On its face, professional bull riding is simple: A rider is expected to maintain their position on top of the bull for eight seconds. If the rider can complete the herculean task, they are given a score for their ride out of 100: 50 points for the cowboy, and 50 points for the bull itself, which is considered to be more akin to a teammate than adversary. Each bucking bull’s stats are tracked in PBR standings, and a bovine champion is crowned at the end of each year. And, of course, they’re all named: Recent notables include Squealin’ Kitty, Man Hater, Flapjack, and the unassuming Richard.

“They’re our dancing partner, our way of survival,” says Ezekiel Mitchell, a PBR rider from the tiny Texas town of Rockdale, who has become one of the sport’s biggest stars. “[Rodeo is] the thing that actually feeds a lot of people that I know. We have so much more respect for the animal than people give us credit for.”

But that doesn’t make getting on a bucking one-ton animal any easier. “Take your truck and go drive it off a cliff and then try to control it on your way down, without hitting any trees,” Mitchell says. “That’s pretty much what it is.”

Mitchell has seized the surge in Western-culture interest for himself, parlaying his PBR fame into appearances in music videos for country hip-hop artist Breland as well as a merchandise collab between Arby’s and rapper Pusha T. “Up until the emergence of Yellowstone and Beyoncé’s album and stuff, a lot of people thought we’re just dumb country folk that don’t know much,” he tells FOS.

In the drive for mainstream appeal, the PBR promotion has also experimented with the sport’s format, adding a nationwide series of “team events,” in which two teams of five bull riders compete against each other by tallying their individual scores together. These team events are designed to make the sport easier to understand for a growing base of new and casual fans, particularly in nontraditional locales like New York, says PBR CEO Gleason.

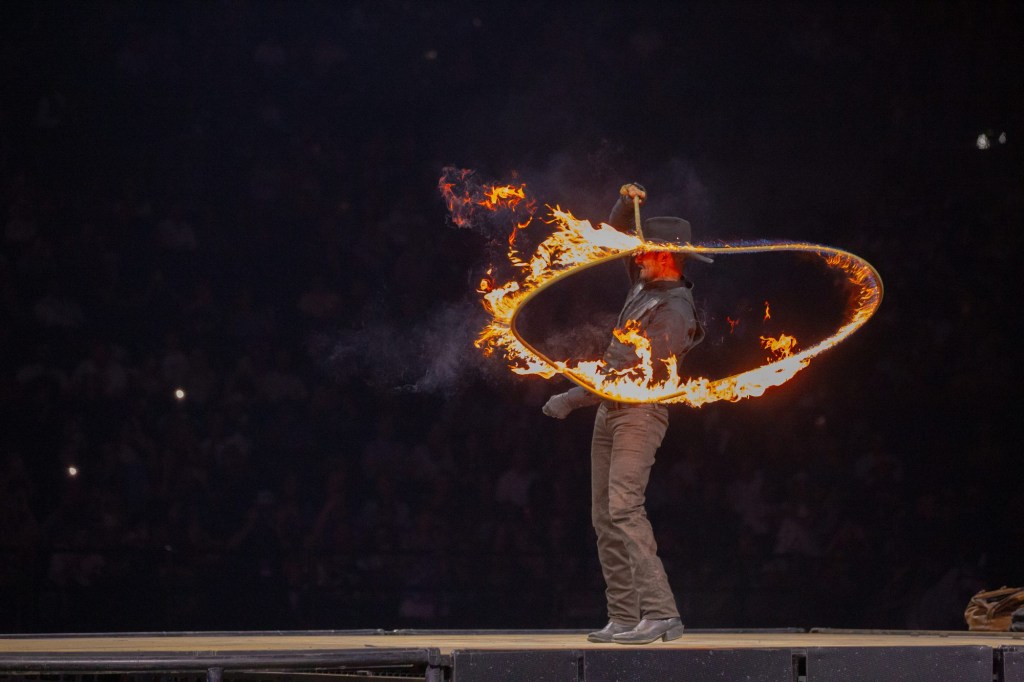

This slate of 10 teams includes the New York Mavericks, who competed for the first time in front of their home fans Aug. 9–10 at Barclays. The PBR product can only be described as a cacophony of sound and fury. Each night opened with fireworks, a “face-off” between each opposing team, and America’s Got Talent competitor Loop Rawlins ringing in the competition with a crack of his (literally) flaming whip.

The New York Mavericks won both of their inaugural home competitions, called Maverick Days, pulling off an upset win against the Kansas City Outlaws, and a rout of the Florida Freedom on night two. “This is what it’s all about,” says Kody Lostroh, head coach of the New York Mavericks and 2009 PBR World Champion. “We are damn sure not the norm for people to see here. Everybody in New York is always passionate about their sports and their teams, so to be part of that now, even if it’s not where we’re typically used to riding, is awesome.”

Cooper Davis, 2016 PBR Champion and one of the sport’s most public-facing personalities, says he has seen the surge in demand for everything cowboy in recent years. He agrees the Western culture appetite has helped drive PBR to new heights.

“Everybody that attends now isn’t a cowboy, and I love that,” says Davis, who is from Jasper, Texas, a little town near the Louisiana border. “That’s kind of how I grew up. I didn’t have a background in rodeo. My family didn’t have a background in rodeo. But I loved watching it on TV. So it’s cool to see outside influences get involved in bull riding.”

In Brooklyn, established PBR fans mingled with brand-new, curiosity-driven spectators. Annie Davis, a 26-year-old Manhattan resident, had never attended a rodeo before night one of PBR’s Team Series. “It’s very thrilling,” she tells FOS. “You don’t have to know anything about any of the bull riders to understand; you don’t have to understand stats to see if they can sit on a bull or not. We were screaming the whole time.”

“When you see a perfect ride, a rider and a bull, it’s like poetry in motion,” says Evelyn Robinson, who classifies herself as a PBR superfan. A Brooklyn native, Robinson now lives in California and attends five or six events a year. The growing television presence of the sport had her “immediately hooked,” she says: “I thought, who does this, consciously gets on an animal this size? It’s unpredictable.”

The rodeos have become a kind of fashion show, too. Fans had cobbled together pseudo-country outfits for the occasion: Flannels, skinny jeans, gas station cowboy hats, and Chelsea boots. (Gothamist noted New York City has been flooded with cowboy boots: “I’ve always liked red and I’ve wanted a statement shoe,” noted one fashion-forward interviewee on the streets of Brooklyn.) Like Jordans and basketball, the Western aesthetic is central to the sport of bull riding, and represents its own massive industry, which is projected to soar to more than $136 billion by 2031.

“Our business doubled in three years,” says Beth Cross, CEO of Ariat, one of the largest Western-wear companies in the world. “The Western lifestyle, and especially associated with country music and some of the sports … it’s a big, small niche.”

Rodeo’s path to more growth may seem to be paved with riches, but it’s not without its own precarity.

The sport has been targeted by protestors who accuse PBR and rodeo writ large of animal abuse, because of the sport’s use of flank straps and spurs to distress the bulls into bucking off their rider. PBR has argued injuries to bulls are exceptionally rare, claiming that a bull will suffer a career-ending injury only once every 5,000 rides, and a mild injury once every 400. It claims only two bulls have been euthanized since 2006. This data could not be independently verified by FOS.

These controversies have gained enough traction in some new, untraditional markets to threaten PBR’s ability to host events. Some cities, including Fort Wayne, Ind., as well as Pasadena, Calif., have already banned rodeo sports, and a bill to ban rodeo from L.A. city limits was introduced in 2021, shortly after an event at Crypto.com Arena. That bill is currently working its way through committee, and it could come to a vote as early as this year.

Gleason tells FOS he believes the animal rights activists and legislators championing the bill are “terrorists,” and he claims that the attempt to ban rodeo sports from L.A. is a rejection of American cultural heritage. “I honestly believe most of those people just detest cowboys,” Gleason says. “It’s the antithesis of how they view themselves and their loafer-wearing, don’t-get-dirt-on-me, citified way.”

For now, however, PBR has the wind at its back. Pittsburgh, another city that had outlawed rodeo back in 1992, recently inserted a provision to repeal any ban on rodeo sports into the Pennsylvania budget this year. That bill passed with overwhelming bipartisan support, and it was signed into law by Democratic Governor Josh Shapiro. Shortly after, PBR announced it would host its first event in the city in January 2025.

Gleason says no matter legislation or pushback, the sport is here to stay, even if Western culture’s moment fades. “We were here before the trend, we’re here during the trend, and we’re going to be here after the trend.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)