Madison Chock took the Olympic ice in Milan for the free dance with a red matador cape trailing her, the fabric doubling as a skirt. It’s the third version of a costume that has evolved across the American ice dancer’s entire competitive season.

The first iteration, with gold crystals and glittering floral lace, required roughly 135 hours of work in the Montreal atelier of Mathieu Caron: designing, fitting, airbrushing, and placing crystals one by one. Since then, the fabric has been swapped, the color palette tweaked, and the silhouette refined—each revision adding to the price tag of what is already one of the most expensive garments in any Olympic sport.

Olympic figure skating is a global showcase not only of talent and athleticism but also of handmade, one-of-a-kind designs. Each costume is worn for about four minutes of competition and can cost anywhere from $1,500 to $9,000-plus.

They are, for most skaters, an entirely out-of-pocket expense.

“It’s so expensive, and we wear it for a short amount of time, but it’s something really unique about our sport,” says retired Olympic skater Mariah Bell, who competed at the 2022 Beijing Games. She estimates she spent between $2,000 and $6,000 per dress during her career.

Skaters typically need at least two per season, for the short and free programs. And in figure skating, a program-component score evaluates everything beyond the technical elements—including how a skater presents. “Your packaging and what you look like can really play into that score,” she says. “It’s really a whole performance.”

Caron, whose 16-person studio created costumes for 23 Olympic skaters from eight countries this cycle, charges an hourly rate, since every project demands different levels of complexity. He estimates that about 60% to 65% of a costume’s cost is labor; the rest goes to fabric and rhinestones. A single intricate dress—like the hand-painted striped one for 17-year-old Japanese skater Ami Nakai, competing in women’s singles in her first Olympic Games—can take about 90 hours of work.

“It’s not just a dress; it’s a full service,” he tells Front Office Sports. He’ll sometimes travel to meet skaters where they train, and in the weeks before the Games, the studio fields a flurry of last-minute requests. “Can you add the stones? Can we change that part?” he says, describing the fine-tuning. “Everyone wants to make sure that they are at their best.”

Typically, Atlanta-based designer Brad Griffies has a three-month queue for his custom designs. He works solo, sketching, sewing, and placing every crystal by hand. But three weeks before the Games, he got a call from Mexican skater Donovan Carrillo, who needed a costume for his short program. Normally, Griffies would make a client wait—but the Olympic stage changes the calculus.

“When you have the chance to dress someone at the Olympics, you try to move mountains to make that happen,” he tells FOS.

Griffies has been making costumes for close to 30 years and is known in the skating world as the “Bling King.” He designed the now-iconic blue ombré Sleeping Beauty dress for 2014 Olympic team bronze medalist Gracie Gold.

His custom work starts at $1,500, but it can quickly climb. Much of the cost comes down to crystals. Swarovski stones, the gold standard, can eat through hundreds of dollars before a single one is affixed to fabric. But the extra sparkle is worth it. “It’s like buying a Louis Vuitton bag versus something from Marshalls,” he says.

The cost is especially staggering considering figure skating is hardly a lucrative sport. Sponsorships often follow for winners, but Olympic gold medalists receive only $37,500. Chock and partner Evan Bates earned $22,500 for their silver-medal performance. (Chock, however, is already an ambassador for Kim Kardashian’s Skims brand.)

A handful of elite athletes receive partial funding through their national federations, and Bell says U.S. Figure Skating offers stipends that can be allocated toward costumes if an athlete chooses—though only once a skater reaches the World team level. Some international federations cover a portion of costs directly, and Caron says he occasionally receives payments from agents.

Occasionally, the fashion world steps in: Canadian pairs skater Deanna Stellato-Dudek, the 42-year-old 2024 world champion who was just cleared to compete at these Games after a training injury, will take the ice in costumes designed by Oscar de la Renta. The cost is covered by the fashion house.

But that kind of outside support is increasingly rare. Griffies recalls that in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was more common for independent benefactors to sponsor skaters’ costumes and training, which ran into the tens, even hundreds of thousands.

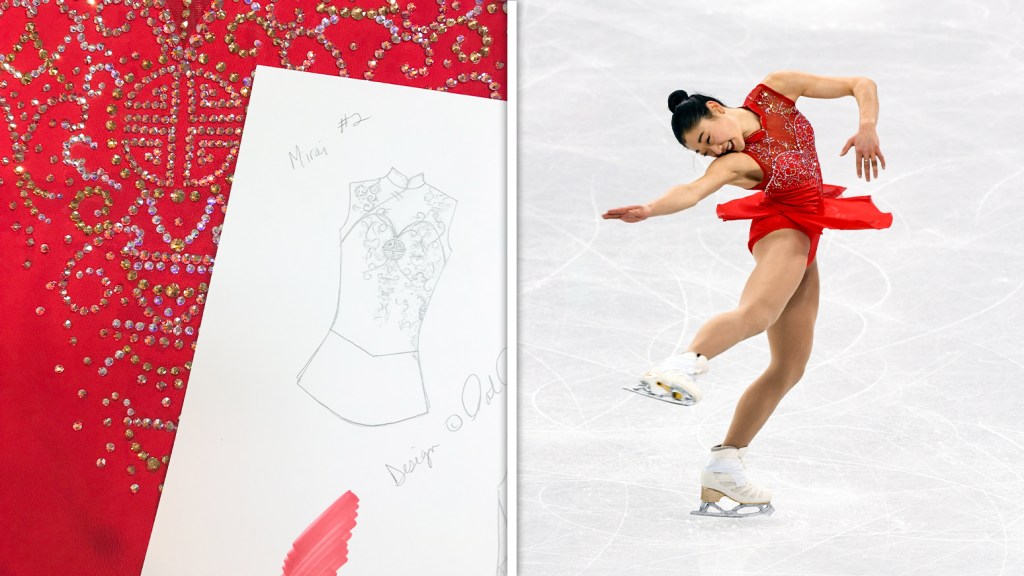

Houston-based designer Pat Pearsall, who has been making costumes for more than 30 years, has at times sponsored an elite athlete, covering the cost of their costumes. For several years, that skater was Mirai Nagasu, the 2018 Olympian who became the first American woman to land a triple axel at the Games. “I’m so appreciative that I had that spot because there was a lot of work that went into those costumes,” says Nagasu.

Before that sponsorship, Nagasu paid full price for custom pieces while competing on the international circuit from the age of 13. “I love the glamour of it all, but on a day-to-day basis, it’s not at all who I am,” she says. “I’m a frugal queen.”

For the Miss Saigon–themed free skate in which Nagasu landed the historic jump, she and Pearsall gave careful thought to the weight of the dress. They designed a full stoning pattern, then deliberately stripped portions of it away so the costume stayed light enough for the jump while still making an impression under arena lights. “I would just take the original, would just randomly erase parts of the design of the dress, and it just came out perfect,” Pearsall recalls.

Pearsall’s prices range from $1,200 to $5,000, and she hasn’t raised her base in years. “I had a daughter that skated, and I’m well aware of the costs associated with this sport,” she says. “I never wanted my work to end up causing more stress for a skater or their family.”

Below the elite level, families get creative. Nagasu recalls borrowing dresses, shopping at consignment “skate swaps,” and watching her mom sew costumes when she was young. Bell wore hand-me-downs from her older sister before graduating to custom pieces.

Caron’s studio has responded to the accessibility gap with Iconic Skate, an online platform that offers preset options for skaters to create semi-custom looks at a lower cost. Pearsall is also developing a basic ready-to-wear line for younger competitors who, she says, “deserve to have something beautiful and something that fits well and that looks great on them, and something that they can afford.”

But on the Olympic stage, where careers are made in four-minute bursts, the calculus remains the same. “You have very little time to make an impression,” Nagasu says. “The costume is a huge part of that.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jun 15, 2025; Seattle, Washington, USA; Botafogo owner John Textor inside the stadium before the match during a group stage match of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at Lumen Field.](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26465842_168416386_lowres-scaled.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)