Just over a mile from Seattle’s Climate Pledge Arena, the longtime home of the SuperSonics, the Museum of History and Industry houses about 5,000 remnants of the former NBA franchise.

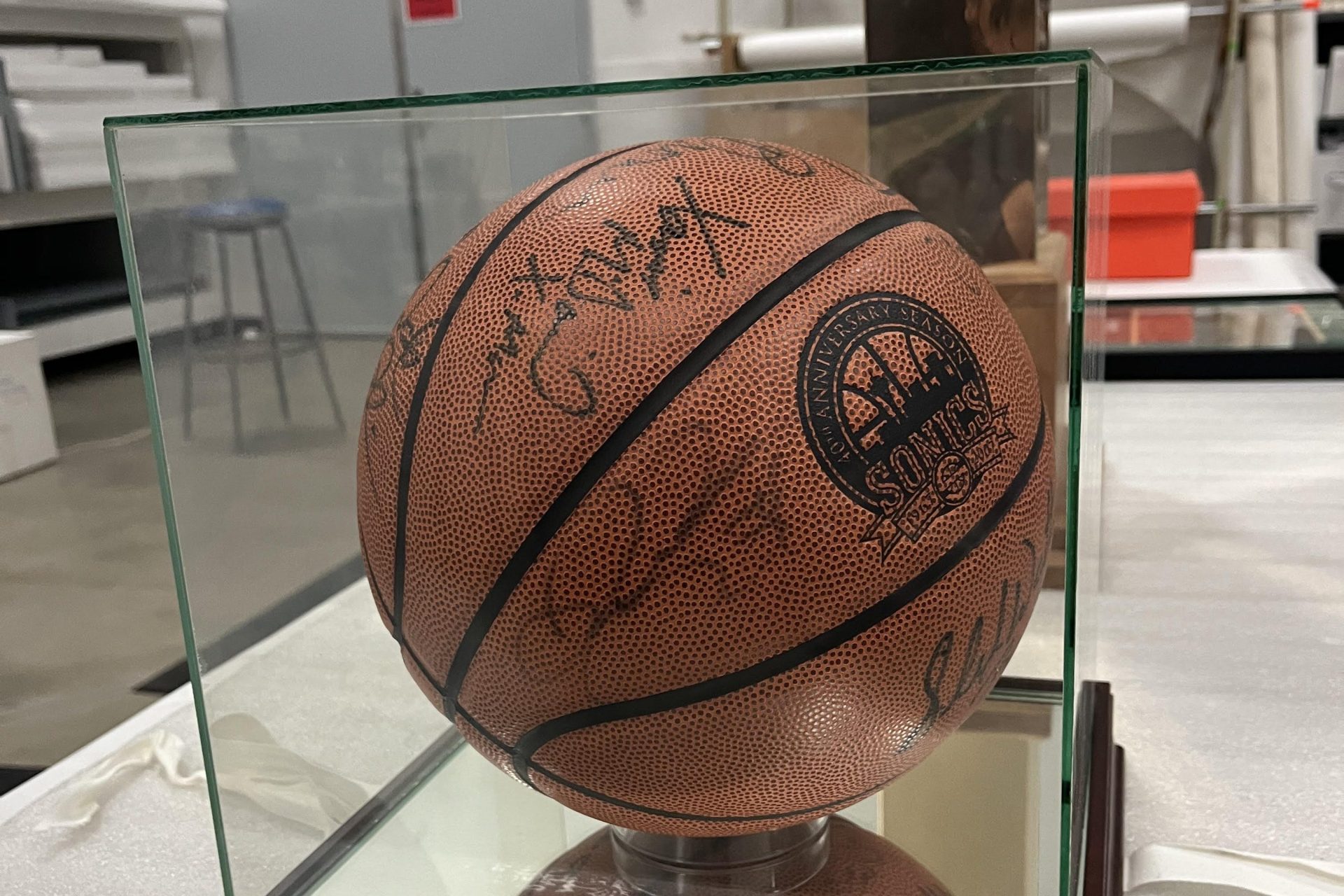

Sitting on 20 warehouse shelves are promotional game material, arena-sized banners, and memorabilia—all collected from the team’s four decades in the Pacific Northwest before owner Clay Bennett failed to secure public funding for a new arena and relocated the team to Oklahoma City.

Only three items are on display: the team’s 1979 Larry O’Brien Trophy, a pair of size 20 practice shoes, and a pennant.

In 2008, Bennett and the city of Seattle reached a $45 million settlement, breaking the team’s lease with the arena and clearing the way for the Sonics to become the Thunder. As part of the agreement, the city kept the Sonics’ championship banners, trophies, retired jerseys, and more. Many items went to OKC in the divorce, like locker-room flat screen TVs, courtside seats, office chairs, CDs, a sound-effects machine, a basketball inflater, radios, headphones, and a replay monitor.

“I hear all the time from people, ‘Oh, they got our trophy. They got our banners. They got Gary Payton’s jersey. They got all this stuff in Oklahoma City; how dare they?’” says Chris Daniels, a Seattle-based reporter for KOMO. “When, in fact, it’s never left Seattle. I get an email once a week asking, ‘When are the Sonics coming back?’ Occasionally one asks, ‘Where is the stuff?’”

Even if you knew precisely where to look, accessing the items is easier said than done. Even on MOHAI’s website, there are no immediate indications of any Sonics history.

A collections search of “Sonics” yields 22 results, a small fraction of the total archive, but an eclectic array of items such as a souvenir lunchbox signed by Payton and Rashard Lewis, a scroll with a handwritten Sonics poem and artwork from a fan contest, and a shirt and shorts signed by Nate McMillan after he appeared on an episode of Bill Nye the Science Guy.

McMillan, nicknamed Mr. Sonic, played 12 years in Seattle and spent another seven as an assistant and later head coach. The current Lakers assistant coach tells Front Office Sports he had no knowledge of the Sonics archive until a few years ago, when expansion chatter picked up: “I just heard that it was in storage. I didn’t know exactly where.”

McMillan has made multiple trips to Seattle in recent years but never considered visiting MOHAI to see the archive. He doesn’t consider any of its contents to be his property despite his connections.

To see the items, you must first make a request to MOHAI and state your intentions. Daniels says his pitch was reporting that might remedy the lack of fan knowledge about where the items have been all these years. Then, ironically, MOHAI must get clearance from The Professional Basketball Club, LLC, the umbrella company for Thunder ownership.

MOHAI has received only a handful of requests, mainly from the media, and the museum’s answer has never been no. The biggest issue is a logistical one given the size of some of the items. MOHAI is in possession of the six banners the Sonics hung in KeyArena for retired jerseys including Fred Brown, Lenny Wilkens, and McMillan. Occasionally, a diehard fan will make a request, but taking out a gigantic banner for one person is not sustainable if the floodgates open.

The museum has treated the Sonics memorabilia like any other artifact. Every item is cataloged in the museum’s archive and stored in climate-controlled environments.

“MOHAI has been an excellent steward to preserve and maintain the Sonics’ material,” Thunder corporate communications director Dan Mahoney tells FOS. “We have enjoyed a successful relationship with them over the past 17 years.”

While the settlement also allowed for the Thunder to occasionally borrow, display, or make copies of Sonics items, the organization has yet to do so in 17 years—consistent with a broader dissociation from its Seattle roots. Outside of the scattered fans in Sonics jerseys, Oklahoma City has the look and feel of an expansion franchise, not one that relocated.

Bennett retained the rights to the Sonics name and logos, but they’ve been missing in action since the move. If and when the NBA returns to Seattle, Bennett plans to turn over the logos, rights, record books, and, of course, memorabilia to the new owner at no cost as long as the NBA approves.

The items in MOHAI’s possession technically are on loan, though an expiration date would actually be good news. The agreement stipulated the collection “remains with MOHAI until such time as a basketball team or franchise returns to Seattle,” MOHAI executive director Leonard Garfield tells FOS.

Commissioner Adam Silver has hinted at NBA expansion multiple times in the past 10 years, only to blame the delay on the new collective bargaining agreement and media-rights deal, both of which are done. The recent Celtics sale led Silver to punt again, partially due to the exorbitant expansion fees the team’s $6 billion price tag created.

As the city waits for Silver to green-light expansion, owners and investors, including Seattle Kraken owner Samantha Holloway, await to submit a bid for the city.

In the bowels of Climate Pledge Arena, four stories below Holloway’s suite, sits a massive storage closet with a plaque on the entrance: “NBA Locker Room.” Holloway told FOS earlier this year that the wording was intentional, and that part of the plan for the Kraken ownership group was always to bring the NBA back to the arena.

For now, the Sonics’ history stays put, in a museum warehouse, where it’s been for the past 17 years, waiting for Silver and the NBA to allow it to be seen by the masses again.

“I just think that all of that stuff is important and I think it’s great that Oklahoma City didn’t just auction it off or do away with it,” McMillan says. “I think there’s a lot of people trying to rally the NBA to bring a franchise back there.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)