During a decade-long tenure, Mark Emmert spent most of his time attempting to resist changes to college sports. Ultimately, though, he just delayed the inevitable.

Emmert led a national office that spent millions fighting in court to preserve an increasingly unpopular amateurism model, even when public opinion had clearly changed. He dragged his feet on gender equity, and refused to lead on issues like the pandemic.

While his governing body has seen some court and NLRB victories over keeping athletes from being employees, he’ll hand off the reins just a few weeks after multiple federal judges questioned amateurism harshly in a hearing during an ongoing case.

- In 2014, he lost in court (with O’Bannon v. NCAA) and in state legislatures on preventing athletes from gaining name, image, and likeness rights.

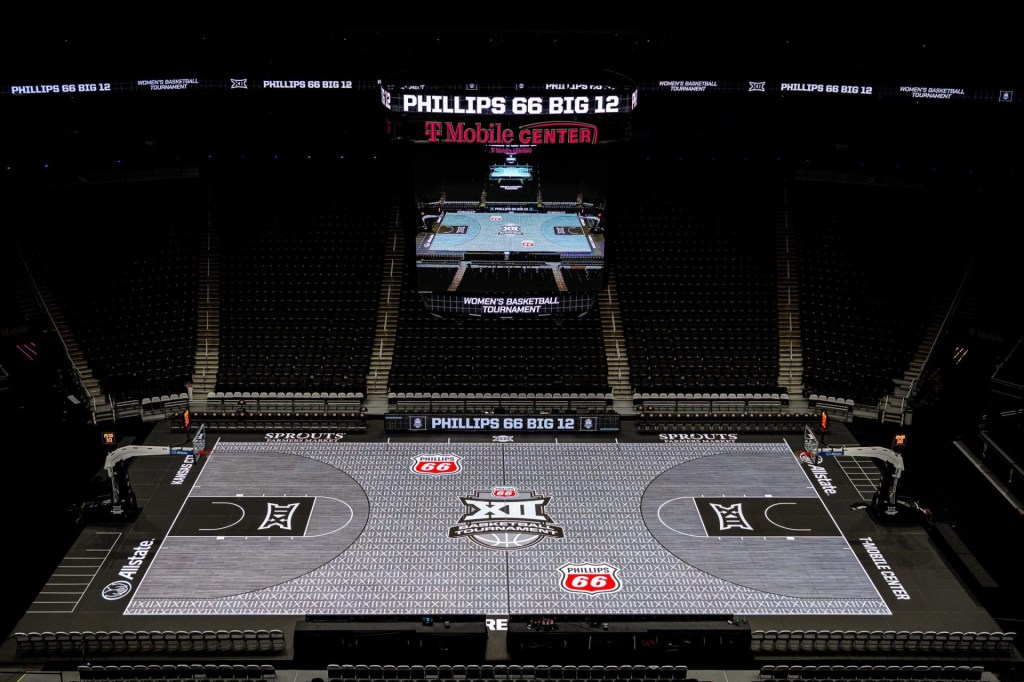

- The 2021 NCAA Division I men’s and women’s basketball tournaments — which took place in semi-bubbles due to the pandemic — put the NCAA’s structural inequities on the biggest stage.

- While he did eventually commission an in-depth gender equity review — which NCAA officials have begun to act upon — he only did so when forced. The review was commissioned 10 years after Emmert arrived at the NCAA, where structural problems existed without remedy.

- He then led the NCAA to the Supreme Court, where it lost 9-0 over whether the NCAA can limit athlete benefits in NCAA v. Alston.

The latter half of Emmert’s tenure can also be characterized by his silence.

During the gender equity fiasco, Emmert made excuse after excuse for the lack of marketing, promotion, and even gift bags and menu items that women’s basketball received — excuses he only offered after reporters cornered him in the halls of the men’s tournament.

He allowed his underlings, including NCAA VP of Basketball Dan Gavitt and NCAA VP of Women’s Basketball Lynn Holzman, to take most of the heat.

It was a similar approach to how he handled the COVID-19 pandemic — offering few, if any, statements about how schools should handle athlete safety.

And when the NCAA began to lose in court, he let his general counsel do the talking.

He was, however, an excellent scapegoat for decisions endorsed by university presidents, conference commissioners, and athletic directors. For serving as college sports’ bogeyman, the NCAA paid Emmert about $29 million in total.

As for what’s next, Emmert told Collegiate Sports Connect that he believes athlete employment status is the “absolutely the biggest issue” facing college sports today.

On Wednesday, Charlie Baker will assume the role. While he has revealed little about his personal opinions on various issues in college sports, he’s made one thing clear: His top priority is getting Congress to intervene on the NCAA’s compensation conundrum.

Baker, the former Massachusetts governor, was chosen for his reputation of building bipartisan coalitions and leading companies to financial success in the private sector. With the help of his former chief of staff, he’ll turn the NCAA’s national office into more of a lobbying firm than it has ever been.

Baker won’t move to the NCAA headquarters in Indianapolis so he can have more freedom to spend time in Washington. He’ll be asking Congress to codify what’s left of amateurism.