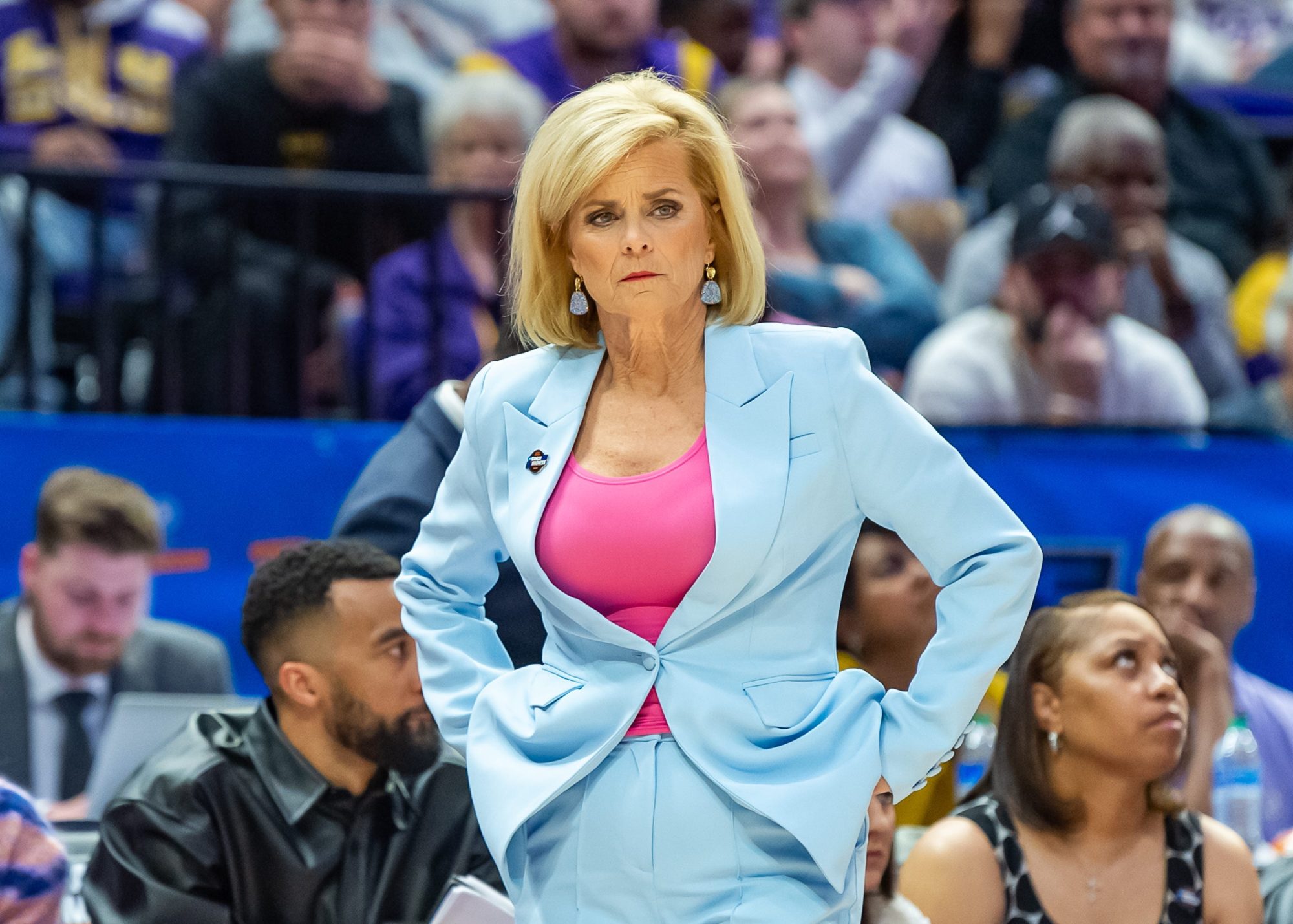

Over the weekend, LSU women’s basketball coach Kim Mulkey made a dramatic vow. “I will sue the Washington Post if they publish a false story about me,” she said, claiming to have hired “the best defamation law firm in the country.”

(Whether she’s actually done so is unclear; several of the country’s leading defamation law firms have not responded to Front Office Sports inquiries about whether they’re representing her.)

Undermining any potential defamation claim, Mulkey said that a Post reporter had approached her for comment but that she had declined to answer his questions. In fact, she said, she had told the reporter two years ago that she wouldn’t answer his questions because she “didn’t appreciate the hit job he wrote on Brian Kelly.”

As my colleague Margaret Fleming observed, the story, written by reporter Kent Babb, isn’t really a “hit job” and isn’t even about Kelly. The story mentions the Tigers’ football coach mainly in the context of juxtaposing the meager earnings of a Black LSU employee, as well as the impoverishment of the community surrounding the university, with his 10-year deal, which could pay him more than $100 million with bonuses.

“I don’t know why anyone would consider my 2022 story a hit piece, but I guess it’s all open to interpretation,” Babb told FOS via email. “I suspect most people who are complaining about the story never actually read it.”

That was the trigger point, in my book. (LSU didn’t respond to a request for comment.) There’s nothing that makes multimillionaire coaches at taxpayer-funded public schools go ballistic faster than being interrogated about—or, really, anyone critically mentioning—their swanky salaries and perks. We don’t know what questions Babb asked Mulkey and LSU. But I suspect his coverage of Kelly’s contract was the reason the fiery coach went off.

With four national titles to her credit, Mulkey is now the highest-paid women’s basketball coach in the country. After leading LSU to the national championship last season, the 61-year-old coach was rewarded with a 10-year extension that pays her $3.26 million per year. That’s more than Dawn Staley of South Carolina and Geno Auriemma of UConn, who earn $3.1 million a year. The coaching legend wouldn’t be the first, and won’t be the last, to have their ire raised by someone bringing up generous compensation.

Just a few months ago, Clemson football coach Dabo Swinney went on a five-minute rant after a radio caller questioned his 10-year, $115 million contract. “I started as the lowest-paid coach in this business [and] I worked my ass off,” Swinney told his radio listeners. “I’m not going to let this smart-ass kid get on the phone and tell me how to do my job.”

Who can forget former UConn men’s basketball coach Jim Calhoun’s heated exchange with a freelance journalist/political activist in 2009? When activist Ken Krayeske asked whether it was proper that the coach of a public university was the state’s highest-paid employee during difficult economic times, Calhoun vowed not to return a dime back.

“My best advice to you, shut up,” he said.

As Krayeske persisted asking about Calhoun’s $1.6 million annual salary, the veteran coach erupted. “Quite frankly, we bring in $12 million to the university, nothing to do with state funds. We make $12 million a year for this university,” shouted Calhoun. “Get some facts and come back and see me. … Don’t throw out salaries or other things. Get some facts and come back and see me. We turn over $12 million to the University of Connecticut, which is state-run. Next question.”

These questions are fair—and asked at times even by elected representatives. When Rutgers lured back former football coach Greg Schiano with an eight-year, $32 million deal in 2022, U.S. Rep. Bill Pascrell wrote a letter to the school asking why a coach should be the highest-paid state employee in history—not to mention Schiano collecting other perks such as a car stipend, clothing budget, country club membership, and personal use of private planes. “It is unclear how such lucrative compensation contracts further the overall educational mission of Rutgers and benefit your student body as a whole,” wrote Pascrell.

Earlier this week, I spoke with crisis PR expert Mike Paul about Mulkey’s confrontational approach. He gave her, and her LSU helpers, an F for media management. First, Paul noted, Mulkey only gave oxygen to a story that probably would have passed without much notice in the midst of March Madness. It’s no exaggeration to say that 100 times as many people could read Babb’s piece after her in-your-face press conference as would have without it. Maybe she doesn’t care. But she likely turned Babb’s story into one of the most-read feature stories of the year.

Plus, Mulkey continues to make things personal, referring to Babb and the Post as “sleazy.” I understand her frustration. She’s the type of pugnacious personality who likes playing offense, not defense. She’s a fighter. Respect to her. But her approach “definitely backfired,” Paul tells FOS.

“She’s trending for a reason. People are saying, ‘You’re giving us new information before it’s been out there. Keep talking. You’re the problem. And the way you’re handling it is wrong,’” says Paul.

Shannon Sharpe feels the same way about her reaction. “I probably wouldn’t have read it, but because she’s so animated, I’ve got to see what they’re talking about now. She’s got me interested,” said Sharpe on his Nightcap podcast with Chad Johnson.

The ultimate problem is that coaches like Mulkey want control. They want to control their players, their program, their media coverage. They can’t. During ESPN’s telecast of Monday night’s Pardon the Interruption, Tony Kornheiser—a longtime former Post columnist—said he did not expect Babb’s story to be defamatory.

“Kim Mulkey is a great coach, a terrific coach, and she sees the press as an enemy, which happens a lot in America these days. She is publicly defiant, she’s somewhat over-controlling. She does not want to be covered in a way that champions are covered, which is in-depth,” he said.

Kornheiser has a good point, especially since the legal standard for defaming a public figure like Mulkey involves, in most contexts, actual malice. This would be difficult to square with Babb, by her own admission, earnestly seeking comment from the coach. After all these years, Mulkey thinks she’s going to intimidate the Post? Good luck. Here’s the bottom line: The Post doesn’t work for you, Coach. Neither does the rest of the sports media. And those who wonder whether the best use of scarce public funds is lavishing millions of dollars on sports coaches aren’t attacking anyone, but simply exercising the prerogative of any citizen in a democracy.

Who’s Kent Babb?

The well-respected sports features writer is an unlikely candidate for the “sleazy,” tabloid muckraker depicted by Mulkey. Babb’s work has been included three times in the Best American Sports Writing anthology; won first place in feature writing three times from Associated Press Sports Editors; and authored two books, including one on former NBA superstar Allen Iverson. Babb has been working at the Post since 2012.

Despite Mulkey’s negative reaction to his Kelly piece, Babb says the story was not about the LSU coach. “My contention all along with the 2022 story is that it’s not even about Brian Kelly,” he writes in an email. “It’s really a look at one city’s vast economic gulf and what our society seems to value. Nobody did anything wrong here, least of all Kelly. I said it then and still believe it now: It’s just the sky-high cost of competing, and my only aim was to point out one extreme on the LSU pay scale and find someone who existed on the opposite end of that extreme.”

Babb heard from Post readers that he could have picked any high-profile coach lucky enough to cash in on the college sports arms races. That’s true, he admitted. “Many readers have said I could’ve chosen any college coach in the country, and I couldn’t agree more. I chose Kelly for two reasons,” he tells FOS. “The first is that he had just left Notre Dame for LSU and a contract worth a possible nine-figure maximum, and the second is that, just months earlier, my second book—about high school football in New Orleans, a city plagued by gun violence and corruption—had just been published, so I had an intimate knowledge of Louisiana’s political, racial, and economic disparities.”

Could Iowa-LSU Rematch Pull Record 10 Million Viewers?

Last year’s 2023 NCAA women’s basketball championship between Iowa and LSU pulled a record 9.9 million TV viewers. We’re getting ahead of ourselves a bit, but if the Hawkeyes and Tigers win their next games, they’ll meet in the Elite Eight.

The NCAA and ESPN are already dreaming about a possible rematch. Would Iowa’s Caitlin Clark get revenge on LSU’s Angel Reese for taunting her last year? Could LSU repeat as champs? Not to mention the soap opera around Mulkey and the Post.

I asked TV ratings expert Douglas Pucci if that rematch could set a new record for the most-watched women’s college basketball game. He thinks the game might peak at 10 million-plus viewers but ultimately come up short. “I will guess a still astounding average-per-minute audience to be 8.5 million,” says Pucci.

Michael McCarthy’s “Tuned In” column is at your fingertips every week with the latest insights and ongoings around sports media. If he hears it, you will, too.