In The News

Another week, another institutional investment from private equity (PE) in European sports.

This time, it was NHL team owner Bill Foley agreeing to buy Premier League club Bournemouth, but the last year has been jammed with headlines from deals — particularly involving Northern American investors — such as AC Milan’s with RedBird, Everton with the Soros family, Chelsea and Todd Boehly, and others.

Suggesting that this trend is exploding might be overstating, but we simply can’t ignore the recent influx of American PE and the rising interest from institutional capital in European sports.

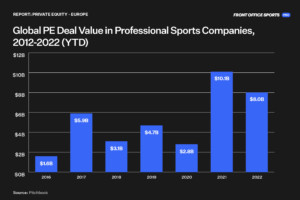

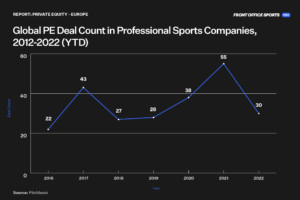

Data from PitchBook shows the global PE volume in sports properties this year has been close to 2021, with Q4 still to go.

Why are investors and European sports properties so interested in working with each other — and why now?

To understand those questions and identify the diverse challenges and implications of these deals, we spoke to Simon Chadwick, Professor of Sport and Geopolitical Economy at Skema Business School, and with Phelan Hill, Head of Consulting, West Region, at Nielsen Sports.

Here’s what they told us.

The Endless Pursuit of Alpha

For an investor, the main goal behind any investment is to find the opportunities that can yield excess returns (aka Alpha) with the least amount of risk exposure.

That’s even more important when surging inflation and rising borrowing costs force diverse sectors to take a more conservative approach and prepare for a slowing economy that might end in a recession or reduced consumer spending.

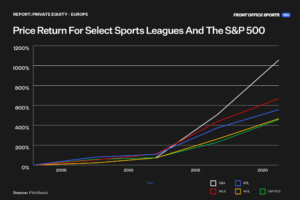

Data from PitchBook from the last two decades shows that the alpha generated from investments in the top-flight leagues in the U.S. has outperformed public markets significantly in most cases.

It is also rational to invest in growing industries. The rise of sports betting, NFTs, digital, and OTT streaming have increased the present value of upcoming media rights deals across sports leagues worldwide — solidifying the value proposition of investing in sports teams and leagues.

The opportunity for portfolio diversification through alternative and scarce asset classes with longer durations and lower risk has a status appeal to those with deep enough pockets to afford it.

Lastly — as with Fenway Sports Group’s strategy through Liverpool, the Red Sox, and the Pittsburgh Penguins — investment groups are looking to develop networks of influence within different sports across diverse regions to maximize exposure to future opportunities.

Meanwhile, sports properties are looking to maximize return on investment from capital backed with a strong institutional muscle.

After initially suffering from the pandemic and its resulting massive financial burden, recovering sports properties have become increasingly aware of the global interest in their products, the potential of new markets, and the value of commercialization opportunities overseas.

For example, The Athletic reported that the overseas rights for Premier League games will exceed the domestic for the first time in history between 2022 and 2025.

Some clubs are already making moves, and the rest are expected to follow.

- Bayern Munich focuses on digital content expansion to untapped markets like Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

- Manchester City has been implementing a global franchise network approach.

- Tottenham purposefully leverages its new multi-purpose stadium as an event destination and entertainment venue.

Acquiring institutional capital is cheaper and can offer opportunities for collaboration with portfolio companies, access to an international network, and increased availability of non-financial resources.

Teams can use the invested capital to build media platforms, create new competition structures, engage fans, and improve infrastructure, said Hill. Partnering with expert and global managers who bring complementary relationships and assets to the table will also be vital in reaching new markets and optimizing operations.

The European Dream

From the leftovers of the pandemic to the escalated tension between Russia and Ukraine — the macro environment has opened a window of opportunities to acquire stakes in European teams at a potentially once-in-a-lifetime discount.

The most distinct discount comes at a currency level, as the British Pound and the Euro are the weakest they’ve been relative to the dollar in more than 30 years.

But based on valuation multiples, European sports properties are also undervalued relative to American sports properties.

MLS clubs are valued at 12 times revenue on average, which is almost double the multiple in European football (6.2) and baseball (6.4), and greater than the NBA (7.8), said Hill.

For example, since 2017, the Buffalo Bills’ valuation soared 112.5% from $1.6 billion to $3.4 billion. The Dallas Cowboys are now worth $8 billion.

In contrast, Abramovich sold Chelsea for $3.2 billion, and the Saudis bought Newcastle for $415 million.

We could attribute this value differential to the commercial immaturity of European sports, explained Professor Chadwick. European club owners are less aggressive in developing and executing commercial strategies than U.S. sports franchises.

To many, the adjusted valuations derived from multiple macro conditions in Europe are beginning to seem like a bargain, but that doesn’t mean the investment and monetization process will be straightforward.

The Cultural Clash

The biggest challenge in the marriage between American capital and European sports might be the cultural contrast in how stakeholders from the different regions approach the industry.

Professor Chadwick explains that Europe has a cultural resistance to American capitalism because the DNA of European sport values its community, identity, family, and locality. Based on their standards, European teams are considered small and medium enterprises that do not necessarily see themselves as groundbreaking money-making machines like Google, Apple, or Tesla.

Even the biggest European clubs have a conservative history in their approach to monetization. For years, FC Barcelona refused to showcase any sponsor in their jersey until the club began realizing its potential and partnered with UNICEF in 2006.

It’s not that European clubs don’t have a vast appetite for profits, but it has not been a primary value in their history.

The upshot of this value clash is that European sports properties lag in the modern American approach of quick, fast money and aggressive profit-seeking within a free-market economy.

Hence, European sports properties and the different stakeholders will not necessarily be receptive to American-style innovations designed to bring in more revenue, at least in the beginning.

For instance, Liverpool head coach Jurgen Klopp recently mocked the new Chelsea owner Todd Bohely for his proposal to create an All-Star game, similar to the MLS, for the Premier League.

There will be a lot of pushback, and external investors may have to be patient. It’s a flash point — the marriage can work, but it’s more than likely to expect new challenges for both sides to reconcile the two successfully.

Europe also has a lower entry barrier for acquisitions than the U.S. leagues since the latter have established regulations that include bans on leveraged buyouts, limits, and conditions regarding ownership and financing — and only a few leagues have slowly allowed minority investments.

Nevertheless, due to some examples of European investment failures, these limits and regulations have a protective rationale.

The Dilemma: Scoring Goals or Focusing on Returns

Maintaining performance on the pitch is a massive catalyst for financial success in any club investment — a lesson some have learned the hard way.

- US investor Alan Pace acquired Burnley in a debt-financed deal in 2020, now facing financial struggles after dropping revenues estimates by around $112 million when poor performance relegated the team to EFL.

- American investor Ellis Short faced similar challenges in 2008 when he acquired a controlling interest in Sunderland. After losing £200 million in 10 years of poor performance, Short sold his stake in the club.

- Investors buying into Aston Villa and Serie A club Parma have also suffered similar fates.

New management will likely bring further questions to the table. The financial returns demanded from Americans will open the “performance dilemma,” where spending on the greatest players to maximize performance on the pitch might have to sacrifice future returns.

Hence, we can expect cynicism around the presence of foreign investors and higher resistance to change or clubs demanding higher prices to admit new investors.

Looking Forward

The sports industry is evolving and will require collaboration from both regions to maximize its potential.

European sports will look to generate profits following the American approach without harming the ethos of a long-standing culture based on conservative purity and authenticity.

American PE institutions and wealthy individuals will keep looking for stakes in European clubs while trading at a relative discount.

However — similar to most investments — there are risks involved. Teams still need to win, and prices and valuations may keep dropping or may take way longer than expected to grow.

Still, the marriage between the American capital and European sports seems like a practical solution during these turbulent times.