There are a few hurdles that remain.

Esports is the new big ticket item in the sports industry. Sponsorship revenue and acquisitions are at an all-time high, indicating positive expectations from all sides.

There are, however, skeptics — with some valid complaints. But esports has become one of the strongest candidates to become the next major sport in recent memory. That being said, esports is not without its flaws.

In order for it to get to that level, esports will need to overcome the following issues:

1. Monetization

2. Fragmentation

1. Monetization

There has yet to be a standard for monetization in esports, with a range of strategies varying from organization to organization.

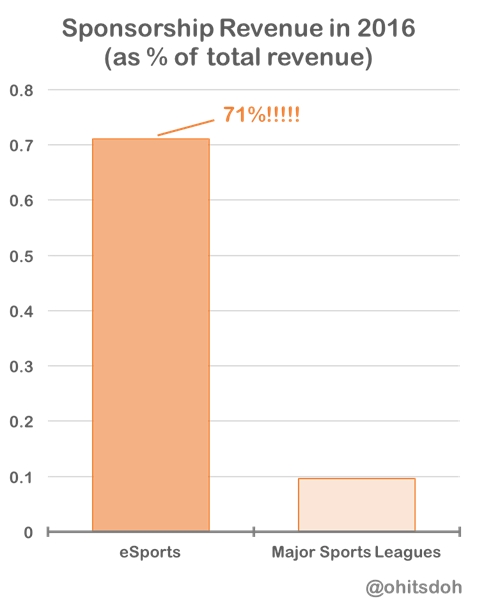

But throughout that, we’ve seen massive sales — such as the Philadelphia 76ers’ acquisition of Team Dignitas and Apex. It’s tempting to call it a bubble¹, especially when you see charts like these:

Where sponsorship comprises of 71 percent of all esports revenues.

The pervasive theme has been this: the acquisition of esports teams has been with the expectation of future growth, but unless esports finds another stream of revenue, it is unlikely to grow further.

For other major sports leagues, broadcast rights have comprised of a major portion of their revenue — a stream that esports has not yet tapped into.

With that said, the strategy for esports organizations has been very clear thus far: remove barriers to entry for first-time viewers, create affinity between fans and athletes, and monetize what you can through sponsorships.

And viewership numbers have, as stated here, have been vastly overstated.

“The reality is that it’s really hard to make an apples-to-apples comparison between Sports and esports viewership… The 43M Unique Viewers quoted by Riot for the League of Legends Finals is the TOTAL amount of viewers that watched the game for any given time — 1 minute or 3 hours. Not an average like Nielsen.

The 2016 League of Legends Finals had a peak of 14.7M viewers. That means at one given moment, ~15M people were watching. I’ll be very generous and let’s assume that the PEAK viewers was the actual AVERAGE over the entire game.

The Finals were between two South Korean teams — SKT and Samsung Galaxy. I’ll be very generous again and say that 50% of the US watched — but it’s probably much lower.

Taking those 3 factors into account, the relevant “Nielsen esports Viewership” for the 2016 League of Legends Finals would be 7M — NOT 43M.”

As much as some people would like to think otherwise, we’re still in the growth stage of this sport — and monetizing via broadcast rights would mean revenues for broadcast partners through one of the following:

a) Advertisements

b) Subscriptions

Where subscriptions create a clear barrier to entry for first-time viewers.

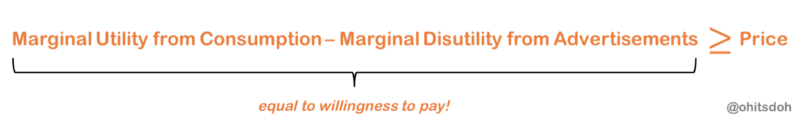

With regards to ad-supported content, as I outlined in my Tinder/Man U piece, users would consume where:

And it’s unclear yet if the marginal utility gained from consumption is enough to exceed the marginal disutility experienced from advertisements from first-time users — explaining the lack of advertisements for almost all streams.

2. Fragmentation

Successful sports leagues experience consolidation in almost all cases — consider basketball with the NBA and ABA, or baseball with the American League and National League. With multiple organizations running events, such as Major League Gaming (MLG) and the League of Legend Championship Series (LCS), esports is in its early stages as well.

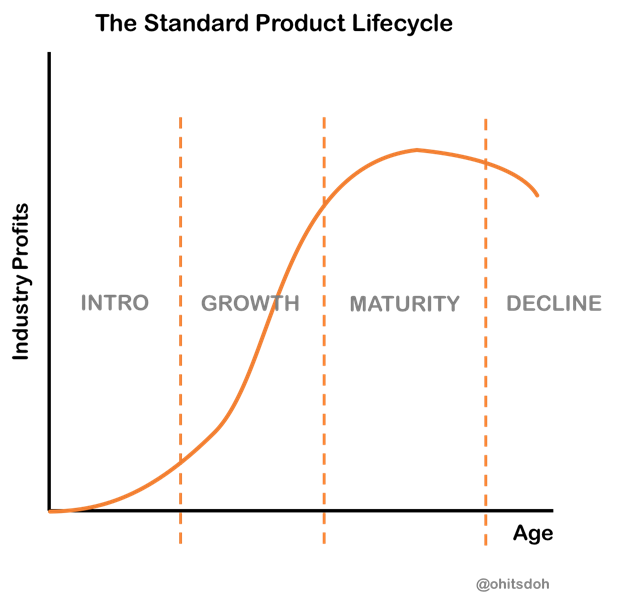

If we chart out the standard product lifecycle, it looks something like this:

Early on, there will be many entrants, with their own variant of the product. Over time, a dominant design emerges — and firms with the dominant design focus on reducing costs. This leads to the maturity stage, where dominant firms continue to sell more of their products, begin to consolidate, and product differentiation becomes less of a priority.

The same principles apply for sports — they begin with multiple organizations vying for market power, and when a dominant player emerges, with the dominant design (rules, broadcast strategies, etc.), mergers occur.

Put simply, strategic mergers are formed as alliances to boost the combined welfare of both parties. Similarly, sports organizations have the clear benefits of a cartel upon consolidation (i.e.: greater profits, monopoly power, economies of scale, etc.). At the same time, the product is also improved — there are defined rules, competitive balance can be maintained, athlete quality can be kept at a high standard (limiting number of entries), and league championships can be created.

Sidenote: Regional Monopolies

In esports, rather than an erosion of regional monopolies, we’re seeing an outright ignorance of regional monopolies. Compare this to traditional sports: where teams had “territories” — New York was Knicks territory, and the Packers had Green Bay. The result is a widespread fan base, rather than a focused one.

And this has translated to live broadcasts — where unrestricted streams are now the norm, with almost no geographic restrictions.

Where the distribution channels were formerly cable networks, the channels have shifted over to Internet companies, including YouTube (Google-owned), Twitch (Amazon-owned), and Facebook. This is something I touched upon in Sports, Streaming, and How ESPN Can Stay Relevant. In sports, regional networks, who (along with the teams) also had regional monopolies, contributed to a large number players in the space. Combined with the consolidation of attention and the shrinking number of worldwide distributors, we will see tremendous buyer power from these Internet companies.

¹ The definition of a bubble: when the price of an asset exceeds its intrinsic value ^

Front Office Sports is a leading multi-platform publication and industry resource that covers the intersection of business and sports.

Want to learn more, or have a story featured about you or your organization? Contact us today.