Embattled running start-up Grand Slam Track has narrowly avoided collapsing—for now—after receiving emergency financing from existing investors it used to make partial payments to athletes Friday, Front Office Sports has learned.

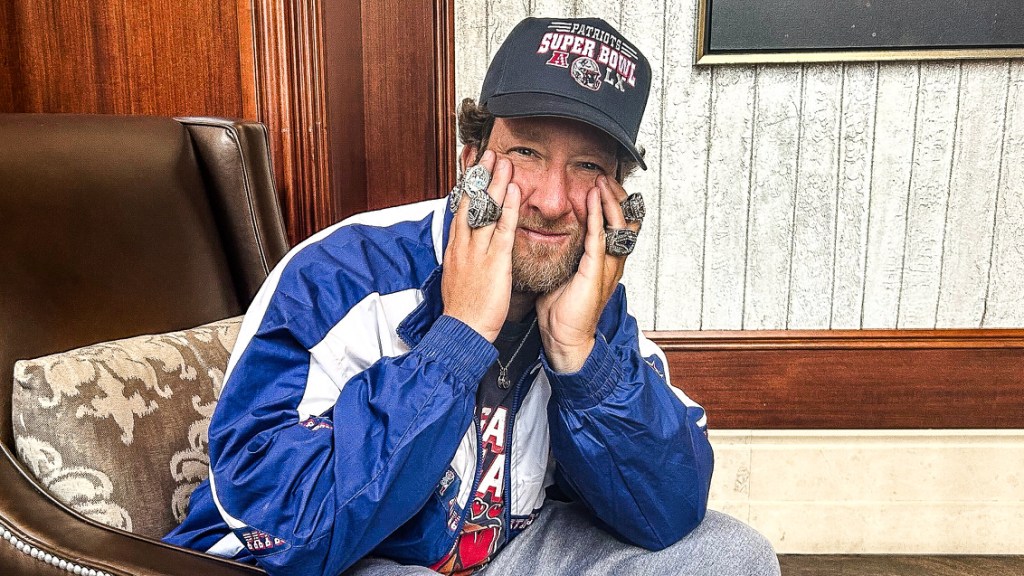

Grand Slam canceled its final meet of the year in June and owes about $19 million to athletes and vendors. Its founder, the Olympic champion Michael Johnson, said in August that Grand Slam didn’t have the funds to pay athletes, but he was still working with investors to secure funding for this year and the future.

Now, the league has the money to cover some of the shortfall. A handful of the start-up’s existing investors have provided the league with up to eight figures of emergency financing, a source close to Grand Slam tells FOS.

The funding is not enough to cover all of the league’s debts, which are about $11 million owed to athletes and roughly $8 million owed to vendors. But the league wired athletes half of what they are owed Friday and next plans to pay off some of its vendor debts. One athlete representative confirmed to FOS that the money had arrived early Friday morning.

The money also saves a few jobs: Grand Slam has fewer than 10 remaining employees, whose salaries will be covered by the emergency financing.

On Sept. 18, Grand Slam investors learned the league would be laying off staff the next day and beginning a state-level restructuring process, which is similar to but not exactly the same as a federal bankruptcy filing.

Some investors then expressed interest in putting additional funds into the start-up rather than letting it fail. Winners Alliance—the sports firm launched in 2022 by the Professional Tennis Players Association that led the league’s initial funding last year—set out to gather emergency financing of $5 million to $10 million from these investors for Grand Slam, and fronted the cash to keep paying the league’s employees in the meantime. Billionaire investor Bill Ackman, who chairs Winners Alliance, was supportive of the plan but was not heavily involved.

Grand Slam secured the commitments from investors at the end of September. The majority of the new cash, roughly $5.5 million, will go straight to athletes who are owed prize money and appearance fees from three events Grand Slam hosted earlier this year. The league says it will pay athletes half of what each is owed.

With the remaining emergency financing, Grand Slam will turn to vendors. Based on existing agreements, the league owes roughly $8 million for event and broadcast production, legal and accounting fees, and facilities payments. The city of Miramar, Fla., which hosted the Miami Slam in May, is owed $77,896 for usage of its track. The league is hoping to renegotiate those costs down, and it plans to distribute anything that remains after vendor payments to athletes.

Grand Slam sent an email Friday morning to explain the “installment payment” athletes received.

“Today is the beginning of Grand Slam Track’s reboot,” says the memo, obtained by FOS. “We apologize for frustrations and hardships caused by the payment delays to date. Over the next 60 days, we will be working hard to make things right with everyone who helped make 2025 a success, to best position GST for 2026 and beyond. This is a critical step in that delicate and difficult process, but know there is a path. Our appreciation of your grace and support as we walk that path cannot be overstated.”

A spokesperson for Grand Slam did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Winners Alliance declined to comment.

One agent said his client was still owed money from the Kingston meet, which most athletes had already been paid for. Another was pleased that the payments went out Friday. “It’s a huge step forward and credit to GST in fulfilling their promise to pay the athletes,” Ray Flynn, who represents Grand Slam stars like Josh Kerr and Cole Hocker, told FOS. “I have always maintained belief that [GST] would eventually pay.”

Grand Slam burst onto the track scene last year, proclaiming in February it had more than $30 million in funding led by Winners Alliance. The start-up said it would pay athletes a record amount of prize money—including $100,000 for first place—on top of a base salary or appearance fee. The start-up prioritized the athlete experience and sought to professionalize the sport, including by eliminating paper bibs, paying for airfare, and booking solo hotel rooms for athletes. It held three of four planned Slams in Kingston, Jamaica; Miami; and Philadelphia.

Cracks in the facade began to appear in Philadelphia, when Grand Slam shortened the meet weekend from three days to two, cut the 5,000 meters for both men and women, and did not fill open racing spots. The league then canceled its fourth meet in Los Angeles. In June, the company laid off about six people and cut the remaining staff’s pay by 15%.

Details about the league’s finances trickled out over the course of the summer. Johnson joined Front Office Sports Today in July, where he said an investor had reneged on a deal, which FOS reported was an eight-figure signed term sheet. In August, The Athletic reported the prospective investor was Eldridge—the firm led by Chelsea owner Todd Boehly, who is also part-owner of the Dodgers and Lakers—and that Grand Slam never actually had $30 million in its coffers. Athletes have been considering legal action, The Times of London reported last month.

Grand Slam said in early July that it had sent Kingston appearance fees to “all agents who have sent the appropriate paperwork.” Otherwise, the $11 million shortfall to athletes consists of prize money from the three Slams that did happen, and appearance fees from Miami, Philadelphia, and the canceled L.A. meet, which the league said it would still honor. The league missed a self-imposed deadline for the Kingston prize money at the end of July, and it had said its goal was to pay the rest of the money by the end of September.

As for swirling questions about next season, Grand Slam is still hopeful about 2026, the source close to the league tells FOS, but it must pay its debts first.