What if, with the tap of a screen, you could know how a fan at your venue was feeling? Could this help you make adjustments on the fly to better serve your consumer?

That’s what the University of Georgia athletic department is hoping will happen when it rolls out HappyorNot inside of Sanford Stadium this year.

The technology is fairly simple. Consisting of a terminal and four buttons that range from a very happy face to an angry face, fans are prompted to hit the buttons based on an experience that they had.

The goal is to be able to increase response rates from fans and to be able to react in real-time if needed to rectify a situation that may be causing dissatisfaction.

[mc4wp_form id=”8260″]

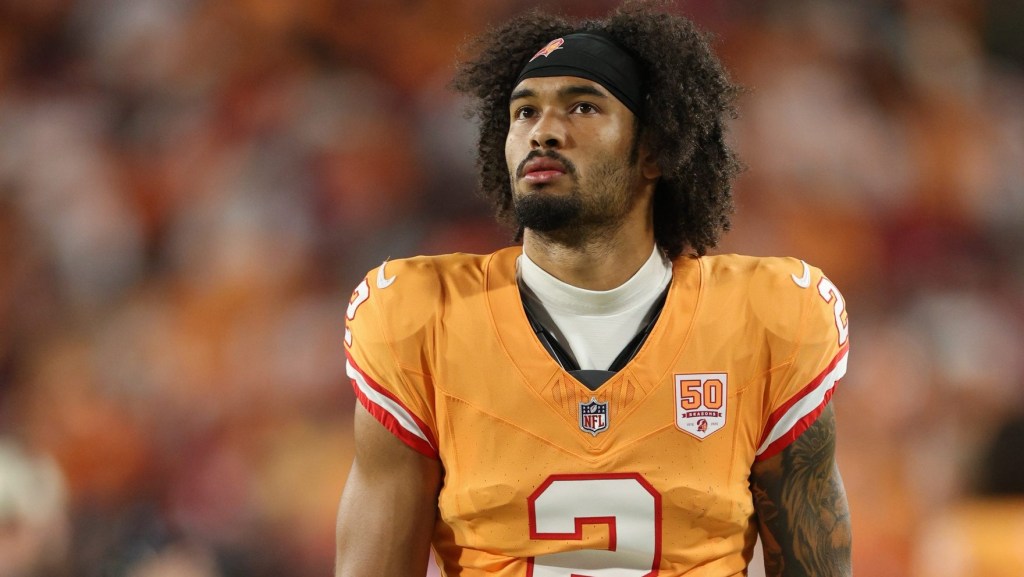

Having already tested the technology inside of Foley Field, the baseball stadium at Georgia, Deputy AD for Operations Josh Brooks is excited about what they will be able to learn come Saturday in Athens.

“We started with baseball this year with just a few units at restrooms and concessions stands and it went well. We were able to track the reporting over the course of the game and know for better or worse why certain restrooms and concessions were doing better than others.”

The idea to use the product came from an email that Brooks received from a donor. Between that note and a story he had read in The New Yorker, Brooks decided to conduct his own research on the company.

What he found was a simpler way to see how fans were really feeling at the moment and in the place they could have a reaction.

“This is a way to better quantify accurate results of people that are in your venue as opposed to people that respond to something because they had a really extreme scenario. We also don’t have to wait till the end of the year to interpret results and those results are then broken down by specific location, so I know exactly where things are going well or going bad.”

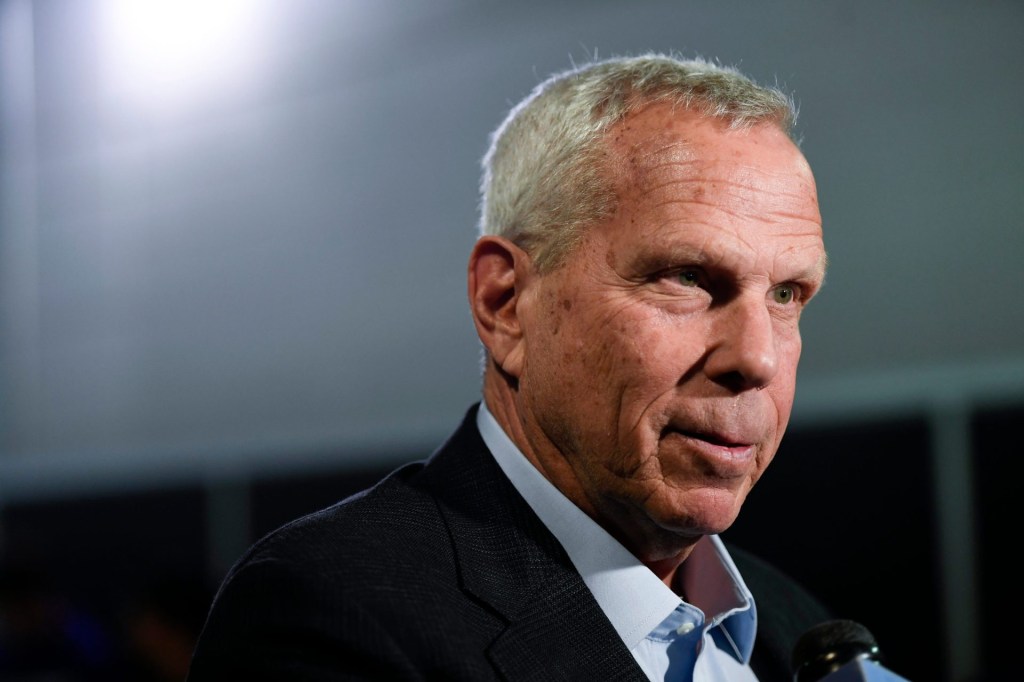

Outside of knowing how a fan is feeling or how their experience was, Brooks sees the technology as a way to keep people accountable, while rewarding those who continue to see impressive marks with different opportunities.

One of the groups he sees Georgia rewarding is the nonprofits that work the concessions during football home games.

“If we’ve got different nonprofit groups working in different concession stands, for example, and one of the groups are consistently getting higher scores than another, we could look at that and say ‘maybe this group deserves to be assigned a larger, more prominent concession area because they’re constantly getting better user ratings.’”

For the groups working the stand, this could mean more money to support themselves as most of these arrangements work by giving the nonprofits a percentage of the sales in exchange for them working the stand.

Instead of getting 10 emails from upset patrons in his inbox on Sunday and having to reply and then fix the problem for the next week, Brooks believes that the real-time nature of the technology (an app that refreshes every 15 minutes) will give him the chance to explore whether or not something is wrong as it happens, with his own eyes.

“I, myself, can physically go to that stand or restroom, determine the cause of the problem, whether there’s a spill or an overflowing trash can, and address the issue faster than ever before.”

[mc4wp_form id=”8260″]

Like any new initiative, Brooks and the team at Georgia know that while it’s great to have cool new tech, it can’t be a lipstick-on-a-pig-type scenario.

“Not only do we have to collect this data, we have to find ways to improve because, you know, collecting the data is just one part of it. If you collect it and don’t make improvements, what’s the point of collecting the data? So, that’s the challenge for us. We have this data; now what are we going to do with it?”