The Federal Trade Commission issued a final ruling Tuesday banning noncompetes, saying companies can, in many cases, no longer prevent their employees from leaving for a competitor. The FTC said current noncompetes for “senior executives” can stay in place, but no new ones may be enforced.

An estimated 30 million Americans have noncompetes, according to the FTC, and the clauses are littered all over the sports world. They stop coaches from leaving to do their same job for their team’s rivals. They’re in big contracts at retailers like Nike. They’re present in name, image, and likeness deals for college athletes. In February, DraftKings sued a former exec whom it alleges stole company secrets and took them to Fanatics as part of a “secret plan,” which the employee denied by calling the accusations “completely false and fabricated.”

Three sports lawyers tell Front Office Sports they found the FTC’s decision surprising and say it will have ramifications throughout the sports ecosystem, including pushback from both employers and employees that could wind up in court.

“With the elimination of noncompetes, what we’re going to see is much more movement of human resources around. And what that’s going to do is create some level, it would seem, of instability in a bunch of organizations you, John Q. Public, are very familiar with,” says N. Jeremi Duru, a law professor and director of the Sport and Society Initiative at American University.

Employers, however, aren’t going down without a fight. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, along with other business groups, sued the FTC within a day of the ruling, arguing that the FTC doesn’t have the power to ban noncompetes without Congress directly telling them to do so. Eugene Scalia, former president Donald Trump’s Secretary of Labor, represents another lawsuit from a Texas tax services firm, and more are likely to follow, experts say.

One of the most evident arenas for noncompete bans in sports is working for professional teams. NFL coaches are bound by the league’s Anti-Tampering Policy, which says assistant coaches can’t discuss another opportunity with a different team during the season, and they need team approval to interview with another club for a “lateral move” (taking the same job elsewhere) during the offseason. Examples abound of NFL teams restricting assistant coach movement. This offseason, after the Falcons fired Arthur Smith, they still blocked a handful of assistants from even interviewing elsewhere. It incensed staff. “They are blocking, but they are full of [expletive],” one anonymous source told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “They aren’t saying we’re keeping you, either. This is not what you do.” Niceties or not, it certainly is what is allowed under the league’s current rules.

The NFL did not immediately respond to questions about any potential changes to its Anti-Tampering Policy.

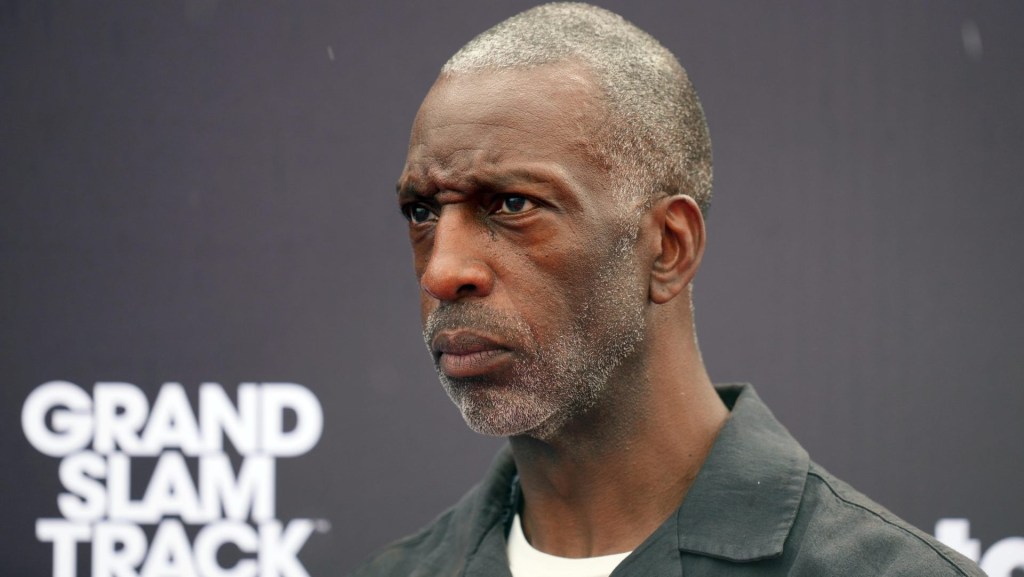

The policies extend beyond coaches to front offices. Bobby Marks, an ESPN analyst and former Nets executive, tells FOS that for most employees in NBA front offices, leaving for a promotion is allowed, but making a lateral move is not, barring exceptions like moving closer to family. Now, Marks says, there could be more flexibility to at least take an interview, which could give someone more money or job security, even if it’s a lateral move.

“Where in the past, you wouldn’t have been able to even get your foot in the door to see what that offer could look like,” Marks says.

Nellie Drew, a sports law professor at the University of Buffalo who directs the school’s Center for the Advancement of Sport, called the FTC’s ruling “jaw-dropping.” She says she questions what will happen to existing contracts that incorporate noncompetes now that the “basis of the bargain has been changed.” So does Duru, who expects to see litigation around this question.

“I think you’ll see a lot of lawsuits saying, ‘Hey, that’s dissolved, and now what I gave in consideration for that noncompete is something I’d like to claw back,’” Duru says.

Lateral movement is much more common in college sports, where noncompetes are rare in coaching contracts, but clauses restricting movement occasionally crop up. In 2004, Northeastern football coach Don Brown was supposed to get approval to negotiate or accept another job, but took off for Atlantic 10 rival UMass anyway, which cost his new employer $150,000 in a settlement and a three-game suspension for the coach. Bobby Petrino signed two contracts with Arkansas in 2007 and ’10 that included noncompetes to prevent him from coaching for another school in the SEC West and later the SEC entirely. To show his commitment to Illinois, current head football coach Bret Bielema suggested and included a noncompete clause in his contract preventing him from leaving for another Big Ten school.

In college contracts, buyouts often serve a similar purpose to noncompetes, but they don’t necessarily stop coaches from exiting a contract early, as showcased by the $100 million domino effect of Nick Saban’s retirement from Alabama. Still, top coaching contracts across sports that currently include noncompetes could take a page out of the college book. Drew says she expects higher salaries coupled with bigger buyouts to become more common to try to keep a coach from leaving.

Higher salaries, though not necessarily stricter penalties, are what the FTC intended with its ruling. The agency estimates that average workers will make an extra $524 annually with the ban, which is set to go into effect 120 days after it’s published in the Federal Register.

Drew also anticipates litigation to determine who owns information and relationships—a person or an institution. This can play out all over sports, from coaches carrying recruits’ contact information to agents who represent clients. Should a coach go to a new school or an agent leave for a new agency, do ties to their players or clients go with them or stay with their old employer? “Finding that delineation, I think, is going to be very challenging,” Drew says, adding that people will need to be more cautious with information knowing they can’t guarantee it will stay in-house, while Duru says eliminating noncompetes in an already-competitive agent world will have “substantial” impacts.

“It’s going to require a different perspective on a number of relationships that have had certain patterns of conduct for a very long time,” Drew says. “There will be a fallout. And how broad that fallout will be, I don’t think anybody really knows yet.”