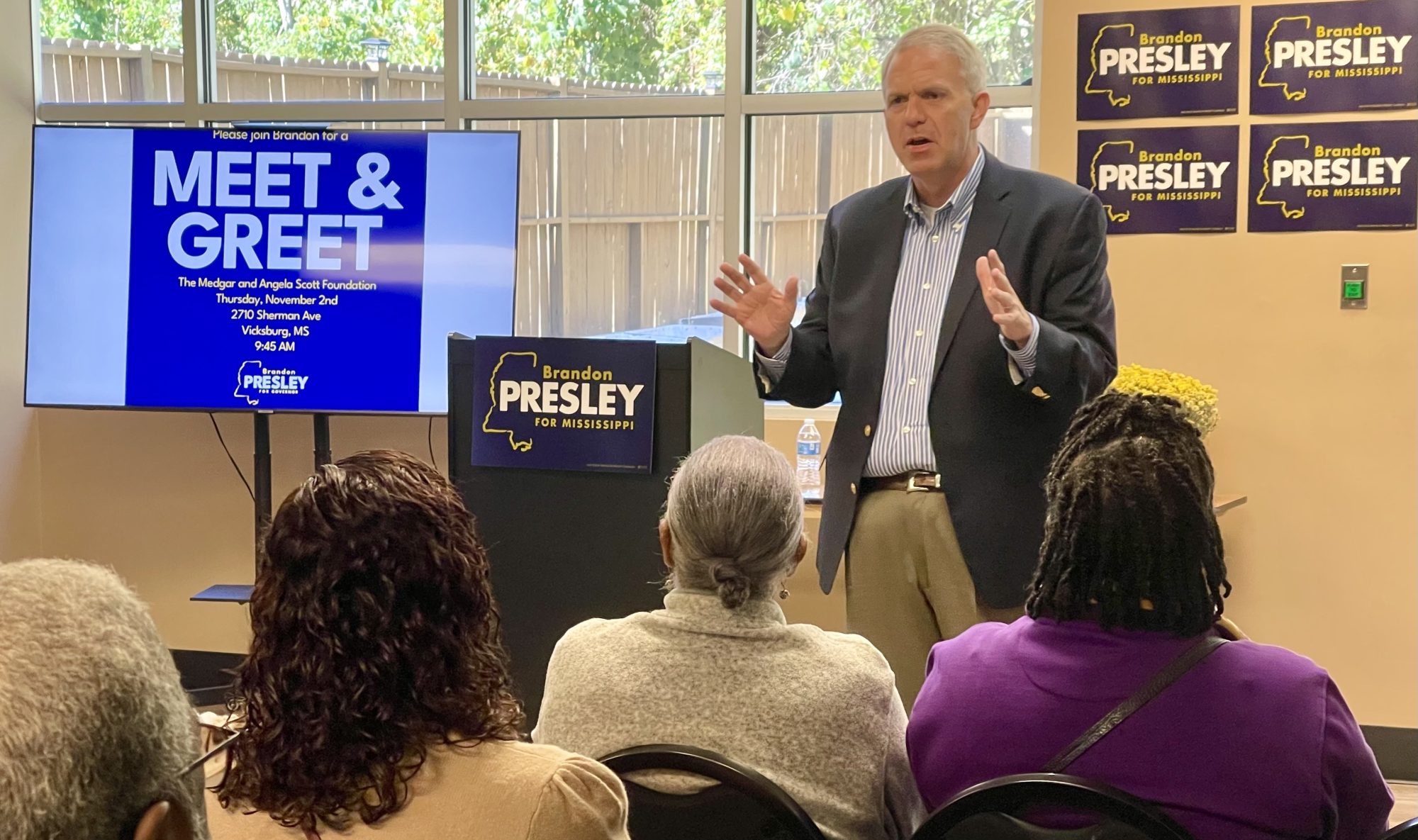

VICKSBURG, Miss. — Brandon Presley mentioned Brett Favre’s name. An overwhelmingly Black group of voters gathered inside Medgar, and Angela Scott Foundation’s headquarters on Thursday and responded with near-universal nods and one “that’s right.”

This was the Democratic gubernatorial candidate’s first campaign stop after Wednesday night’s debate with Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves, who finds himself in an unusually close race in the deep red state that hasn’t had a Democratic hold the state’s highest office in two decades.

“One of the things that got me into this race was that I had been working on getting running water for a family in Leflore County,” Presley told Front Office Sports. “They were catching rainwater in a boat so they could flush their toilets. It took us over a year to get that money so they could get some basic water service, but these jokers like Brett Favre can snap their fingers and get $5 million for a volleyball court. It just made me sick to my stomach. I hate the good ol’ boy network.”

Favre is still a somewhat beloved figure in his home state, where he was a prep football standout at Kiln before his legend grew at the University of Southern Mississippi en route to a Hall of Fame NFL career. Earlier in the campaign, Presley referred to Favre more as an “NFL star” or “celebrity athlete.” But Presley mentioned Favre three times during the only debate Reeves agreed to on Wednesday.

Presley has made the largest public corruption scandal in Mississippi history — and Favre’s alleged involvement — one of his top talking points along with Medicaid expansion.

”I think those are the two issues that voters are going to have on their minds on election day,” said Presley, a cousin of Elvis Presley, who is in his fourth term as a member of the Mississippi Public Service Commission. “Medicaid expansion is a proactive step to get healthcare to 230,000 working people, but corruption also has people here mad as hell.”

Favre is one of 47 defendants in the lawsuit filed by the Mississippi Department of Human Services as it seeks to recoup at least $77 million of misappropriated federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds, money that is supposed to aid the poorest people inside the poorest state in the country.

About $8 million of those TANF funds were directed to Favre and his pet projects, including about $5 million for a volleyball center at his alma mater and where his daughter played the sport at the time. The TANF funds for the volleyball center the Favre lobbied then-Gov. Phil Bryant and others were funneled to the Southern Miss Athletic Foundation, which is also a defendant in the MDHS civil case.

Favre has denied any wrongdoing and has not been charged criminally.

Dale, who declined to reveal his last name, told FOS that the public corruption scandal is the “major” reason Black voters like himself are voting for Presley — even if Reeves wasn’t directly involved in it as governor.

“They knew what they were doing from the start,” Dale said after Presley’s stump speech. “Even though at the time that Tate was the lieutenant governor and Phil Bryant was the governor, they should have stood up for what was right for Mississippi, what was right by the law, and not look toward helping their rich friends and their rich buddies.”

Reeves served as Mississippi’s treasurer and then lieutenant governor, a stint that occurred as the TANF scandal played out. It wasn’t until after Mississippi State Auditor Shad White initiated an investigation in 2019 — after then-Gov. Bryant alerted White’s office of the possibility of the TANF funds being misspent — which led to a series of criminal indictments for those involved in the scheme, including John Davis, who led MDHS at the time.

“You would have to believe in time travel to believe that I was involved in the TANF scandal,” Reeves said during the debate. “The fact of the matter is, it all happened before I was governor, between 2015 and 2019. Brandon Presley knows that, but just like he’ll lie about my family, he’ll lie about me; he’ll lie about everything.”

Presley countered with the firing last year of Brad Pigott, the former U.S. Attorney who oversaw the lawsuit originally.

“You fired him when he got a little too close to your buddies, … a little too close to those people in your inner circle,” Presley said.

Presley also took a prop out of his jacket pocket during the debate, a printout of text messages that Reeves’ campaign released weeks ago. Reeves’ brother, Todd, messaged White, “Brett has done nothing wrong,” and he was repaying the $1.1 million of TANF funds Favre received for appearances he didn’t do “from his own good will.”

FOS left messages with Reeve’s campaign and the governor’s office spokespeople seeking comment for this story, but they did not return the messages.

There hasn’t been a full reckoning regarding the TANF scandal. Davis is one of just two state officials charged by authorities. The lawsuit has progressed slowly, and they will not depose Favre until next month. So far, only a fraction of the TANF funds have been recovered. The GOP-led state legislature hasn’t called a single hearing on the matter.

“Whether you believe Reeves is involved or not, his name has been thrown into this,” said Greta Kemp Martin, the Democratic candidate running for Mississippi attorney general. ”His brother’s name has been thrown in. Why is Reeves calling the shots on who is running the investigation? Why is he the one that hired [the outside law firm] Jones Walker? Why is he the one that fired Brad Pigott? Why is the AG’s office not handling the hiring and firing of outside counsel?”

Kemp Martin, whose incumbent opponent Lynn Fitch refused to debate her, told FOS that the welfare scandal has been a significant driver for those seeking statewide office this election cycle. Like others in Mississippi politics, Kemp Martin said Presley’s outreach to Black voters — 70% of who didn’t vote in 2019 — could prove to be the difference come Tuesday.

This is the first statewide election since the state legislature finally eliminated the Jim Crow-era statute that mandated that a candidate not only win the popular vote but also the majority of Mississippi’s 122 House districts. But another law put on the books back in 1890 — which permanently bans many convicted felons from voting — is still in place, something that impacts about 16% of Mississippi’s Black population.

“Absolutely voter manipulation and voter suppression still exists,” Shawn Jackson, a member of the Warren County Board of Supervisors, told FOS. “We are factoring it in. We got to turn out Tuesday. We have to keep turning out.

“I think timing is the biggest force [for Presley]. The wind is at his back. When you elect the wrong people, corruption can keep going. I believe incompetence has a short runway, and I think that runway is at its end.”