Don’t look now, but the Ball family might be onto something.

LaVar Ball can be a perplexing character, and when he announced the launch of Big Baller Brand, and its inflated price tags, the NBA community collectively groaned.

In a vacuum, a lot of this doesn’t make a whole lot of sense: primarily because shoe brands have historically provided fantastic value to entry-level NBA players, for which the music industry is a fantastic analogy.

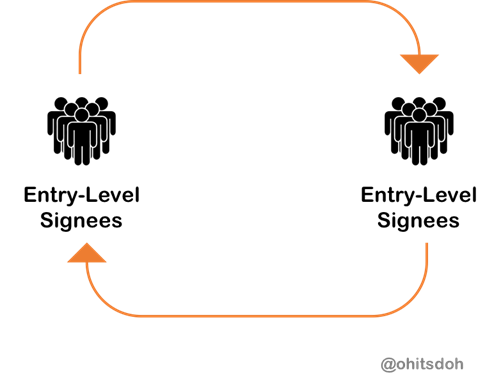

In the much-maligned music industry, record labels sign many talented young musicians for multiple years with the expectation that most will fail, but a few will succeed. The labels then fund marketing, PR, recording, concerts, and take advantage of their scale and connections to distribute lots of music as a single buyer — reducing unit costs.

In other words, the label takes care of everything but the performance itself, and is damn good at it because it’s big. For the label, this makes sense because the success of a few artists can fund the success of future artists.

The artists benefit because for the average entry-level signee, they are having an entity fund their career (essentially acting as an angel investor), without having to pay any money out of their own pockets.

The difference in the NBA is that everyone gets a deal — from superstars, all the way down to D-Leaguers. Where record labels act as angel investors, brands like Nike or Adidas would act as venture capitalists, since money comes in at a later stage, meaning that success is much easier to predict. Similar principles hold: the brand takes care of everything when it comes to selling the shoes, leaving the player to focus on his on-court play.

For young players, who are on their rookie shoe deals, and with a limited personal brand, endorsers have all the leverage — and can afford to pay them less than their eventual value. Lonzo, who was offered up to $15M over five years (including incentives), would be under his rookie shoe deal until 24 — taking him into the early prime years of his career, and his peak sales years.

Big Baller Brand’s assumption is that players are underpaid for their contribution to shoe sales. For 2014, LeBron James, the highest-paid active NBA player in sneaker money, was paid $32M, with his sneakers selling $340M in revenue — meaning that his Nike contract paid him just under 10% of his shoe revenue.

To pay their players more money, the brand would have to cut into their margins — relatively large for LeBron’s signatures, which are priced as luxury goods.

The competitive advantage for BBB is unknown to this point, but so far it seems to be banking on brand, which is indeed one of the strongest differentiators in fashion. All things equal, the same sales for an above average brand will trump the sales for an average or below average brand. The problem here is that all things are not equal — BBB shoes are being sold at 3x the cost of the average shoe.

The Ball Family Package

A lot of criticism comes from fans observing BBB in the context of the modern shoe economy. For Nike or Adidas, of course it would make no sense to sell a rookie’s signature shoes for $500. Of course an average looking shoe with a big price tag would sell less than 400 pairs the first week.

But for BBB, the shoes aren’t the core product. The point of their shoes, and its entire point, is to act as a tactic for their overall strategy — which is to drive total celebrity brand (and in turn, increase overall profits).

If there are two parts to a player’s paycheck, characterized by his on-court play and off-court brand, the off-court brand had traditionally almost entirely been managed by his sneaker brand. This made sense in the context of 20th century economics — where the endorsing company was the principle mechanism of providing off-court exposure to the athlete’s brand. Brands had the distribution network and marketing dollars that athletes did not have access to.

So, while players’ performance drove sneaker sales (Exhibit A: the high correlation between team performance and their star players’ signature shoe sales), sneaker brands also pushed their brands forward: creating a symbiotic relationship.¹ In addition, most players derive tremendous utility through celebrity and brand — which has driven the popularity of large markets as free agent destinations.

And this model has worked well for all parties! Because sneaker brands are incentivized by making more sales, they will naturally market the players — because a popular player would create a popular shoe. The best example of this is Michael Jordan, whose status as a worldwide superstar could largely be credited to Air Jordans.

Here’s the thing: in most cases, sneakers did not drive first-time awareness to players. Fans bought sneakers because they were fans, not the other way around. But sneakers also increased exposure and affinity — the importance of the former being that the brand was being brought off the court, and the latter creating the most important type of customer: a loyal one.

In the context of the modern economy, however, with the rise of the Internet, and fall of retail, we’ve observed two things:

1. The declining value of a distribution network

2. The democratization of advertising and content

The Declining Value of a Distribution Network

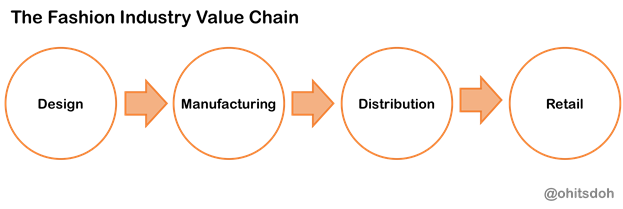

Put simply, the fashion industry value chain looks this:

Which meant that, pre-Internet, manufacturers had little option when it came to retail — brick and mortar were the only way to reach the customers.

For manufacturers, the scarce resource was shelf space — meaning that developing a relationship with retailers was paramount to getting their products in consumers’ line of sight. And selling retailers a massive number of products was certainly helpful in developing this relationship.

Since the rise of e-commerce, we’ve seen the rise of a suitable alternative. The Internet, which can be in all places, with an infinite amount of shelf space, has provided manufacturers with the ability to sell to consumers via a method other than brick and mortar retailers. This benefits primarily smaller brands, who need not develop a relationship with retailers any longer.

This relationship between manufacturers and retailers has only just started to manifest itself. Take, for example, Foot Locker, which has been disappointing investors with a recent 25% drop in share price. CEO Richard Johnson placed the blame firmly on Nike — which comprised of approximately 68% of their products (page 26).

The Democratization of Advertising and Content

Like distribution networks, what we are now observing in both advertising and content is the shifting of scarce resources. Where, in the context of television, the scarce resource was time and capacity (there are only so many channels!), the Internet offers limitless possibilities, at zero cost.

The power of large brands, again, were the relationships they had developed and the scale efficiencies of working with agencies who would buy ad spots. Since a large part of exposure is now only being driven by two mediums (Google and Facebook) with low barriers to entry, athletes now have direct access to consumers.

What LaVar has displayed is a complete disregard of traditional mediums — preferring to attract press via his bravado and ludicrous statements, which have been dispersed via the Internet. Versus Nike’s inflated marketing spend, Big Baller Brand’s belief is that they can drive similar amounts of traffic to their brand at little cost to their overall brand.

The key here is not to question whether or not LaVar’s methods are able to reap the same returns that traditional mediums have: it’s that there is an alternative at all — something that athletes had never had.

The Shift for Brands

At the crux of this decision is LaVar Ball’s desire to bring the control of their brand in-house, and not have to rely on an agency force to manage much of their off-court image. The Balls, who have eschewed traditional mediums of distribution, retail and TV, have now focused on an Internet strategy — and pushing forward the Ball name by any means necessary.

We may also be observing a new phenomenon in sneaker endorsements — where the timing of funding may be shifting for the most elite prospects. The value of sneaker deals is not predicated on performance, but is predicated on brand, which culminates in expected number of sales.

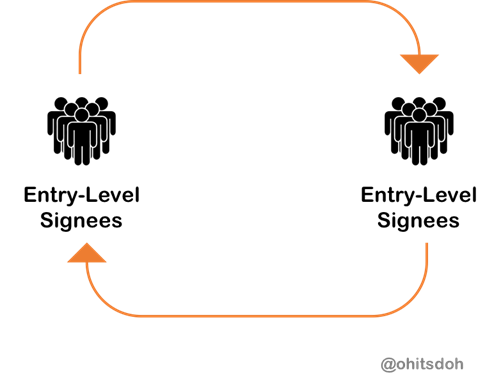

For athletes entering the NBA with more hype than ever before, the result of this is a need for larger endorsement deals — leading to either more expensive shoes or a diminished margin for retailers. It also reduces brands’ leverage for the most elite prospects, meaning that this diagram:

Where a few successful athletes fund future athletes, starts to shift. What was formerly a good deal for rookies starts to look less valuable. If the rate of increase in celebrity branding surpasses that of sneaker deals, more athletes may take the Ball family route.

The Ideal Path

My take: The Balls, who have immediately taken the “build your own brand” route, will likely experience some kind of success in their approach. As Jeremy Fitch wrote here, there’s a lot to like about their overall package: which includes a reality TV series², distributed via Facebook.

Even so, the ideal strategy would have been to take a shorter contract — instead of a five-year, a two-to three-year contract — letting Nike or Adidas take care of building the Ball brand, while also receiving what would still be disproportionate value, also leveraging a distribution network that encapsulates the entire globe. If Lonzo experienced success, he could spin off his own brand that would include the rest of his family.

There are two possible scenarios here:

1. BBB could become a success, and LaVar is lauded as a visionary.

2. BBB influences a wave of young NBA stars looking to pave their own way.

To be honest, I think that either scenario could be called a success. In 1., the Balls make a boatload of money, and in 2., they can find comfort in the fact that they ushered in an entire era of entrepreneurs, at the expense of big corporations.

That’s why I say this: it’s early, but LaVar’s marketing has been successful thus far. Tell that to the average NBA fan a few months ago.

¹ What I’m proposing is not that sneaker brands were solely responsible for athletes’ popularity. The highest selling shoes, generally, belong to the most talented and exposed players — meaning that on a relative scale, star players are now at the same level. But sneaker brands now drive a huge portion of absolute popularity, which leads to incremental revenue and an improved off-court brand. This can almost be an application of game theory — where everybody needs to have an endorsement, lest they lose popularity to their peer with an endorsement. ^

² Sadly, our favorite brother, LiAngelo, is missing from the picture. ^

This piece has been presented to you by SMU’s Master of Science in Sport Management.

Front Office Sports is a leading multi-platform publication and industry resource that covers the intersection of business and sports.

Want to learn more, or have a story featured about you or your organization? Contact us today.