President Joe Biden gave former University of Miami booster Nevin Shapiro an early holiday gift.

On Thursday, Biden commuted Shapiro’s 20-year prison sentence as one of nearly 1,500 handed down, a single-day record for a U.S. president.

Biden did not release a statement specific to Shapiro’s case, but the White House made a statement about the record amount of commutations.

“As the President has said, the United States is a nation of second chances,” the statement read. “The President recognizes how the clemency power can advance equal justice under law and remedy harms caused by practices of the past.”

Shapiro, who illegally paid University of Miami football and basketball players for nearly a decade in the 2000s, was convicted of securities fraud and money laundering in 2011, charges stemming from a $930 million Ponzi scheme he ran from his company Capitol Investments USA in Miami. Shapiro claimed to buy wholesale groceries and sell them to more expensive markets, though it turned out he never sold them. Shapiro used Capitol to solicit the money over a four-year span from investors who thought they were getting a stake in his grocery distribution business.

He received a 20-year sentence in June 2011 and served time in prison until 2020, when he was transferred to house arrest due to COVID-19. Shapiro was ordered to pay more than $82 million in restitution to his victims.

Shapiro has about six and a half years left on his sentence, and it’s unknown by how much Biden’s commutation reduced it. (Commuting a sentence reduces it, while a pardon is a total forgiveness for a crime and removes all legal penalties. A pardon can restore certain rights based on the nature of the crime.)

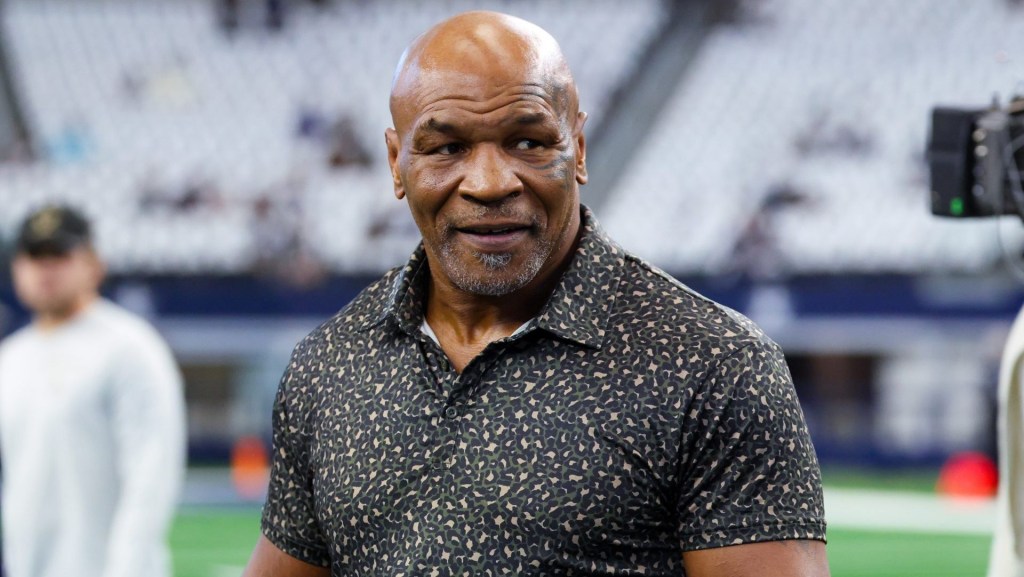

While under house arrest, Shapiro has emerged as an online personality, appearing on Miami-related podcasts and posting videos to his Instagram account. Shapiro calls himself “Original N.I.L” and “Former University of Miami Rainmaker” in his Instagram bio. The “former” is a nod to paying college players, which has since become legalized; NCAA bylaws began permitting athletes to make money off their name, image, and likeness in 2021. The “rainmaker” moniker refers to his reputation for taking Miami athletes to nightclubs.

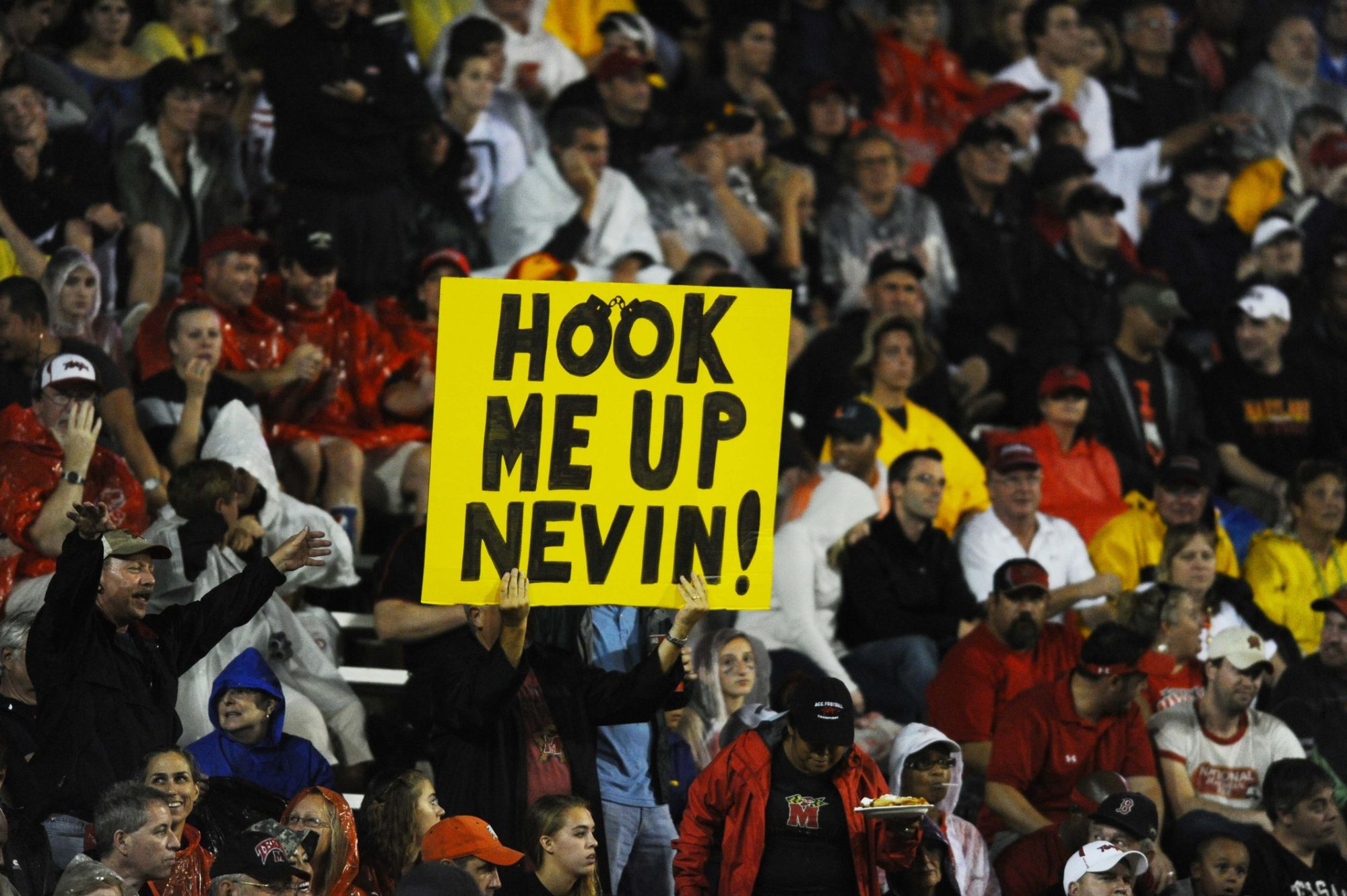

In the early 2000s, few people were as powerful in Miami athletics than Shapiro. He was allergic to following NCAA rules. He regularly cut checks to the Hurricanes while entertaining their star players—illegal activities at the time. Occasionally a Miami athlete, including former Hurricanes and NFL star Vince Wilfork, signed with Shapiro’s agency, Axcess Sports, when they turned pro.

Two months after being sent to prison, Shapiro disclosed his behavior in an interview with Yahoo Sports, which exposed the athletes he paid, the university, and himself. In light of Shapiro’s revelations, the school imposed significant penalties on itself in an attempt to mitigate major punishment from an NCAA investigation. It imposed a postseason bowl ban on itself for a year and suspended eight members of its football team.

The NCAA launched its own investigation, which took two and a half years to complete after it was revealed NCAA investigators broke their own rules by paying Shapiro’s lawyer to call university personnel for a deposition related to a separate case regarding Shapiro’s bankruptcy and using it to ask questions about his scandal with the athletic department. Shapiro’s lawyer used her subpoena power in the bankruptcy case, which the NCAA lacked on its own, to question two witnesses who were also tied to the NCAA’s case.

Ultimately, the NCAA punished Miami by docking three football scholarships for three seasons, putting the program on probation for three years, imposed recruiting restrictions, and suspended former coach Frank Haith for five games. Haith served the suspension as coach of Missouri.

While Shapiro went to jail for his Ponzi scheme, he never faced charges for his role in the Miami scandal. But the situation and the NCAA’s handling of it showcased the lengths schools went to win, how institutions looked the other way on rule-breaking, and how the NCAA wasn’t competent enough to enforce its own rules.