Twenty years ago, Victor Conte was neither famous nor infamous.

On Sept. 3, 2003, his Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (BALCO) was raided by federal agents, and within months, he was part of the biggest doping scandal in U.S. history — even if the money seized that day, and the minor punishments that followed, didn’t amount to much.

“The grand total in value of all the drugs they confiscated was $1,720,” Conte told Front Office Sports. “This is consistent with personal use, not the fueling of an international steroid distribution.”

It was the players’ names — predominantly Barry Bonds’ — that drove the hype. BALCO instigated a national conversation on steroids in sports, and kept Bonds and the many others linked to PEDs in the years to come, from Roger Clemens to Mark McGwire, out of Cooperstown.

One person was chiefly responsible for that: Jeff Novitzky, the IRS agent who led the investigation. As he did in real life, Novitzky plays the foil to Conte in Netflix’s “Untold: Hall of Shame” documentary, which debuts Tuesday.

“There is no doubt that [Bonds] used performance-enhancing drugs and used a lot of them for a several-year period that assisted him in achieving those hallowed records in sports. Without a doubt,” Novitzky said.

The Long Ball

Bonds was already the single-season home run champ by the time BALCO became part of the sports lexicon. His 73 homers in 2001 came just three years after McGwire and Sammy Sosa battled to surpass Roger Maris’ 61 set in 1961.

McGwire, who hit 70 home runs in 1998, denied he used PEDs all the way through 2010. Sammy Sosa, who hit 66 that year, was among the 89 names in the Mitchell Report detailing baseball’s steroid era, although he’s never admitted to using PEDs.

Bonds played under a cloud of suspicion as he surpassed Hank Aaron as the all-time home run champ in August 2007. He finished his career with 762 home runs.

“Obviously I really, really wanted to talk to Barry Bonds,” said Bryan Storkel, the director of the documentary. “We wanted to tell some new parts of the story, and just in more detail and more comprehensive than before.”

Storkel succeeded by showing viewers the doping calendars kept by Bonds’ personal trainer Greg Anderson. Conte himself said he’d never seen the calendars purported to show Bonds’ doping schedule.

Bonds denied he knowingly used steroids when he was subpoenaed by a federal grand jury. He was charged with perjury and obstruction charges for his testimony, and a jury returned one guilty verdict for obstruction in 2011 — a charge eventually overturned on appeal.

A major issue for the feds was that those doping calendars couldn’t be used in court — because Anderson refused to cooperate, they couldn’t be authenticated. Beyond the three-month stint from the BALCO indictment, Anderson twice served time for contempt for refusing to cooperate with investigators.

Conte has long denied that he supplied Bonds with “the cream” (testosterone), “the clear” (a designer steroid undetectable in drug testing at the time), or any other banned substances. Conte did, however, provide both to Anderson.

“Do you want to guess if Barry Bonds took steroids?” Conte said in the documentary. “I think it’s likely.”

What Happened To Designer Steroids?

“The clear” developed and supplied to BALCO by chemist Patrick Arnold remains the most notable — and last — designer steroid to become an issue in sports over the last two decades.

“Everybody was saying, where’s the next designer coming from?” Conte told FOS. “Where is it? I was one of those people — and there hasn’t been a single [expletive] one.”

It’s not that athletes aren’t doping. Conte said the percentage of athletes beating doping protocols hasn’t changed from when his lab in San Mateo, California, was raided.

“Are they still using PEDs?” Conte said. “Yes, they are.”

Conte said athletes are using substances to increase performance — like human growth hormone (HGH), Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1), and erythropoietin (EPO) — that are made in the body naturally. The tests to detect whether an athlete is using a syringe to give their bodies a boost aren’t as reliable as traditional steroid screenings.

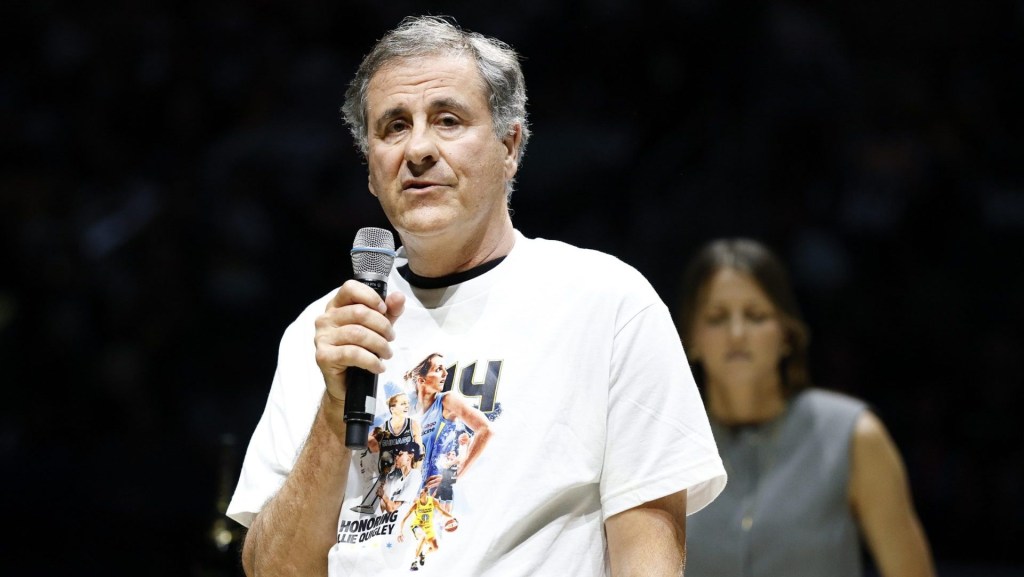

And despite all the hype from nearly two decades ago, Conte received four months in prison plus four months of house arrest. Two others — BALCO exec James J. Valente and track coach Remi Korchemny — received probation.

Counting Anderson, the original BALCO indictment resulted in just seven months served among the four charged.

One factor is that the government could not prove “the clear” was an anabolic steroid. Mary McNamara, one of Conte’s lawyers, described the amount of drugs as “teensy” in the documentary as she and law firm partner Ed Swanson managed to get 40 of those 42 counts against Conte dropped.

‘Victor Is Quite Bright’

Conte and his lawyers talked up what a great overstep the investigation was, although Storkel let Novitzky get a few jabs in the doc.

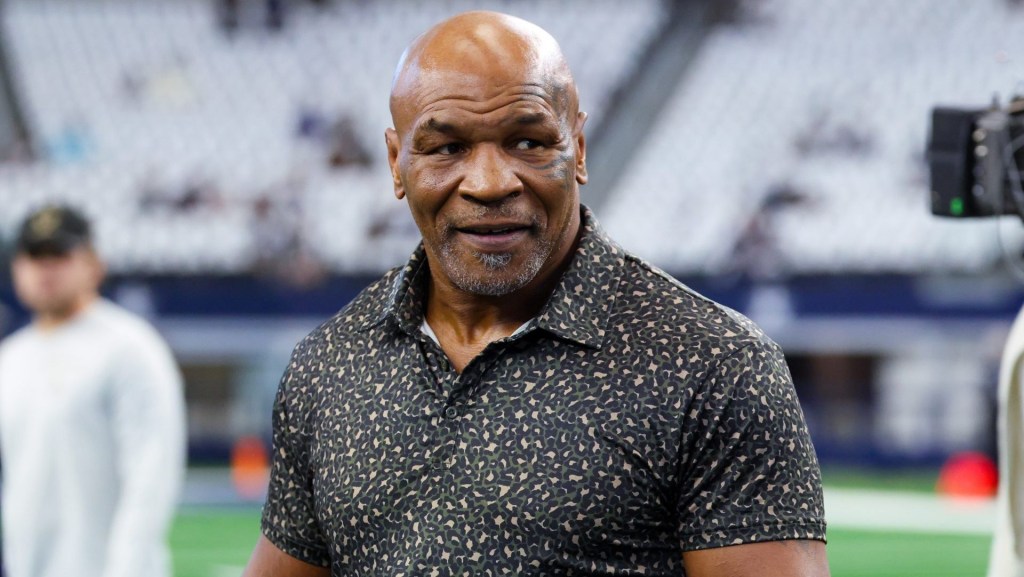

“I guess in some respects, did we create a monster?” asked Novitzky, who has been the UFC’s senior VP of athlete health and performance since 2015. “I guess, in some respects, maybe a little bit. But I think most people who hear or see Victor Conte realize who he is — and that’s a used car/snake oil salesman guy and bull—t artist.”

While laying out a few expletives of his own to FOS, Conte pointed to Federal Judge Susan Illston, who said Novitzky’s investigation had a “callous disregard” for the constitutional rights of MLB players when she quashed a subpoena of another lab Novitzky raided that was carrying out MLB’s drug testing.

“Victor is quite bright,” said Richard Young, one of the world’s leading anti-doping legal minds, who has worked alongside the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency since it was founded in 2000. “Victor was very generous with his time [during USADA’s investigations of track athletes who were clients of BALCO]. But every time you got into a conference with him, you kind of held your breath because you never knew what he was going to say.”

As far as for the syringes and vials Novitzky found in BALCO’s dumpsters, a scene reenacted in the documentary, Conte said they were all his anyway.

“I was doing testosterone and [the common anabolic steroid] Winstrol,” Conte said. “When you do Winstrol, you do it three times a week. You do testosterone time a week. So I was injecting myself four times a week. Well over 52 weeks times four, 200 of those wrappers were mine personally. It wasn’t athletes going there and injecting themselves — because nobody was but me.”

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jun 15, 2025; Seattle, Washington, USA; Botafogo owner John Textor inside the stadium before the match during a group stage match of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at Lumen Field.](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26465842_168416386_lowres-scaled.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)

![[Subscription Customers Only] Jul 13, 2025; East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA; Chelsea FC midfielder Cole Palmer (10) celebrates winning the final of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup at MetLife Stadium](https://frontofficesports.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/USATSI_26636703-scaled-e1770932227605.jpg?quality=100&w=1024)