LAS VEGAS — For one weekend, the Aria and Bellagio were taken over by college sports. And the main topic for the athletic directors, commissioners, industry heavyweights, private equity executives, and politicians present was the chaotic landscape of college sports.

Power conference administrators met with Bryan Seeley, the head of the new College Sports Commission that doesn’t have much enforcement power yet. During panels at the Sports Business Journal Intercollegiate Athletic Forum, administrators discussed the instability in college sports, from the inability to enforce rules around the transfer portal and eligibility and the coaching carousel. (The proximity of the National Football Foundation annual festivities brought together enough administrators to even discuss potential CFP expansion.)

The three potential solutions discussed included the SCORE Act, which would give the NCAA the authority to set rules; collective bargaining, the legal mechanism used by professional leagues to set rules without fear of antitrust litigation; and amending the Sports Broadcasting Act to pool FBS football media rights and, proponents of that idea say, therefore earn more money for everyone.

The one common thread among the various camps: They all said schools need more money.

“There’s a lot of whining and complaining,” Ohio State athletic director Ross Bjork said from the SBJ stage on Wednesday. “But we have to solve this.”

SCORE Act Problems

Since it was introduced this summer, the NCAA and power conferences have touted the SCORE Act as the solution to college sports’ woes. The legislation, a true wishlist for NCAA and power conferences, was the fruit of millions of dollars and six years spent on lobbying.

It would grant antitrust protections to allow the NCAA to set rules regarding eligibility and the transfer portal, and codify some of the rules the newly-formed CSC is set to oversee. It would pre-empt state NIL laws, and prevent athletes from becoming employees. This week in Vegas, multiple commissioners, from the American’s Tim Pernetti to the ACC’s Jim Phillips, along with multiple athletic directors, said legislation was necessary. (Phillips went so far as to say he would put it on his Christmas wishlist.)

There’s just one problem: It can’t seem to pass. Votes have been delayed now two times. And while one Congressional aide told Front Office Sports Republican leadership was hoping to bring the SCORE Act to a vote on the House floor this week, they are now aiming for next week—if ever.

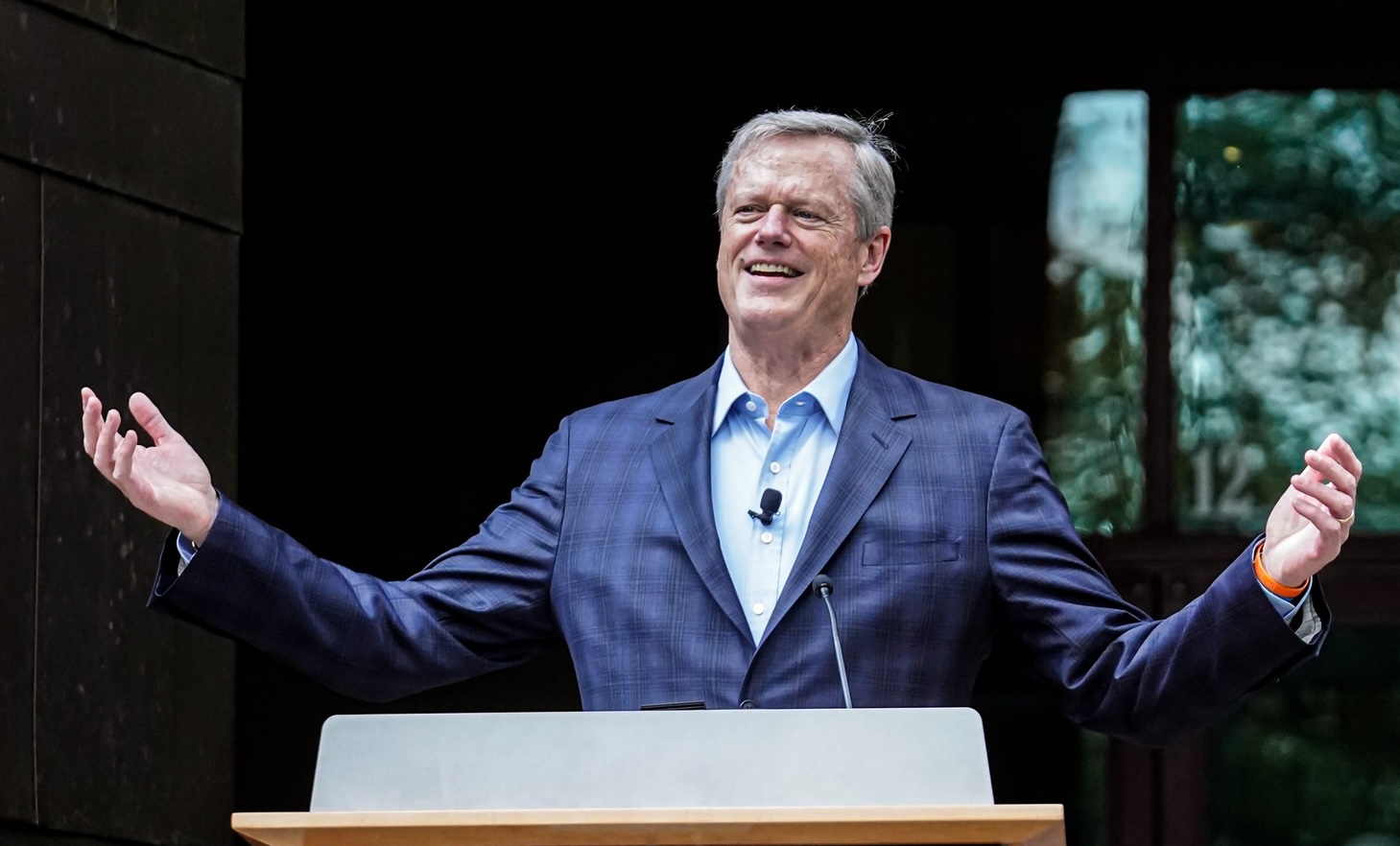

NCAA president Charlie Baker said he thought the SCORE Act was a victim of the bigger political picture in Washington. When asked whether he thought the window to pass it had closed, he said: “I don’t know. We’ll see.”

CBA Concept Gains Steam

In the absence of legislation, another idea has gotten more attention: collective bargaining.

On Monday, athlete advocacy organization Athletes.org (AO) released a proposal for a CBA among college athletes. In the pros, CBAs are negotiated between players’ unions and leagues to create enforceable restrictions around player movement, compensation, and other benefits. While players wouldn’t be employees—and therefore not receive the protection of employment laws—AO said it believes the CBA could function like any other contract.

The concept has been broadly endorsed by a growing number of athletic directors. Tennessee athletic director Danny White highlighted the chaos created by the unrestricted transfer portal and NIL. He said, as he has before, that collective bargaining could be a solution. “I think we need to get over our disdain for labels.”

SMU athletic director Damon Evans, who has previously not spoken on the topic, said: “I’m not against exploring collective bargaining. Right now there needs to be more protections for both sides.”

Even Baker, who leads the organization that has been against athlete employment and unionization for decades, conceded it was a concept worth exploring. “It’s the most detailed proposal I’ve seen on how you would actually think about doing this,” Baker told a small group of reporters, adding: “Bravo.”

He was concerned, however, that it may not offer as many guardrails as legislation would. And he highlighted a major question: “Would they do it at the conference level? Because schools are in very different positions.” He said he does not see it as a “one size fits all” solution.

Sports Broadcasting Act Amendment

Some particularly powerful individuals—most notably Texas Tech booster and university board chairman Cody Campbell—have proposed amending the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961. The SBA, as it is known, offers professional teams the ability to pool their media rights to sell as one league package without the fear of antitrust challenges. Proponents of amending the SBA, like Campbell, say that selling all FBS football media rights together could increase the overall value than the current fractured deals, generating more money for the entire ecosystem.

Pernetti spoke favorably about amending the SBA—a concept that is now in multiple pieces of legislation competing with the SCORE Act. “College sports is leaving money on the table in media rights,” he said Tuesday.

But Baker said he wasn’t so sure that pooling media rights would generate more money after all. “It’s the schedule that really drives [value],” Baker said. “So the question is, if you pooled all the rights, what would you do with respect to who plays who and when? Because I don’t think the conferences would be willing to give up their own schedules.”

Of all the ideas swirling in the air along with the smell of tobacco, none appeared to have garnered a complete consensus. But there was a sense of camaraderie growing to stop the infighting and focus on these industry-wide issues. Baker praised Campbell for his transparency, despite Campbell lobbying against his bill this past fall; Campbell said he did not want relationships to be adversarial. Big 12 commissioner Brett Yormark came to the defense of ACC commissioner Jim Phillips. Athletic directors praised Bryan Seeley and the CSC despite previously reported issues with its functions.

It’s time, Pernetti said, to “stop tearing each other apart.”