Every August in Williamsport, Penn., the Little League World Series brings 20 teams from across the world to compete in one of the most iconic youth sporting events. On the field, players ages 10 to 12 vie for a world championship. But off it, an entirely different game unfolds: pin trading.

Within the Little League International Complex, players, fans, and coaches swap what is arguably Little League’s most valuable currency. The pins—small, wearable designs representing players, teams, towns, or events—have become a fixture of the global event.

Pins are produced by teams, players, coaches, and the Little League itself. They’re distributed at the LLWS in a free-for-all style, where collectors gather to trade with one another, often right in the complex or in makeshift trading areas. To be considered an official Little League pin, each must display its state initials and district number, such as NY-18 for the 18th district of New York. Pins can either be sold or traded at the LLWS, and the rarest ones can command huge returns in trade.

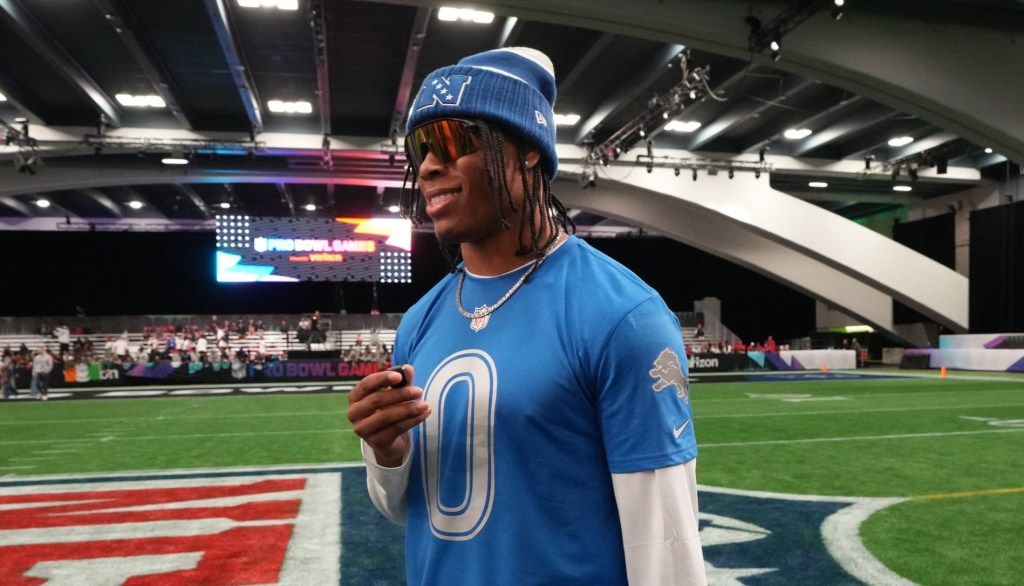

“It’s pretty addicting,” says Jeff Frazier, a former Detroit Tiger who won the 1998 Little League World Series championship with Toms River, N.J. “I got here when I was 12, and here I am 43 and I got the same damn feeling.”

According to the league, the pin-trading phenomenon at the LLWS started in the mid-1970s when a team from Taiwan brought their own custom pins to Williamsport to trade. Then, Little League International began producing its own pins in 1983: a small, simple design of a hot-air balloon that is among the rarest in circulation today.

Over time, the designs have become more elaborate. Some feature schools, towns, or local landmarks, while others depict mascots, MLB players, or commemorations of major historical events. All pins that use the Little League name or logo must be licensed through the league’s website.

Pin trading has since evolved into a year-round activity. Winter conventions bring collectors together in the offseason; and in August, the hunt shifts to Williamsport, where pins past and present can be found from sponsors, tournaments, and even makeshift trading halls set up in local hotels. While most exchanges are straight barter, there’s also a secondary market on eBay and other platforms, where pins can sell for anywhere from a few dollars to several hundred.

Like any collectible, the rarer, the better. Some pins, such as those commemorating major historical events, become valuable almost instantly. Frazier recalls collectors going “crazy” for designs featuring the World Trade Center after Sept. 11.

Designs tied to baseball milestones are just as coveted. Last year, Aaron Judge’s home-run record Little League pin became one of the rarest in the trading circuit, Frazier tells Front Office Sports.

Production runs for most pins at the LLWS can be in the thousands, making scarce pins in the hundreds or fewer especially sought after.

This year, one specific pin generated buzz before the World Series even began.

The “Batflip 2025” pin commemorates the moment 12-year-old Marco Rocco was ejected and suspended for a game after flipping his bat following a home run for his Haddonfield, N.J., team. His family successfully challenged the suspension in court, drawing reactions from MLB players, media, and fans across the country.

The design shows Rocco mid-celebration, with “Batflip 2025” at the bottom and “Haddonfield” inscribed along the side, as well as the “NJ-13” district code to mark its origin. There are only 75 of these pins, which also mark Haddonfield Little League’s 75th anniversary. They are available only through trades in Williamsport; none are for sale. The Rocco and Frazier families jointly handled the design, details, and production of the pin.

“That’s why this pin is going to be in higher demand,” Frazier tells FOS. “It’s an event that happened that would probably never happen again in Little League.”

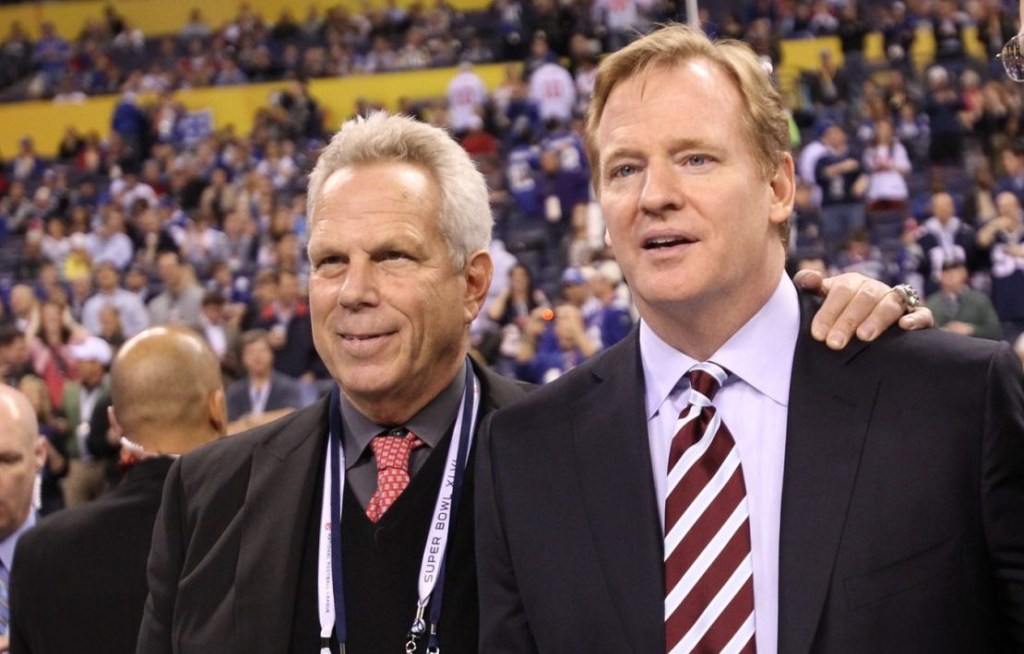

Ken Goldin, founder of Goldin Auctions and star of Netflix show King of Collectibles: The Goldin Touch, sees the “Batflip 2025” pin as a prime example of the frenzy for rare pins. While there aren’t thousands of people who want it, he says, it will be a coveted piece within the Haddonfield and Little League community writ large.

The long-term value of Rocco’s pin could skyrocket if his baseball career takes off. “The number-one factor that will determine value 10 or 15 years from now,” Goldin says, “is if Marco Rocco becomes a professional baseball player. If he does, this is legitimately the first collectible he was ever part of.”