The NFL and ESPN are touting their blockbuster pact as a win for fans, but the road to closing could be bumpy, as evidenced by the fact that the league has reportedly already begun a lobbying blitz on Capitol Hill.

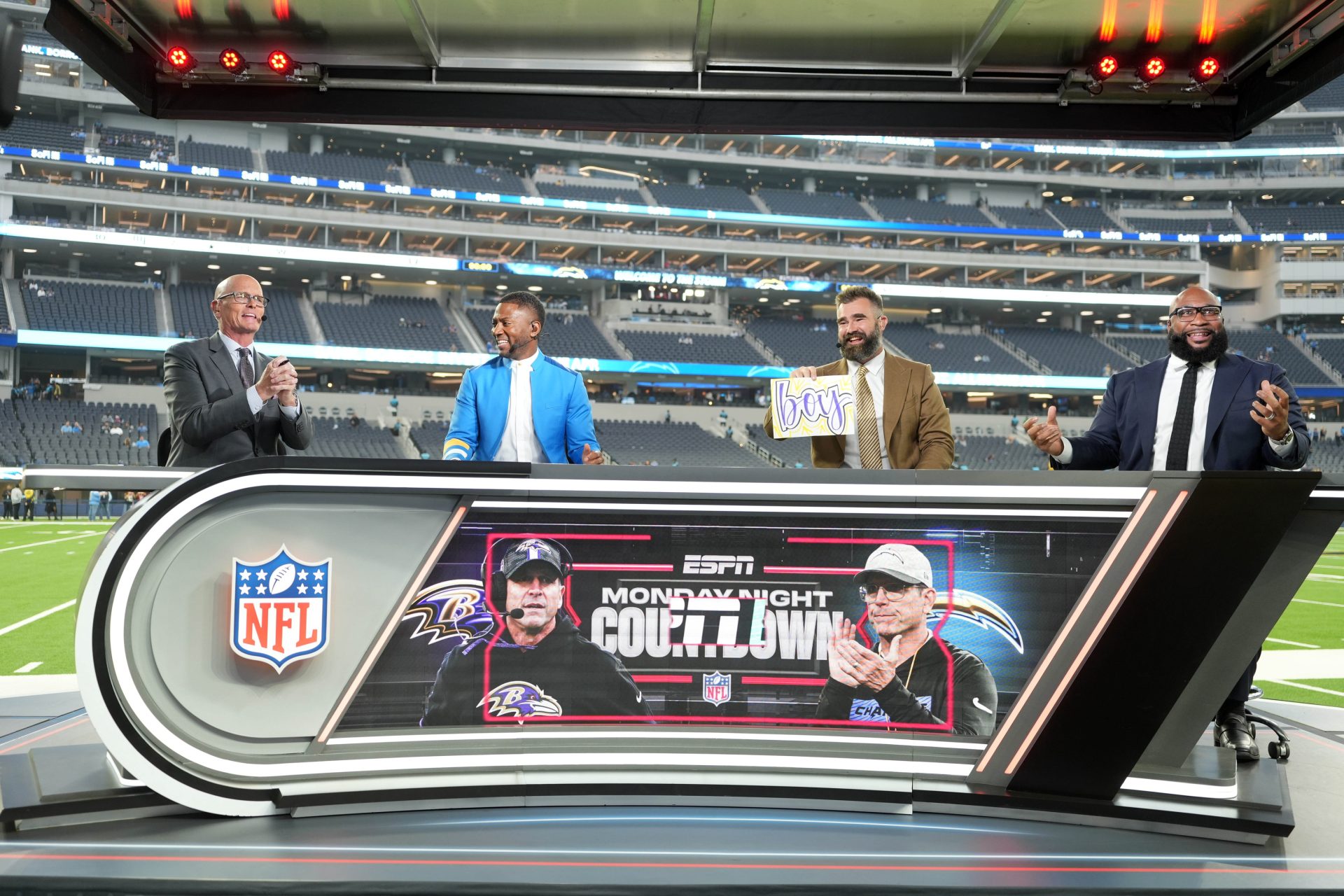

The “non-binding” agreement sees the league taking a 10% equity stake in the broadcaster, with ESPN picking up NFL Network and the rights to distribute RedZone to pay-TV operators. The stake is valued at between $2 billion and $3 billion, according to The Wall Street Journal. If approved, the NFL would continue to own RedZone and retain digital rights. It represents the latest in a string of transactions in which media partners are taking equity stakes in the leagues they televise and cover.

The fact that it’s “non-binding” means the two sides still have to negotiate definitive terms, but experts say its announcement at this point is not unusual. Looming larger are the questions of whether President Donald Trump will wade into the situation and whether regulators will decide the deal has potential anticompetitive or anti-consumer effects.

The league has already reached out to 30 congressional offices to talk about how the deal will “result in greater consumer choice,” Reuters reported—indicating that, internally, the NFL understands there are potential roadblocks, even as it champions the agreement in public as one that will benefit fans and make it easier for consumers to watch football. Among the supposed benefits to consumers that ESPN and the NFL are touting is the potential for additional RedZones, including in college football, as well as the NBA and NHL.

At least one lawmaker isn’t buying what the NFL and ESPN are selling.

“If history tells us anything, billionaires in boardrooms are going to gouge hard-working Americans without thinking for a second of the impact on the fans,” Rep. Pat Ryan (D., N.Y.) told Front Office Sports. “I’m particularly concerned by any deal that would make games exclusive or unavailable for folks who can currently watch on cable.” In the aftermath of the ESPN deal, the league is reclaiming four NFL Network games and looking to possibly sell them in a package to streaming services, Bloomberg reported last week.

Ryan pointed to Amazon’s exclusive Thursday Night Football package and 2024’s Peacock-only NFL playoff game as proof fans could lose out. “It’s time for Congress to re-examine sports leagues’ antitrust exemption and put power back where it belongs: with the fans,” he said.

Steve Ross, professor of law at Penn State, tells FOS that while he certainly sees how the deal will benefit the NFL and ESPN, he’s not so sure consumers will come out ahead.

“I see this as a long-term deal by a bunch of rich people to get richer,” he says. “I see how they might make more money, but it’s not clear if the NFL is going to be marketed more effectively because ESPN and the NFL are now partners somehow.”

The Trump Piece

It’s unclear whether the opinions of Ryan and Ross are shared by the dozens of lawmakers the NFL has reportedly been talking to since the deal was announced. Another question is whether Trump will enter the fray, and what side of the matter he might fall on.

It’s impossible to know what Trump might do “because he’s so unpredictable,” Irwin Kishner, co-chair of the sports law group at Herrick Feinstein LLP, tells FOS.

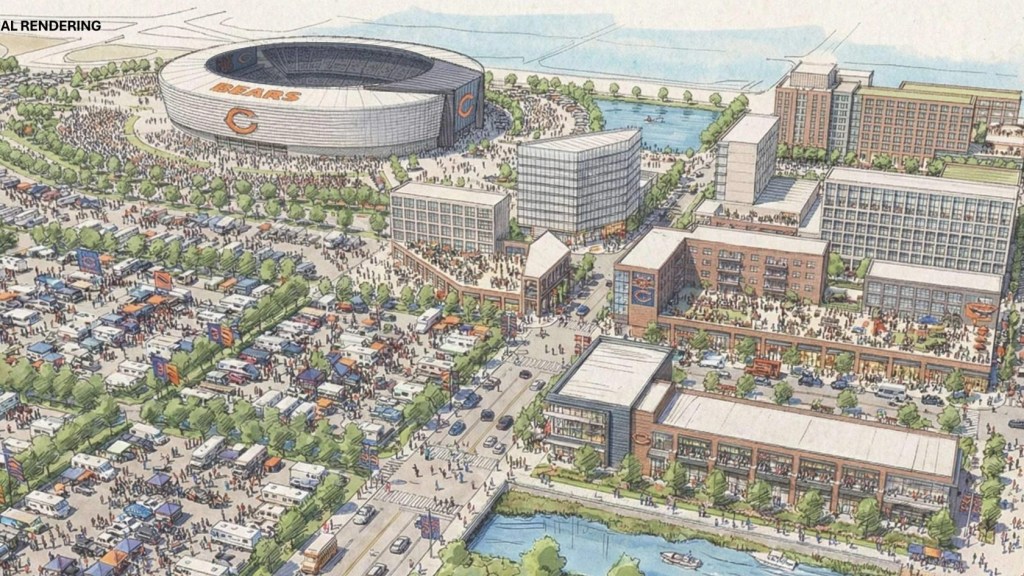

“Is he going to get in the middle of this the way he recently did with the Commanders stadium deal?” Kishner says. “Who knows?” There, Trump last month threatened to kill a $3.8 billion stadium deal between the Commanders and District of Columbia leaders should the Commanders not revert to their prior name.

Ari Fleischer, the former White House press secretary to President George W. Bush, told FOS that the proposed deal is “political catnip” for Trump, who has a long history of failing to buy NFL teams and has been at odds with the league over politics and new kickoff rules.

Legal Hurdles Ahead

Trump’s personal whims notwithstanding, the agreement will almost certainly trigger review under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, which requires companies to notify the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice before completing certain large transactions. The HSR process gives regulators a chance to determine whether a deal may substantially lessen competition, and to block it if necessary.

“I suspect it is required,” says Kishner. “The question I would have [as another broadcaster] is how does this affect my business? Am I getting left behind? What do I do to counteract or compete against this?”

Reuters reported the DOJ is expected to perform a “substantive review” of the deal, and that it could take up to a year for the deal to obtain U.S. antitrust approval.

Disney and ESPN (which is owned by Disney) already know a thing or two about the difficulty in completing deals due to potential antitrust issues. Earlier this year, Venu Sports, a planned streaming joint venture between Disney, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery, was shuttered amid controversy.

Fubo had sued over the formation of Venu last summer, arguing it violated U.S. antitrust law. Fubo succeeded in blocking the intended debut of Venu last fall, and the case was still ongoing when the saga came to a sudden end in early January, with Disney agreeing to buy a majority stake in Fubo and the parties dropping the lawsuit.

The Disney-Fubo deal is still working its way through the system, and it too has faced pushback, including from satellite TV carriers DirecTV and EchoStar, which filed letters with the U.S. District Court arguing that Disney simply paid Fubo “to ensure cooperation from an aggrieved competitor.”

“The federal government has a coterie of things to protect the airwaves and so forth,” Kishner says. “If the government is against it, it’s going to make life harder [for the NFL and ESPN].”

Ross sees potential parallels to past antitrust battles. In the 1950s, the federal government forced DuPont to sell its 23% stake in General Motors over concerns it would distort purchasing decisions. Perhaps more pertinent is a case in another country. In the 1990s, the U.K. government blocked the proposed acquisition of Manchester United by Sky Sports.

Ross says that deal failed on “two grounds”: First, the U.K. Monopolies and Mergers Commission was “concerned that if Sky executives were at the [English Premier League] table, this would distort the EPL’s decision-making concerning to whom they would license their games.”

Second, the regulator was worried it would be unfair if a team was owned by someone more focused on making money from media rights than winning games.

Ross says to consider the following: What happens if another league is being launched and wants to reach a commercial agreement with ESPN, but success of the league could be adverse to the NFL. “How does ESPN respond?” Ross says. Same goes for a vice versa situation—if there’s some deal that ESPN wants to do that might not benefit the NFL.

“I don’t see what’s on the plus side for the consumer,” Ross tells FOS. “The NFL is such a gorilla, and these deals allow a lot of discretion in how you negotiate. That creates room for distorted incentives and informal pressure.”

—Dennis Young contributed reporting.