As ace ESPN NFL reporter Seth Wickersham reflects on how much power modern-day quarterbacks have amassed in their organizations, he recalls the time Jets coach Lou Holtz wanted to get in touch with Joe Namath.

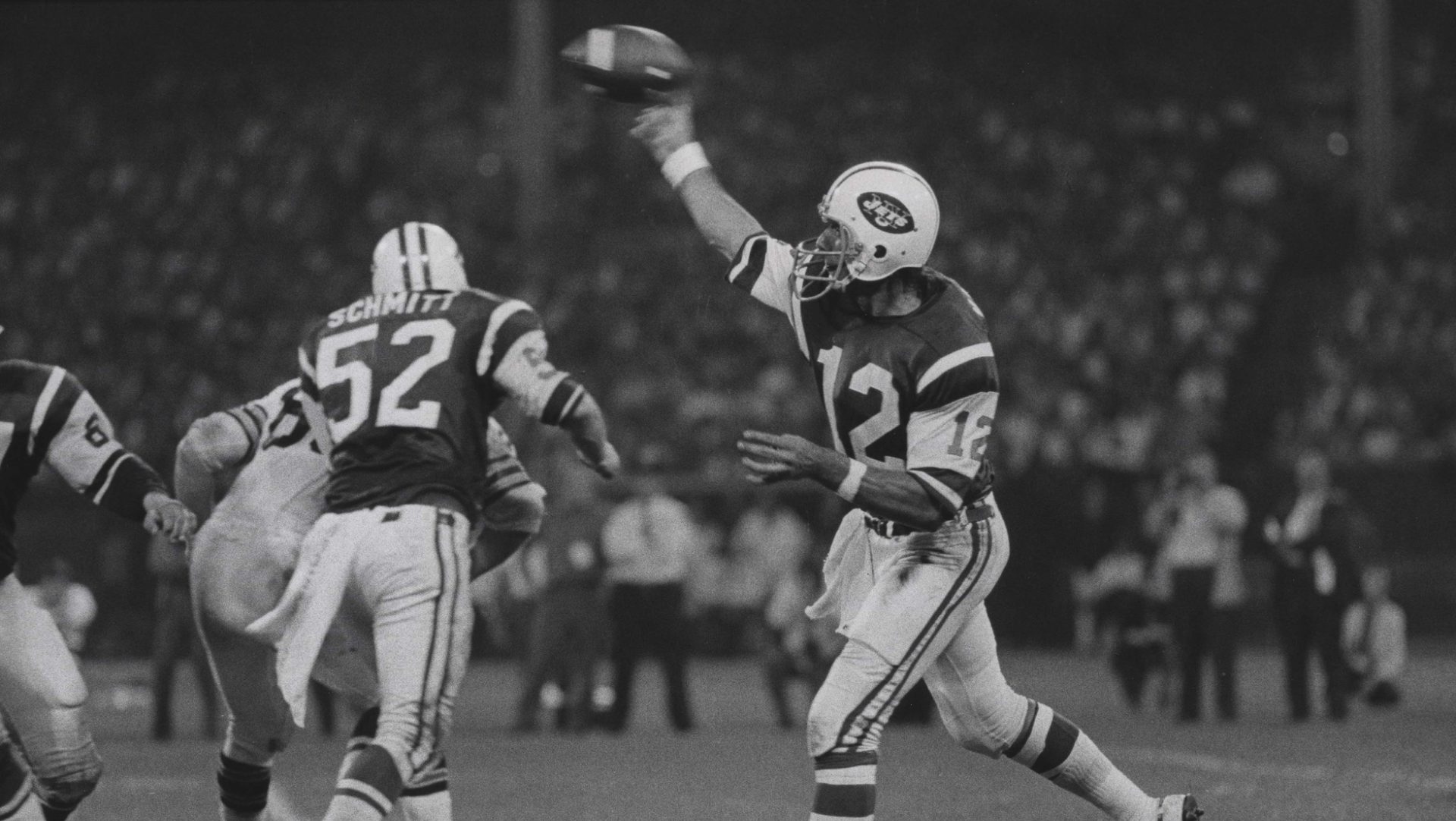

In 1976, Holtz was named head coach of the Jets, but nobody with the team could give him Namath’s phone number. Holtz eventually reached Namath’s agent, Jimmy Walsh, but his request for the quarterback’s number was rebuffed. “The agent basically said to him, ‘I’ll take the number, and if Joe wants to talk he’ll call you,’” Wickersham says.

When modern-day football fans see how much decision-making power Peyton Manning wielded in Indianapolis and Tom Brady in Tampa Bay (after leaving New England in part to attain more control), it’s natural to think it was unprecedented. However, in an interview with Front Office Sports Wickersham, whose book American Kings: A Biography of the Quarterback comes out Sept. 9, muses, “Time is a flat circle.”

Wickersham recounts how through the decades, quarterbacks like Namath, Johnny Unitas, and John Elway exercised significant power within their organizations, arguably superseding the authority of head coaches and GMs as second in command to the owner.

Many star quarterbacks must navigate a dichotomy where they are essentially part of the managerial class, while leading a locker room of men who are ostensibly their peers.

“Unitas talked about how his teammates didn’t really look at him like he was one of them until he told the coach to fuck off,” Wickersham says. “Y.A. Tittle found the same thing. Steve Young, decades later, too.”

Throughout the years, it’s been a pendulum as the power has swung between quarterbacks and coaches.

“When Paul Brown began his rise, it really started the power movement away from the quarterback and towards the coach,” Wickersham says.

While Wickersham points out that no quarterback has ever amassed as much power as Michael Jordan did during his second three-peat with the Bulls, there are some who have gotten close. Elway was offered an ownership stake in the Broncos late in his career by the late Pat Bowlen (this would no longer be allowed), but he turned it down. “I bet you anything that he wishes that he kept it,” Wickersham says.

“There’s a lot of evidence that Peyton Manning was the most powerful person with the Colts for most of his tenure there—besides Jim Irsay,” Wickersham says.

On the flip side, Manning’s longtime rival Brady had to leave New England for Tampa Bay to gain true organizational juice.

“Brady wanted to get involved with scouting and personnel, and after the number of years he’d spent in the NFL and the success that he’s had and number of players he’d seen, I think you could make a case that he deserved to be in that room. But, that was something that [Bill] Belichick would never let him do,” Wickersham says. “You understand the reason why from the coach’s point of view, too—you can’t have players thinking that they’re going to get cut unless they’re nice to the quarterback.”

Wickersham notes that Brady wasn’t entirely “calling the shots” in Tampa, but it was clear that GM Jason Licht valued his input. The team acquired Antonio Brown and Rob Gronkowski, and a coaching change from Bruce Arians to Todd Bowles was made perhaps to coax Brady out of retirement.

As far as Manning seeming to effectively be the Colts’ offensive coordinator, Wickersham recalls the cyclical nature of this on-field power. Namath called the plays in Super Bowl III. “Johnny Unitas took the responsibility of calling plays to the bottom of his soul,” Wickersham says. “It was a huge point of pride for him. When Don Shula stripped him of play-calling responsibility, kind of in the Paul Brown mold, that was a huge emasculation for him.”

Brady and Manning had different levels of control within their teams, which was reflected in how differently they had to plan for games.

“For as hard as Brady worked, I think his preparation for games was quite a bit different than Manning’s because the coaches would game-plan and then bring him into it,” Wickersham says. “What he needed to study was a lot less than what Manning needed to study for a lot of their careers.”

The biggest star quarterbacks of today, including Patrick Mahomes and Josh Allen, by all appearances haven’t sought to attain outsized levels of power. Mahomes, for his part, plays in a quarterback-friendly system. As with Brady in New England, he’s playing on a contract substantially below his market value.

While no one is playing a sad violin for Mahomes making $45 million to $50 million a year, Dak Prescott reset the market at $60 million annually in a blockbuster contract last offseason. How much could Mahomes make on the open market if he were a free agent and truly sought to maximize his earnings?

“I think if his contract ended after the Super Bowl against the Eagles, I would guess he’d make $70 [million] to $80 million a year,” says Wickersham.