The second iteration of the North American Soccer League was a lower-tier league that existed for only a handful of seasons, and it went defunct more than seven years ago. But a lawsuit the league filed attracted dozens of lawyers and an overflow courtroom in Brooklyn federal court Monday. That first day went more than six hours for opening arguments, and promised testimony from NBA royalty.

That’s because NASL’s antitrust trial against the U.S. Soccer Federation and Major League Soccer threatens to rip the veil off the cozy world of American professional soccer, with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake.

NASL’s outside counsel, Jeff Kessler, is a titan of American sports law. He ripped into the dominant soccer organizations in his two-hour, 15-minute opening argument.

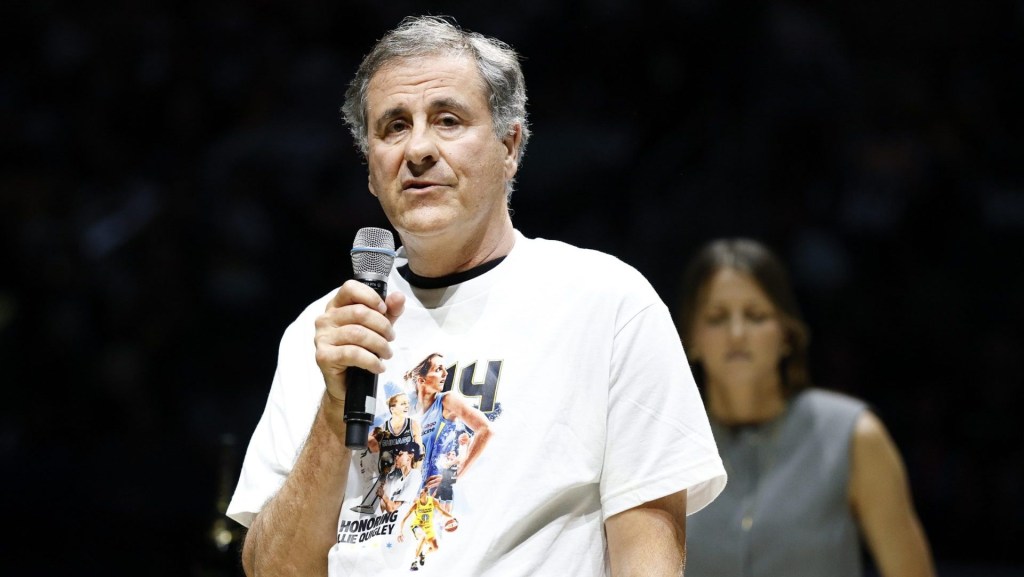

“It’s a small, insular world,” Kessler told the jury. “Either you belong or you don’t.” Of NASL chairman Rocco Commisso: “He wasn’t part of their club.”

NASL alleges MLS and USSF conspired to bar NASL from competing with MLS, and then further unjustly deprived the upstart league of renewing its Division II status—the second-highest level in the U.S. soccer pyramid—forcing its dissolution in 2018. MLS and USSF deny the two entities conspired, and contend NASL’s woes were caused by a major investor who was ensnared in the 2015 FIFA bribery scandal.

“Traffic was bailing out the league again and again and that came to an end,” USSF outside counsel Chris Yates told the jury, referring to NASL investor Traffic Sports. “The Traffic Sports crisis put the league into a downward spiral.”

The three-week trial, presuming there is not a settlement, will see the testimony of MLS commissioner Don Garber, FC Dallas and Kansas City Chiefs owner Clark Hunt, Big East commissioner Val Ackerman (she was a USSF board member during the period in question), and soon-to-be NBA Hall of Famer Carmelo Anthony, who owned the NASL Puerto Rican franchise.

Kessler described longtime soccer executive Sunil Gulati and Garber as “two peas in a pod.” Gulati had simultaneous roles with MLS and U.S. Soccer, and Kessler said he would call Gulati and Garber as witnesses to the allegedly illegal conspiracy between MLS and USSF. Lawyers for USSF and MLS strenuously argued there is and was nothing untoward about the MLS-USSF relationship, and Garber recused himself over the critical votes in question.

Those votes were by U.S. Soccer in 2015 to deny NASL’s bid for a Division I sanction on par with MLS, and in 2017 a denial of a renewal of its Division II sanction. At the heart of the dispute is whether the USSF used its power as the sport’s governing body in this country—giving it the right to sanction leagues—to protect MLS from NASL’s competition.

NASL is suing for up to $170 million. The damages, if awarded, would be tripled under antitrust law.

Brad Ruskin, MLS’s outside counsel, told the jury it is “absurd” and “fictional” to argue MLS saw NASL as a competitive threat, listing the billions of dollars invested in MLS compared to the millions of dollars put into NASL.

“NASL was never a competitive threat,” he said. “NASL was just not on MLS’s mind.”

The coming weeks could get rancorous. Ruskin pointed out Anthony paid nothing for his team and only agreed to promote it. And he said the trial would reveal that Commisso, the colorful former NASL chairman who is funding the lawsuit, had a fake Twitter handle in 2017 he used to post nasty messages about the defendants.

Yates contemptuously referred to Kessler as having a “made for litigation argument,” warning the jury “he is trying to mislead you,” for using “smoke and mirrors” and “playing tricks.” Kessler and Yates are also currently on opposite sides of the lawsuit brought by Michael Jordan over the NASCAR charter system; Kessler is also the lead attorney for the plaintiffs in the landmark House v. NCAA case.

Kessler offered as proof of unfair treatment that USSF granted waivers to MLS over the years allowing it not to meet stadium capacity thresholds and other standards necessary to secure a Division I sanction, while denying them to NASL in its 2015 bid.

But Ruskin argued when USSF agreed to a sanction and allowed standards waivers, there were reasons for this: a team, for example, moving into a smaller facility while building a new one. When NASL was turned away for waivers, he said, it was over poor business plans.

“NASL never met U.S. Soccer’s minimum standards,” Yates said. “It just never put in the work, never built those stadiums, never went out and signed great players.”