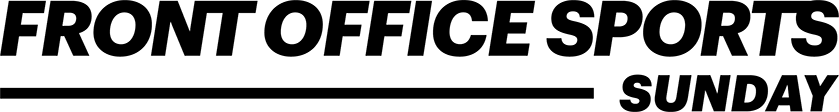

For a short time, some schools and betting operators found themselves in happy marriages.

Four years ago, as athletic departments scrambled for alternate revenue streams amid the COVID-19 pandemic, gambling provided a perfectly timed solution. The activity was becoming legal in states across the U.S. Fans were starting to bet on NCAA events with abandon, and betting operators clamored to become the go-to sportsbook for college sports. Athletic departments—many once morally opposed to anything related to wagering—jumped at the opportunity to strike sponsorship deals with sports betting operators. The feeling was mutual.

Now, athletic departments are again searching for more money: Thanks to a recent settlement in the House v. NCAA case, power conference athletic departments will likely have to cough up around $20 million each per year to pay their players. But this time, they won’t be turning to sports gambling to fill the gap. Their relationships have soured due to backlash, new industry regulations, and changed strategic goals for betting operators. These types of deals are no longer an option.

Until 2020, there were only two known partnerships between university athletic departments and sports betting operators: British company William Hill secured deals with UNLV in ’17 and the University of Nevada-Reno in ’18.

But two years later, the University of Colorado-Boulder became the first school outside Nevada to ink a sponsorship deal: a seven-figure partnership with Australia-based PointsBet. Although hardly a feeding frenzy, several high-profile schools followed Colorado’s lead between 2020 and ’23: Among them, Michigan State signed a deal with Caesars Sportsbook.

LSU, too, secured a partnership with Caesars in 2021. Like the Boulder-PointsBet deal, it was worth around seven figures. “LSU has always taken pride in providing fans with unique, innovative, and world-class experiences, and our new partnership with Caesars Entertainment will do just that,” LSU athletic director Scott Woodward said in ’21. “We share a clear vision of how athletics and entertainment can come together to enhance the fan experience, and we are excited to join with Caesars to make that vision a reality.”

Even then, the deals were largely controversial because they allowed schools to profit from promoting an activity that was still illegal for their majority under-21 student population—as well as their athletes. LSU, for example, reportedly sent out email advertisements to its student body promoting sports gambling—emails that also went to underage students. Boulder earned a $30 commission from every sign-up PointsBet received from the university community. Michigan State and LSU faced backlash from faculty for their deals with Caesars, notes UNLV sport management professor David Vinturella, who worked in marketing and sponsorships for Caesars in 2022.

In public announcements, universities attempted to assuage detractors with the promise that all their partnerships included some form of responsible gambling education. The Buffaloes tried to silence the criticism by watering down their partnership in January 2023, when they announced they would no longer receive commission from PointsBet sign-ups. “After review and discussion with our partners at PointsBet, it was determined that the referral program was not providing the ancillary benefits to our campus that were anticipated when the agreement was made in 2020, so we made the mutual decision to discontinue that portion of the agreement,” the school told Front Office Sports at the time.

But it wasn’t enough. In 2023, schools and sports betting operators began to divorce.

In response to the backlash, in March 2023, the American Gaming Association announced that its members, which include sports betting operators, were prohibited from sponsorship deals with NCAA athletic departments altogether. (The AGA also placed a ban on operators offering name, image, and likeness deals to college athletes.) Not only were new partnerships off the table, but the AGA said all members who currently had deals with schools had to terminate them by July 1.

The new policy was the result of multiple rounds of AGA committee engagement, AGA’s SVP of strategic communications, Joe Maloney, tells FOS. He described the decision as “noncontroversial” among AGA members, suggesting that sports betting operators appeared to come to a consensus that the advertising benefits weren’t necessarily worth the public controversy.

“You go to market and you begin to determine what are the partnerships from an advertising and marketing that make sense, pursuant to industry profitability, but also industry brand health and reputation,” Maloney says. “We observed partnerships happening and the response to those, and it became clear over time that from an AGA membership standpoint, it made sense to move forward with these changes.”

The AGA has jurisdiction over only the companies it counts in its membership—including most, but not all, sports betting operators—but the legislation helped put an industry shift in motion that killed all the Division I deals. And even Caesars, while not bound to AGA membership standards, ended its partnerships with Michigan State and LSU in late May 2023. A spokesperson for Caesars did not respond to an emailed request for comment from FOS.

Last month, power conferences agreed to a settlement in House v. NCAA that will require them to begin revenue-sharing with players for the first time in NCAA sports history. Each school will pay an annual sum of around $20 million, starting potentially as early as 2025.

Dozens of athletic departments rake in more than nine figures per year, but they’re talking like it’s 2020 again: back in a frantic search for more revenue streams. They’ve pursued many avenues for revenue, including using sponsorship logos on fields, allowing jersey patches, inking private equity deals, and even selling naming rights to conferences. But gambling partnerships are still off the table—and it’s not just because of the AGA’s regulations.

State regulators have complicated any future deals, too, Vinturella notes. In Ohio, for example, gambling operators can’t advertise within a certain radius of a school. General restrictions for betting on college sports also make the deals less palatable for betting operators. Several states have passed legislation prohibiting bets on college teams before they reach championship tournaments (when NCAA president Charlie Baker was the governor of Massachusetts, he implemented this law in his state). Others have banned prop bets on college athletes—another issue Baker has championed. In 2023, Louisiana even passed a state law banning any “postsecondary education institution” from “promotional agreements” with sports betting companies.

And then there’s the return on investment. Both Vinturella and AGA’s Maloney say that sports betting operators don’t want to deal with the criticism that was aimed at the deals from 2020 to ’22. Vinturella also suggests that changing business models for sports betting operators has pushed them away from these types of sponsorship deals, even if a school approaches them. “I think sports betting operators are getting leery of the value they’re getting in return,” he says.

So, even while betting on college sports grows only more popular—and while schools and governing bodies alike search for money wherever they can find it—the union between the college sports world and betting operators won’t likely be rekindled.

There is an alternative for the future, Vinturella says. Schools can partner with resorts and hotels that have casinos or sportsbooks on their properties. The advertisements themselves don’t promote gambling, but they provide an indirect avenue for schools to profit from the money in the gambling industry, and for sportsbooks to win over new customers. On the value of these deals, Vinturella says: “Extremely lucrative.”