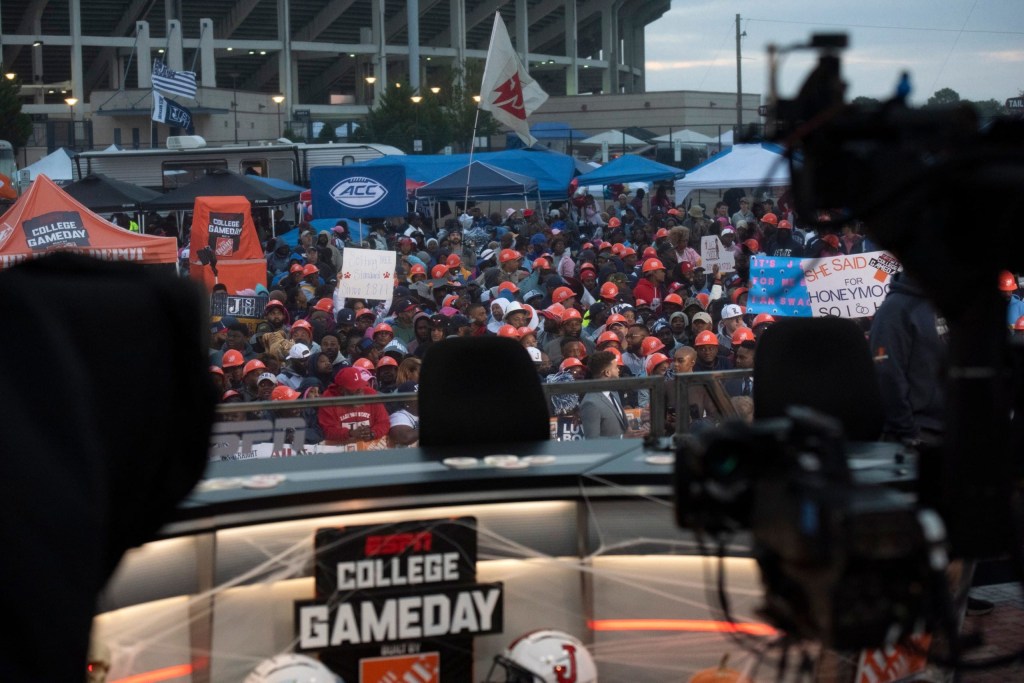

Since ESPN’s weekly pregame show “College GameDay” launched in 1993, it’s become part of the fabric of U.S. sports culture.

Each week, the show travels to a different school, bringing more than 100 members of a production crew, star anchors and analysts, and a full-on set. It showcases storylines and games across the sport’s landscape — and multiple college sports administrators told Front Office Sports they consider it a “three-hour infomercial” for the host school.

The vast majority of GameDay’s stops are for top Power 5 matchups. Ohio State and Alabama, for example, have each hosted more than 15 times.

But this year, it has embraced new locations and non-Power 5 programs — by Week 11 it will have visited three schools for the first time: Kansas, App State, and Jackson State.

There’s a symbiotic relationship between ESPN and host schools: The show has provided major marketing value for the school and surrounding community, as well as an immediate economic boost.

In turn, ESPN has enjoyed a tangible increase in ratings, and employees have been welcomed with unparalleled enthusiasm, GameDay’s coordinating producer Drew Gallagher told FOS.

Putting On The Show

With the exception of a few annual matchups — like Army-Navy — ESPN’s producers choose their next GameDay location just one week in advance.

The show had planned to head to Texas A&M in Week 3 but ended up at App State — partially because the Mountaineers had upset the Aggies the week before.

“We don’t have any sort of checklist,” Gallagher said. “When a team becomes a story, that’s what gets on our radar.”

Once a location is chosen, athletic department officials embark on a whirlwind week of meetings and coordination. In many cases, both academic and local officials join in.

“Especially for a place that’s hosting it for the first time, it’s a complete university effort,” App State Senior Associate AD for Strategic Communications, Joey Jones, told FOS.

- The GameDay crew provides schools with an extensive checklist including some of the most minute details, such as how much power the set will require. Particularly for a first-time host, the placement of the set is a major decision.

- There are school-specific tasks as well. “Sometimes we’re asking them to do things like move light posts or shut down major roadways,” Gallagher said. “It can be a disruption to the school and to the campus.”

- An example: GameDay’s arrival at Kansas fell during the school’s fall break, when much of the student body leaves, Kansas Deputy AD for External Affairs and Revenue Generation Jason Booker told FOS. So the school worked with Greek life to keep fraternity houses open for the weekend.

For the schools, the disruption is more than welcome. “It’s just nonstop planning for the entire week to get ready for what is a signature moment in our university’s history,” Jones said.

The GameDay bus arrives on Thursday, and the set-up begins.

‘A Three-Hour Infomercial’

The GameDay crew “doesn’t view it as our job to provide propaganda for the school,” Gallagher said. But from the featured content to the physical backdrop, “it’s only natural that the show is just going to end up putting a spotlight on the school in a positive way.”

“Having College GameDay and all that surrounds it was really immeasurable for us,” Jones said. But there are a few quantifiable categories.

First, the athletic department earns nationwide prestige.

Kansas, universally known as a basketball school, hardly gets any exposure for its football program. As an HBCU, Jackson State gets far less coverage than FBS schools despite its recent success — GameDay unquestionably provided its biggest spotlight.

The free marketing, in fact, starts days before the GameDay crew even shows up, school officials said. In the week leading up to the show, the host team gets multiple spots on “SportsCenter” and extra coverage from local media outlets.

That marketing can translate directly into revenue. Jones noted that App State donors who may not have “paid much attention” in recent years demonstrated a renewed sense of interest.

The school’s academics get free advertising, too. GameDay plays into what’s known as “The Flutie Effect” — how a dominant athletic program can translate to an increase in applications.

Kansas had already seen a 30% uptick in applications since its basketball team won the national championship, Booker said. So he expects that the football team’s success — and its exposure on GameDay — will only add to that momentum. “Those are all intangible things that students are looking for,” he said.

Beyond campus borders, local communities see an immediate positive economic impact.

- The 100-plus-person GameDay production crew fills hotels and restaurants.

- Fans from surrounding regions, opposing teams, and even the show itself pour into these towns.

- The show spotlights regional businesses, like restaurants, as the hosts enjoy televised tastings of local fare.

What can that add up to? Jackson State estimated that GameDay was part of a weekend that generated $8.9 million for Jackson, Mississippi.

Perhaps that’s why the show has caught the attention of lawmakers. This week, state senator Ellie Boldman drafted a bill to bring the show to Montana.

“The amount of money the free exposure provides for the universities featured on its program is enormous, coupled with the economic benefit for the private sector, including our hotels, restaurants, bars and related sales of game day gear,” she told 406 Sports. “It’s time for the State of Montana to be in that spotlight.”

A Win-Win For ESPN

Some might wonder whether GameDay has taken a strategic risk by visiting multiple schools without the brand recognition of its usual Power 5 hosts. But the numbers say otherwise.

Through Week 9, GameDay has seen its best ratings start since 2009, according to the network.

- In Week 3, App State drew 2.2 million viewers on average, with 2.8 million in the show’s final hour. That was a 15% increase from the Week 3 matchup in 2021.

- In Week 6, Kansas notched 2.3 million viewers on average, and 3 million during the last hour — 22% more than in Week 6 of 2021.

- Last week’s show at Jackson State, despite being an FCS school, wasn’t far behind. It drew 1.8 million viewers, with 2.3 million in its final hour.

For ESPN production employees, the constant travel and weekend hours can be grueling. But particularly at first-time host schools, the crew receives a hero’s welcome.

“They tend to roll out the red carpet,” Gallagher said.

App State’s chancellor, for example, invited GameDay hosts to join her and university donors for dinner at her home, Jones said. Rece Davis and Desmond Howard stopped by — it isn’t every week that a university president or chancellor invites you to their personal residence.

And the fans provide unparalleled energy — they greet the GameDay bus, camp out overnight, and buy up the entire local supply of posters for the weekly poster-making contest.

When students and faculty members walked by the set, they made sure to stop and welcome ESPN employees. “For this group that travels every week,” Gallagher said, “that warms their soul.”