The video starts with a tight camera shot on toes wrapping around a Ping-Pong ball. “What’s this?” kicks in the trendy TikTok sound bite. Then, the camera cuts to the full-body shot of the athlete without arms. Table tennis paddle in his mouth, he flips the ball up from the ground and hits it cleanly over the net. “O.K., I like it, Picasso,” chimes in the audio as the rally continues.

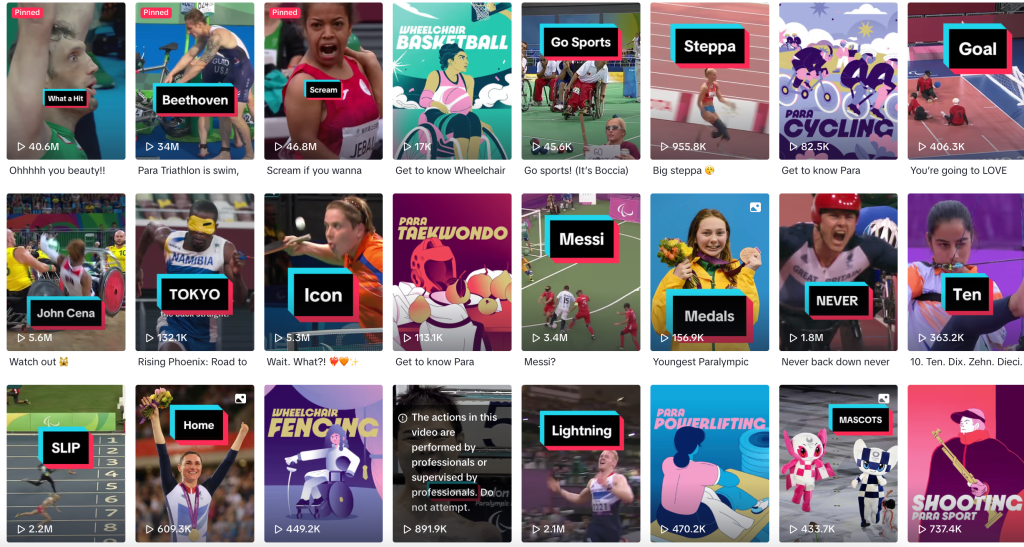

The clip already has more than 10 million views, and it’s easy to construe it as making light of the athlete. Many people do. But the team behind the official Paralympic TikTok account wants you to think about it differently.

“It is O.K. to have a laugh with a person with a disability,” Craig Spence, the International Paralympic Committee’s chief brand and communications officer, tells Front Office Sports. “Now, we laugh with them; we don’t laugh at them. There’s a real key distinction between that.”

The official TikTok account for the IPC has upward of 4.5 million followers. That’s more than major sports leagues including the NHL and WNBA, the viral 76ers rookie Jared McCain, and every major professional U.S. sports team outside of the Kansas City Chiefs and Golden State Warriors.

The Paris Olympics were a ratings success, with surging viewership on NBC, a robust offering on Peacock, and constant viral moments on social media. The Paralympics, which begin Aug. 29, will get a boost from being fully aired on Peacock; getting its own Gold Zone and multiview, both of which made a splash at this year’s Olympics and propelled ratings; and will be broadcast in a record number of countries, with all 22 sports being shown live in some capacity for the first time. But TikTok will also be a key part of bringing more exposure to the Paralympic Games.

Social media was a major engine of Olympics hype that enabled it to reach a broader audience than cable viewers alone. Now, the Paralympics and individual athletes are also poised to take the Games in a new direction with an army of younger, internet-savvy fans.

The IPC is active across social media platforms, but TikTok is by far the most successful. To appeal to a younger generation of sports fans, TikTok is more “entertaining, informative, fun, quirky, and engaging” than the other platforms, says Spence, who oversees the organization’s social media channels. (The wizard behind the account is a Paralympian to whom Spence would refer to only as “TikTokTony.”)

“I think the recipe for success for us has been: All our posts, we want to show great sport. … You will see matters or incidents that are unique to Paralympic sport, which you won’t be able to see in able-bodied sport,” Spence continues. “And then like any other sport, we showcase when things go wrong.”

His team’s strategy is working, as the account routinely racks up videos with millions of likes each. The most successful clips often show mishaps, or lean into popular trends, oftentimes audio clips, circulating on the app. Bite-sized highlights take up most of the real estate on its feed, which is also peppered with educational paralympic sport explainers.

Spence says he’s already seeing evidence that the IPC’s strategy is stoking a new type of fandom. “What has really pleased me in recent weeks is the number of people who have commented … saying, “I never knew this about the Paralympics. I’m going to be watching the Paralympics this time.”

The relationship is mutually beneficial. The social platform announced a partnership with the IPC on Thursday that will utilize TikTok Live for Paralympics content at the opening and closing ceremonies, venue tours, and interviews with athletes, their loved ones, and fans. There’s also a financial component in which viewers can pay for “exclusive gifts” while watching the livestreams of the official account or other creators. For every “Phryge gift” (named after the French hat that inspired the Paris Games’ red mascot) that fans send, TikTok says it will donate to the IPC’s sport development programs.

The opportunity is more perfectly timed than ever, with an audience hungry to vacuum up anything online. Internet culture writer Kate Lindsay tells FOS she mainly consumed the Olympics through social media, and the first content she saw leading up to Paris came from the Paralympics account.

She credits both the Olympic athletes and official accounts like Peacock for being more “social media native” (think, the “Muffin Man” Norwegian swimmer, gymnast Suni Lee spoofing the “unfortunately I wasn’t selected for the Olympics trend,” athletes’ commentary on dating in the Olympic Village, and just about everything from rugby player Ilona Maher).

Lindsay says the Paralympics TikTok is already seizing attention with its quippy, internet-savvy tone—one that Peacock’s own account matched during the Olympics. “I think [the strategy] was a good idea, because it would also be really bizarre in a different way if Peacock’s account was so cheeky and funny about the able-bodied athletes, but then the Paralympics didn’t get to have that kind of fun,” she says. “But it’s all one party—we’re all having fun.” Lindsay says excluding Paralympics from levity online is another form of “othering.”

The Paralympics TikTok came under intense scrutiny in April 2023, largely from nondisabled people, claiming the account was disrespectful and mocking the athletes. Many took offense to its tone, especially in funnier videos using viral, silly sounds. One of the videos that was the target of backlash showed blind triathlete Brad Snyder feeling around for his bike, with an audio of classical music, comparing his motion to playing air piano. Snyder reposted the videos on his channel and has publicly praised the account’s approach.

“The feedback overwhelmingly from Paralympians is they love this account, they realize it’s engaging, our athletes have great senses of humor,” Spence says, who acknowledges the posts must strike a balance, but it will never please everyone. “I’ll listen more to our athletes, and whether they’re offended or not, than people elsewhere.”

Hunter Woodhall, a Paralympic 100- and 400-meter sprinter says it can be “challenging” to find the best way to show Paralympic sports online, but gives the IPC account his stamp of approval.

“At the end of the day, they’re doing exactly what they’re supposed to be doing, which is building awareness of Paralympic sport,” Woodhall says. “Sometimes, no matter how you do it, if you can get people to put eyes on the sport, or put eyes on what people are doing, that’s when you have the ability to change things and make things better for the athletes, for the sport.”

About 16% of the world’s population—an estimated 1.3 billion people—live with either mental or physical disabilities, according to the World Health Organization. By placing disabled athletes front and center, Woodhall says both the live events and the social media accounts “challenge the stigma that is attached to disability” with the goal of creating more opportunities for the world’s disabled population.

That opportunity could even mean sending new athletes to the Paralympics. Spence says he knows a “number of athletes” who started playing sports for disabled people because they saw it on a Paralympics social channel.

The same goes for the athletes’ own accounts. Woodhall boasts 3.2 million followers on his own TikTok account, and an additional 235,000 and counting on his shared account with his wife, Olympic gold medal long jumper Tara Davis-Woodhall. He tells FOS that another runner told him at nationals that he started running because of Woodhall’s videos.

“I think that is the magic, that anybody can watch the stuff that we’re doing and say, ‘Hey, I can do that, too,’” Woodhall says. “If I just keep being myself, then people will understand that they can do the same and be themselves, and not feel bad about it.”

He adds social media has “100 percent” helped more people become aware of sports for people with disabilities, and realize it’s not just a “charity thing.” He and Davis-Woodhall have already had one viral moment in Paris, when the Olympian jumped into her husband’s arms celebrating her victory. It became especially widespread among Taylor Swift fans when it was set to her song “The Alchemy,” which features lyrics about a couple celebrating a sports win.

Alongside Woodhall’s success, Anastasia Pagonis, a blind swimmer, has 2.5 million followers; Jessica Long, an amputee swimmer, has 1.3 million followers; and Nick Mayhugh, a sprinter with cerebral palsy, has more than 850,000 followers. Combined with the Paralympics’ account’s success, “there’s no way that anybody could say that that doesn’t have a positive impact on awareness of the sport,” Woodhall says.

Culture writer Lindsay tells FOS, “I feel like [the account] is breaking a kind of unexpected stigma that people don’t think about, in a good way, and just being successful online, like speaking the online language and showing that you can do that, even if your circumstances and bodies are different. Everyone has a place to be fun and cheeky online.”